| Report Type | Full |

| Peak(s) |

Longs Peak - 14,259 feet |

| Date Posted | 07/26/2024 |

| Date Climbed | 07/27/2014 |

| Author | HikesInGeologicTime |

| The Long White Whale, Part I |

|---|

|

This is once again the script I used for the latest episode of my podcast, which you can find here (or use the RSS feed to search on your preferred service: https://anchor.fm/s/f380746c/podcast/rss). This particular episode is the driving force behind the start date of said podcast; I wanted to time it so I would have an excuse to release this one on what I realized as I started writing and recording would be the tenth anniversary of The Incident, a.k.a. Baby's First Search and Rescue Encounter, whose first part is detailed below. There aren't as many pictures on this write-up as I've tried to put in others in order to break up the Wall o' Text; I still have enough weird feelings about these events ten years later that I find it difficult to insert pictorial comic-relief breaks to supplement the legitimately relevant photos, so hopefully the story itself will feel as compelling to read as it apparently was to write...suffice to say I usually write maybe 2-3000 words in a single day; both parts totaled nearly 20,000 and took me only four or five days in total for the first drafts. Before I pick up where I left off getting ready to leave Denver to start climbing Longs Peak on July 27th, 2014, I would first like to indulge in some surely no-longer-unexpected rambling so that I can give my father proper credit for getting me into fourteeners. No, I do not necessarily mean my first trip all the way up a fourteener that I remember in all-too-vivid detail for the summit and descent parts of Mt. Bierstadt, nor even the attempt a year before that of Pikes, although those certainly helped to seal my fate. I mean that I think Dad might have set me up for a mountain disaster of my own with his choice in listening material when I was a youth learning to ski or visiting friends with him in nearby states to go on hiking and kayaking trips with them. My paternal unit, as the only one of the two of us who was able to own a car and drive it to those locations varying distances from Denver in the years before I had so much as a learner’s permit, had final say as to what played through the car’s speakers to keep the mental pathways stimulated and, by extension, also keep the car on the road. Eventually, however, even he got sick of my whining about the audio version of the medical journals he subscribed to that were apparently slightly easier for him to digest without falling asleep two sentences in than the printed versions (though I loudly dissented on whether either version was nonconducive to naptime) and decided to invest in more stimulating material, like books - real books - on tape. Yes, tape, as in audiocassettes, and those of you reading or listening yourselves who were born in a year starting with a 2 instead of a 1 can ask your parents for more information on how exactly all that worked just as soon as you get off mah lawn! I, after all, have the contents of those books to discuss. I can’t remember whether it was the first we listened to or simply near the beginning, but Into Thin Air, Jon Krakauer’s bestselling account of the disastrous 1996 climbing season on Mount Everest, made an impression on both Dad and me. I believe it wasn’t too long after that that Dad got a copy of Anatoli Boukreev’s The Climb, the Kazakh mountaineer’s response of sorts to Krakauer and an account of his own about the same tragic timeframe on Everest. The wilderness disaster pr0n, as I would come to think of this genre of nonfiction in a way that almost certainly dates me, was not limited to Everest or mountains, although I do recall us also listening to a detailed speculation on whether or not George Mallory and Andrew Irvine might have summited Everest before their demise on the same mountain nearly thirty years before Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay’s famous confirmed summit. Expansion of topics was inevitable, however. My father worked with the U.S. Antarctic program for many years, and his once- or twice-a-year visits to the southernmost continent naturally spurred his curiosity in the history of its exploration. Amundsen, Scott, and Shackleton were thus names familiar to me before I started high school and, of obviously greater significance in the line of my personal accomplishments, before I’d summited anything myself. As the polar explorers and aspirants were more my dad’s area of interest, and also as I grew into adolescence and therefore decided I was Way Too Cool to have anything at all to do with my parents, it was the mountain stories that left the greatest impression on me. Not that I was going to do anything with that impression for some time, as I did evidently need to start my sputtering launch into adulthood in the hardly-mountainous-to-someone-who’s-grown-up-in-the-Rockies East Coast, and even once I did embrace the wealth of potential mountain disasters of my own in the making on school breaks and then after moving back home, they were hardly the sorts of catastrophes worthy of Krakauer or Boukreev’s ranks. Not Another Teen Movie or any dreadful early-aughts teen comedies, perhaps, given my father’s intervention in my attempt to create a rom with no vom…er, com on Bierstadt’s summit, but even on the more-literally-down-to-Earth level of Cheryl Strayed’s Wild or Bill Bryson’s A Walk in the Woods about those authors’ respective journeys on the Pacific Crest Trail and Appalachian Trail, they still were not.

Which of course I was okay with! Naturally, as an English major who had been praised for my writing abilities from high school all the way through my Master’s program, I had ambitions for a bestseller of my own one day. It would be the next Great American Novel, though, a work of fiction, if I had anything to say about it. It would certainly not be a work of art in the wilderness disaster genre that I had come to enjoy as a child and absolutely not one centered on a well-trafficked mountain in a popular national park. Or so I’m sure I kept insisting to myself as I drove Jimmy and myself to Rocky Mountain National Park, regularly placing in polls as the fourth or fifth most popular in the U.S., around 1 a.m. exactly ten years ago so we could contribute to the traffic on its high point, Longs Peak. I can no longer remember whether I’d told my high school best friend about how the last line of Don McLean’s “American Pie” had blasted through the speakers of the car I was now well old enough to own and drive when I’d gone to pull said car out of my parking lot so Jimmy’s car could occupy my space instead of sitting out on one of the busy streets in my neighborhood all day, for we both knew that the outing would take literally all day. The tension was palpable even without McLean’s voice lingering on the last word of the song, the verb form of death, in my ears. Jimmy, despite having warmed up to the idea of a repeat journey for himself up Longs so that he could bear witness as I too experienced its wonder at last, had seemed to me to have second thoughts ever since we’d set the date of the last Sunday in July. Not easing the tension in any way was the mysterious dead battery that had somehow afflicted the brand-new loaner car Jimmy had received from the dealership to which he’d taken his own mysteriously afflicted new vehicle, a problem so all-consuming he could apparently neither enlist the help of AAA to give him a jump nor text me to tell me of his latest woes, thus putting us on the road two hours behind our set start time. Very mysterious, indeed. Further not helping the mood was the mugginess of the air surrounding us as I turned off US-36 in the town of Lyons north of Boulder and onto State Highway 7, then steered back and forth up the winding curves that would take us to the main Longs Peak Trailhead. Oh sure, Colorado weather is a force unto itself, one to which numerous adjectives can be applied and many of them four letters in length, but “muggy” is rarely one of them in a state whose semi-arid climate compels experienced hikers to warn newcomers about the dangers of ankle-swiping cacti along trails in the high plains and foothills. Even further not helping was Jimmy’s restlessness with what was playing on the radio. I was already irritated with him over the delay that he’d made no attempt to update me on while it was happening, so I felt it necessary to restrain myself from snapping that the driver and car owner does have final say in listening material lest my temper get the better of me. I might have relaxed when he finished pressing all my preset buttons and resettled in his seat if I hadn’t had a good idea why he was doing so. One radio station played The Doors’ “Light My Fire,” another Led Zeppelin’s “Kashmir,” and a third Pink Floyd’s “Hey You.” “The bands,” Jimmy exhaled. “Three of them, all playing at the same time, just like the first time I saw Longs.” Part of me wanted to roll my eyes and make a sarcastic remark about his superstitious nature. He and I had listened to a lot of those three bands, plus another classic rock group or two, in the past couple years, and I knew he’d gotten into them because of how much of an impression their music had made on him when he’d taken hours-long drives around the northern part of the state as a college student and fledgling member of the working world, inspired to write poems by the stillness of the night as well as the views of the mountains, Longs naturally standing out, when first light hit them. Classic rock, or the bands my parents had almost certainly listened to during their own college days, had been my own preferred taste in music literally as far back as I could remember, so I’d been eager to encourage Jimmy in his appreciation of these musicians while deepening my own familiarity with them in the process. But they’d since taken on a superstitious significance for me as well, given my then-bestie’s insistence on connecting them with Longs, a peak that had taken on an obsessive significance in my own head after nearly two years of being foiled by it. Even though the rational part of my brain knew it was just a coincidence, then, I couldn’t convince myself it was mere happenstance, nor would I be able to persuade Jimmy of such even if I thought I could. I pressed the radio preset button myself to stick with “Light My Fire.” I’m sure I did my damnedest to ignore the increased turbulence in my stomach as I kept twisting the steering wheel back and forth, higher and higher on the winding road through the visible dampness. Perhaps one or the other of us faux-cheerily pointed out that at least I hadn’t gotten pulled over on this drive up to the trailhead the way I had before last time’s attempt, not that I could find much of a positive in anything, even the lack of police intervention. This occasion may well have been the start of me telling myself that I’d feel better once Jimmy and I changed out of our comfier footwear into stiffer hiking boots and put said boots to trail, that the act of hiking up the gratingly steep first half-mile to the Eugenia Mine Trail Junction would be enough to quiet the doubts still swirling in my mind, vocalized there in a mixture of my dad’s voice and my own, about how Longs didn’t have Everest’s fatality rate but did nevertheless have a reputation all its own.

My unease grew when my then-friend and I broke above the forest and paused to look out toward the lights of Boulder before beginning the tedious stretch of the next 1.5 miles leading up to Chasm Lake Junction. The last time we had been up here together, on the day of Jimmy’s successful attempt and my failure, the nearby city glittered so distinctly that it may as well have been a bejeweled cross-stitch laid out on black velvet by an expert in the craft. On this night, there were lights…or rather, light. All the individual points of illumination had blurred together in an indistinct orange haze, the warmth of the color belying the clamminess - another descriptor hardly befitting often-drought-plagued Colorado - that we hadn’t managed to leave behind when we’d escaped the trees. Jimmy or maybe even I may have made a comment about the more distinctive string of white lights from other hikers’ headlamps bobbing up the trail behind us, though I can’t imagine I deigned to linger any longer than was absolutely necessary. Adding still more to the tally of unhelpfulness was Jimmy’s insistence as we clambered up toward Chasm Lake that we were making great time, really! In his defense, however, I think there truly was very little that I would have deemed overtly helpful at that point, short of finding a hidden teleporter that would beam us directly to the summit, and even then, I remembered the feeling I’d had on my first summit of Blue Sky that I’d cheated by getting a ride down, so skipping the physical torment of the standard ascent route would clearly invalidate my long-awaited checkmark of this miserable mountain. Perhaps some kind of grand cosmic stopwatch with a pause button we could hit while we scooted up the trail to the best of our ability until I was satisfied at last that we’d made up for the hours I’d spent waiting to see or hear from Jimmy…? But alas, all I found to try to assuage my lingering willies was the speaker on my phone, which I now cringe to remember using to share Led Zeppelin’s Physical Graffiti with Jimmy as well as every other hiker within earshot, not to mention any diurnal wildlife trying to catch some much-needed shuteye. The one hiker who blew past us near Chasm Lake Junction with an enthusiastic, “Awww yeah, sweet music!” notwithstanding, I send my sincerest apologies out to anyone else on the trail that night needlessly disturbed by my past-self’s idiocy. Jimmy, who hadn’t been nicknamed Tiny Tank by our high school friend group for nothing, definitely visited the outhouse at Chasm Lake Junction, and perhaps I did as well. Maybe I snarled at him yet again before he could repeat his insistence that we were doing great on time, really, as we set off, still in the dark, for our next major trail junction: Granite Pass, where the East Longs Peak Trail that we were on met the longer and therefore less traveled North Longs Peak Trail coming in from Glacier Gorge, farther north, naturally, in the Park.

This stretch may finally have allowed me to let my guard down a little, perhaps believe in Jimmy’s fervent insistence that he may have even started to believe by then that everything was going to be okay, really. It is, after all, where the sharpness of the grade for the first 3.5 miles - half of the total one-way distance - levels out some, so Jimmy and I could engage in some light conversation without needing to wheeze for air every three steps or so. I may even have regained a bit more confidence in my abilities as the sun started to send feeler rays over the horizon while we approached Granite Pass, despite the fact that I’d hoped to be a whole mile ahead and above on the Keyhole that unofficially separates the hiking portion of the route from the scrambling portion when first light hit. Sunlight does soothe the lizard brain, however, and in this case, it seemed as if the mere threat of its presence caused the lingering fog to start breaking up and scattering. Still, on hitting and then climbing above the pass as the sun did the same, I found myself disappointed but not utterly surprised when a keening electronic shriek battered our ears. I may have taken a step or two in annoyance - surely this couldn’t be happening, not now! - then grabbed the controller for my insulin pump out of my pocket to confirm what my beleaguered eardrums already knew: the pump had gone offline, dead of apparent altitude sickness. A brief pause in the action here to address the potential record scratch for those who haven’t had the questionable privilege of hiking with me or reading some of my other trip reports: yes, I am a Type I diabetic. No, this was not a new development as of Longs Peak or shortly before; in fact, by that point, I had been dealing with my nonfunctioning islet cells for over a quarter of a century. I simply opted to focus prior wordy-enough write-ups of prior fourteeners on the elements I deemed more important as well as interesting to discuss. For the most part, I deem my medical conditions to be unworthy of discussion except beyond a basic, “If I say I need to stop to do something about my blood sugar, I really mean it,” to my hiking partners. I’d been handling it without significant incident for long enough, and unless a given hiking partner is an endocrinologist or medical researcher looking to recruit patients for a trial run of a potential cure, it’s not something I like to talk or think about more than is absolutely necessary for survival purposes. This particular diabetic incident, however, was and is worthy of discussion, as it would turn out to be the domino that set the near-collapse of my survival in motion, a possibility Jimmy was surely aware of as I went through a rigmarole I was well used to by now to shut the damnably finicky piece of equipment up. I did have more insulin as well as replacement of the parts I’d need to get the pump running again…back at home. There was a reason why it was in Denver instead of with me. All that medication and equipment was expensive, and I’d feared what might happen if I’d had it in a backpack that took a tumble off one of the nauseatingly high cliffs the route along this mountain’s backside skipped over and across. I knew I wouldn’t be able to refill my insulin prescription for another ten days, so if something happened to what was left of the vial in my fridge, I would not have been surprised if my insurance deemed an early refill to be an unnecessary expenditure on their behalf. I can’t remember how much, if any, of this I explained to Jimmy after I finally silenced the pump’s piercing wail. All he knew was that a lack of insulin surely meant trouble, and that in turn meant that we were surely turning around. Maybe I gave whatever words he had to say about the matter some thought as I stared at Longs, its summit alight with the rising sun, above a partial view of its sheer East Face, also known as the Diamond, and damn did it ever shine like one all ablaze in alpenglow.

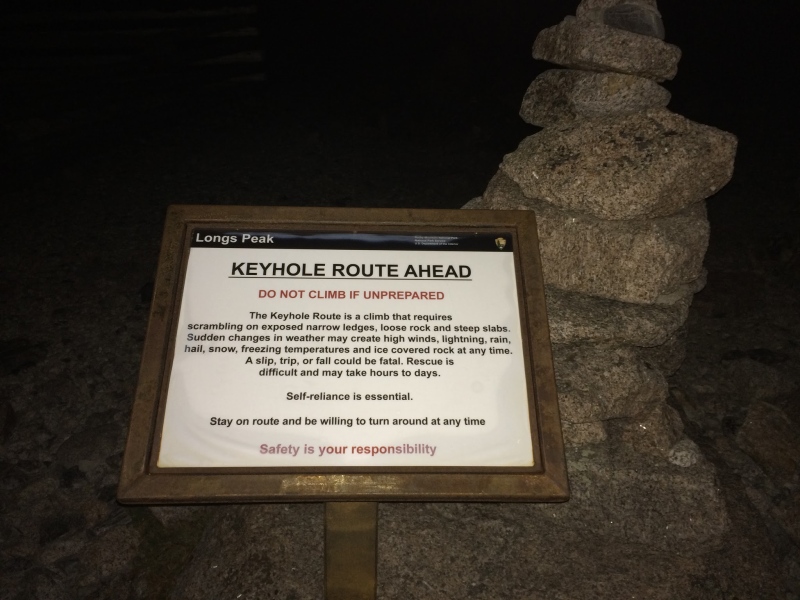

I put the pump controller back in my pocket and adjusted my backpack. “I’m going on,” I told Jimmy. I don’t remember whether he verbalized his incredulity or simply let a blank stare speak for itself. I pointed at the summit. “It’s right there,” I insisted, then gestured toward the pocket that held my completely-shut-off insulin pump. “I turn this thing off all the time so I don’t have to stop and deal with hypoglycemia every five minutes while I’m hiking. Granted, I usually turn it back on sometime on the way down, so I’m sure I’ll be feeling a little groggy by the time we get back, but…” I gestured again at the summit. “I already got turned around on this mountain once. I’m not bailing again.” I don’t think Jimmy said very much as we continued up the now-united Longs Peak Trail to where it ended at the start of the Boulderfield, where the National Park Service has put up a sign warning of the dangers ahead: “KEYHOLE ROUTE AHEAD,” it warns in all caps. “DO NOT CLIMB IF UNPREPARED.” It then goes on to list many of the dangers, including that of the varying rock quality and potential weather hazards, before cautioning that, “Rescue is difficult and may take hours to days. Self-reliance is essential.”

I’m not one to shy away from a little tasteless gallows humor, but I think on that day, I simply side-eyed the sign and braced myself to begin boulder-hopping without making any comment about the severity of its words. The Park makes neither its warning signs nor its naming choices whimsically, after all, and so the Boulderfield is exactly as described: a long, arguably tedious series of stepping from the top of one boulder to the next, most of it flat until the cairns presumably placed by NPS wind hikers southwest and up along the flanks of Storm Peak B, the 13,000’ mountain that shares a ridge with Longs. The route then steepens sharply as it turns more stair-steppy, then finally demands hikers - ones of short stature and meager balance, anyway - begin using all fours to heave themselves up to the feature serving as Longs’ jagged saddle with Storm as well as gateway to the mightier mountain’s summit: the Keyhole. At least some of the remainder of the ascent will bear some resemblance to my earliest fourteener experiences. For instance, I don’t remember many details about reaching the Keyhole on that particular day - most of what I do remember is cobbled together from memories of subsequent visits. I presume it was windy, because it’s rare for there not to be winds blowing in from the west, and the Keyhole’s ridge does separate the eastern side of the route we’d come from from the western side we could now see more of…not that I remember much of that view, either. I also don’t remember the beginning of our scramble across the Ledges, the aptly-named-as-all-else series of rock shelves breaking up the otherwise grimly steep slopes between the Keyhole Ridge and a sharp tumble into Glacier Gorge below. I can’t even remember whether Jimmy took the lead, seeing as how he’d done the entirety of the route before, or whether I insisted on being the first to play connect-the-bullseyes, as lacking adequate room to build lasting cairns, Rocky Mountain National Park paints yellow targets surrounded by red circles to help guide climbers who might otherwise wander off route into exactly the sort of situation the sign staked out at the upper end of the designated trail warns about. The Trough, the next distinct section of Longs’ backside, does come through a little more clearly, and as is the case when part of an ascent from ten years or more ago does have some semblance of clarity, that means I have few nice things to say about it. The painted bullseyes continue up this 600’ of steep gully even though the route leaves little to the imagination; the top of this gully is visible from nearly all of it. And therein lies the despair! The gully’s steepness required someone of my aforementioned meager stature and balance, anyway, to use a hand or two for upward motion about once every three or four moves, if not more, and the need to gasp for air every five moves or so usually brought with it a desperate glance upward for some confirmation that the end of the misery was near. Alas, every glance seemed to show the exit coming no closer - in fact, on several occasions, I seem to recall my very own version of a promised land appearing even farther away than the last time I had checked. But just as all good things must eventually meet their ends, so too must all bad things. It only seemed like forever but was perhaps only an hour before Jimmy and I stood and frowned at our next nemesis: a seam in a polished slab of granite maybe ten feet high where Longs joins the series of fang-like formations called the Keyboard of the Winds.

Or maybe it was more like Jimmy was staring in awed despair at the seeming featurelessness of the stone before us while I glared at him. “You must have gotten past this somehow the last time you were up here,” I insisted while he presumably tried to remember how exactly he had managed it. A pair of climbers who’d played leapfrog with us up the second half of the Trough, passing us when we paused to groan and gasp for air and vice versa, had caught up to us once again and caught their breath while we examined this stonefaced stone face for answers it wasn’t giving about how to get it to grant us passage. Finally, their respiration and heart rates restored to normal, they were eager to continue onward and upward. Maybe they asked permission, maybe it was understood that we were glad to accept their help when they grabbed each of us in turn by our waists and hoisted us up high enough for us to find some good handholds up top that we could use to pull ourselves the rest of the way up to the ledge in front of the Chockstone, the awkwardly placed boulder guarding entrance to the Narrows. Herein lies the test of tests for those suffering from acrophobia. The foot-wide at the still-aptly-named narrowest band marking the one break in an otherwise harrowing cliff face is walkable, but a quick glance off to the southern side, overlooking a whole lot of nothing between its edge and the next solid landing a couple thousand vertical feet below, could be enough to have one collapsing into a fetal position, hopefully a reasonable distance from that always-too-close-for-comfort edge. And here at the narrowest end of it, with our backs slouched against the first fang jutting out to the Keyboard so that we could allow enough passage for the two guys who had given us the boost to magic their own way up and pass us for good, Jimmy’s face paled as beads of sweat dampened his forehead despite the crispness of the breezy morning air. “I can’t do it,” he said. There seemed to be no point in reminding him that he obviously could do it because he had done it before. I took another look at where our impatient heroes were already most of the way across the short but severe crossing. I wasn’t loving it myself, but if I wasn’t going to bail at Granite Pass for a broken insulin pump, there was no way I was going to bail less than 300 vertical feet from the summit I’d spent so much time obsessing over. I said as much to Jimmy, promising I wouldn’t leave him waiting for too long, then found a solid set of handholds on either side of the badly-placed boulder. An equally solid set of footholds later, I was on the Narrows. It’s a testament, perhaps, to mind over matter that I don’t remember that crossing on the way to the summit. My next semi-clear memory was after hauling myself up a chest-high block and staring at last up at the Homestretch, the last 250 vertical feet of the route, but the steepest that climbers need to go up rather than across. But I would not be going up alone. I no longer remember whether there was a tap on my shoulder or a smug greeting or if I simply happened to glance to my left to see if I needed to let someone faster start climbing ahead of me, but whatever alerted me to his presence, I quickly found myself congratulating Jimmy on having made it across the Narrows after all. “I couldn’t let you finish up alone,” he explained as we leaned forward into the Gollum-esque crouch we’d use to crawl up the highest reaches of rock towering above the rest of Rocky Mountain National Park. I swear I remember Jimmy asserting at some point on our ascent that since I hadn’t had the privilege of summiting before, I should be the first to reach the loftiest prominence of this National Park’s loftiest pile of rock. I would wonder later on whether the effects of the hours-ago halt to the insulin being infused into my body had already set in, though I would conclude even later still that no, I just really really REALLY suck at climbing anything really really REALLY steep. As Longs was my first really really REALLY steep mountain, however, I had no good explanation at the time for why I had to huff and puff and gasp and wheeze as I pulled myself up to and then into the short chute that marked the top-out of the most forgiving path to the summit and stumbled onto the football field-sized sprawl of boulders worn over millennia by the elements to the one sequence of formations thrusting most defiantly above the rest, the uppermost bearing the U.S. Geologic Survey marker…where Jimmy waited for me, perhaps already taking a bite out of his sandwich. I got him to pause whatever he was doing for a moment to take my Longs-awaited summit victory pictures, ones that I thankfully have saved in a few locations as I once again have a surprising lack of recollection about actually spending what little time I did on the summit. The timestamp from those pics reads 10:48 A.M., way later than I’d hoped for when I’d set a meetup at my place for 12 hours and 18 minutes prior, and the pictures of me with a toothy grin, a thumbs-up, and a handmade cardboard summit sign like every other fourteener newbie in existence in the other hand have a disturbing backdrop of clouds boiling toward the peak.

I decided to dig into my own lunch despite knowing that my blood sugar didn’t need the extra boost. The rest of me needed the calories and the respite, never mind Jimmy glancing nervously at those clouds strengthening nowhere near far enough away and urging me to get a move on. I can no longer recall whether I pointed out to him that we might have been able to take more time and enjoy ourselves if we’d left Denver when I’d wanted to, but regardless, it was quite obvious that he was correct about us needing to head back down. And so I packed away what remained of lunch, chugged the rest of my second of the four liters of water I’d lugged up the mountain as well as much of the third - that ascent had been dehydrating work - and then re-shouldered my pack to trudge to the edge of the summit. Jimmy once again blanched at the sight that awaited us below the summit’s lip. The Homestretch sure did look more perilous from the top than from the bottom; that this was the segment of the backside steep and subtle enough on holds to give the Keyhole route its Class 3 rating on a scale that goes from 1-5 was not lost on me at that moment. Still, now that I was prepped and ready to get the eff off this mountain, this was no time to dilly-dally. I sat down at the edge, my hands stretched out on either side of me, reminiscent of bracing myself to go down the Big Slide at some playground or another as a child. “Sit behind me and stay close,” I told Jimmy, who was now visibly as well as audibly hyperventilating. As soon as he scooted into position behind me, I took a quick glance downward to make sure no one was in our direct line of fire, then pushed off. I would in no way, shape, or form recommend the tandem snow-free glissade in just about any situation in which it can be avoided. Not only was it a faster way of descending the steep slabs than I really would have preferred, despite the stiff upper lip I’d set at the top and maintained in order to project a shield of confidence that I hoped would envelop both my friend and me, it also turned out to be hell on my bottom outerwear, my long underwear, and my regular underwear. Suffice to say that I would not be entirely surprised if tiny fragments of Longs Peak turn up in the eventual results of my first colonoscopy. As I didn’t know about techniques more conducive to preservation of self, clothing, and dignity while descending Class 3 rock at that time, however, I would rate this method a solid C-minus; it did deposit us at the base of the Homestretch with only surface-level damage, so it passed the test, if barely. After taking a few deep breaths, we got to our feet only somewhat unsteadily, brushed what was left of the backs of our pants off, and prepared to return across the Narrows. I do remember crossing it back to the Chockstone; it seemed much longer that way than it had the other, and I said as much to Jimmy. “And why are we going back up?” I somehow managed to whine breathily of the mild grade that drew us back up to the top of the Trough. Jimmy murmured something in commiseration before we grumbled our way around the Chockstone and stared down the slick, seemingly near-vertical obstacle that the duo doubtlessly already halfway back to the trailhead by now had tossed us up earlier. I’m not entirely sure how Jimmy navigated the sketchy-from-all-angles descent of it; I just remember him already standing at its base, arms crossed in irritation, as I finally tossed my backpack down clear of him to butt-scoot along an uncomfortably narrow ledge level with the top of the obstruction, then hesitated at its outer edge, one foot hovering several inches above the next available hold down and my hand extended as far out as it would go and still a few inches short of the next available handhold out. It was no small measure of relief that I survived the necessary leap of faith with further injury only to the remnants of my dignity. I may have turned to Jimmy with a grin, the confidence that had been fluctuating all day hitting a brief high at last after having successfully navigated what sure seemed like the crux move. “Let’s get out of here,” I might have said as I started picking a way down the Trough. But good grief, the Trough is tedious. Just as we never seemed any closer to the top on the way up, we never seemed any closer to our re-entry to the Ledges on the way down. Step, step, grab for balancing handhold, bigger step, rinse, repeat, over and over and over, with the only break in the growing dismay that we’d stepped into some kind of variant on Sisyphus’ eternal punishment occuring when I looked down in reflexive agony to see if we were even the slightest bit closer to the next circle of Hell…and saw that the clouds that had been politely waiting on the other side of the mountain had now flooded onto our side of it and that the top of the latest fogline was high enough to obscure our exit. Jimmy and I both watched the fog swirling too close for comfort below us with grim fascination, spellbound until the winds that are an alternate foe or friend of fourteener fans drew it far enough away from our route to permit us to scrabble for the beginning of the Ledges, finally within reasonable-looking distance, with renewed vigor. It’s once again a credit to the probable ease of passage that I don’t remember returning over the Ledges any better than I remember having forded them hours before, nor do I remember stumbling back through the Keyhole despite having a taken a picture of it nearly four hours after my last summit picture was taken, according to my timestamps - hardly a candidate for a Fastest Known Time at that glacial pace!

I’m also no longer sure whose idea it was for us to succumb to the relief of having reached the point of increasingly likely return by taking a break in the Agnes Vaille Shelter just below and off to the side of the Keyhole. Despite the fact that its namesake, an accomplished mountain climber in the early twentieth century who had met her end from hypothermia and exhaustion following a winter ascent of Longs, had perished on a different part of the mountain, the shelter stands where it can serve the greatest need to the most visitors to come up that high. And was I ever in need! I had never spent that much time using my hands as well as my feet since, I imagine, before I learned to walk. This mountain had marked my introduction to Class 3 climbing; while I’d been rock-climbing a time or two before, those sessions had been roped and on much shorter routes with no need to hike six miles up several thousand vertical feet to reach them. Longs Peak marked the most strenuous outing I had experienced in my life up to that point. The stone benches and windbreaking walls of the Agnes Vaille Shelter were not just welcome, I deemed, but absolutely necessary to reinvigorate my pained and shaking legs. Of course it could hardly escape my notice that my weak-by-even-fourteener-descent-standards condition might have something to do with the nine or so hours since my insulin pump had broken down. If this were a normal fourteener, one on which I’d decided to turn the pump off myself, I absolutely would have turned it back on by now, seeing as how going downhill, while certainly no casual saunter to go by the Trough having been an equally large pain in the everything both directions, generally reduced demand on the body’s energy levels. A personal record for high blood sugar would certainly explain why I had already downed ¾ of my water supply - a supply 1-2 liters higher than I typically carried on a fourteener, because I’d thought it best to come prepared in that regard at least - and was now draining my last water bottle in the shelter. Excessive thirst is a well-documented symptom of hyperglycemia, after all, and the despair I felt at my still-dry mouth after I’d shaken the last drop out of that last liter marked the realization that the allegedly easy part of our return to my car six miles away was going to be easy in a highly relative sense. My legs, far from feeling rested and refreshed, certainly didn’t feel any better about the stairstep-esque maneuvers required to descend the sloped part of the boulderfield. I had no objections to stopping for a photoshoot when Jimmy took a full-on gawk at a summit that was now all but shrouded in clouds; the renewed ominousness of the mountain was worth documenting, and anyway, I hardly felt hyperbolic in being convinced that my legs were dying.

Jimmy likely had to keep pausing every few steps to wait for me and/or croon encouragement, even once sharing some of his own dwindling water supply, as I minced through the rest of the flatter boulders that should have proven less of an obstacle between us and the honest-to-goodness trail. I hoped the comparative smoothness of said trail would provide some measure of respite to my agonized quads, yet Jimmy, usually the slightly slower of our twosome, still found himself getting ahead and having to pause for me to catch up once we had left Longs’ grim warning sign above and behind us. “I have to sit down,” I groaned as I shuffled up behind him in the latest of a numerous series of stops on my then-friend’s part. I didn’t so much sit down as fall onto a flat-topped boulder marking the edge of the trail. Before Jimmy could glance nervously at a sky cloudier than ever and risk a retort about how different things might have been if we’d started when I wanted to (albeit leaving myself subject to a counter-retort about my own decisions as the day progressed, of course) with an offer of a gentle but urgent suggestion that we make this break a short one, a full-body heave seized me. Whatever came up to besmirch the dirt at my feet was liquid, somewhere between crimson and black in color. Hindsight has me relatively certain that the horror-movie-reminiscent former stomach contents had probably received that worrying tinge from some kind of sugar-free flavoring I’d used in one of my water bottles to entice me into stopping for rehydration more than I would if I knew I only had plain water, but at the time, my own concern quickly faded as I realized I could parlay Jimmy’s admittedly understandable disquiet into extending this break just a little longer, maybe supplementing the ibuprofen I’d already taken somewhere between the Keyhole and here with some Tylenol. My dad had once told me that the two OTC pain relievers could be combined as an emergency measure, and this sure was starting to feel like an emergency. Perhaps it was the united efforts of the popular painkillers, perhaps the mildness of the grade and evenness of the trail between Granite Pass and Chasm Lake Junction, perhaps some combination of both, but while I certainly wasn’t able to emulate the trailrunners who frequently jog past me with nary a ragged breath on fourteeners all across Colorado, I was finally able to move at a more regular clip. Jimmy remarked something to the effect of how much perkier I appeared, and I couldn’t help but agree. Nevertheless, as the Chasm Lake Junction outhouse silhouetted by a leadening sky came into sharper and sharper focus, I knew I wouldn’t be able to pass up an opportunity to flop into a fully-reclined position on a conveniently-angled link of boulders while Jimmy graced that ignoble but necessary building towering above. My then-friend emerged from the restroom and perched on a boulder close to the ones I had melded with, clearly ready to spring up and bolt down the trail the instant I showed any signs of life. But even when he did launch himself back to his feet as soon as the stormclouds coalescing above us sparked a white-hot flash that was almost instantaneously followed by a BOOM which immediately echoed, soundwaves ricocheting off the mountains surrounding us, I simply lay still, unwilling to let anything as piddling as a mere electrical storm ruin the closest I’d come to a peaceful rest all afternoon. So I watched with annoyance as Jimmy dashed a few feet down the trail toward the trees, then stopped and turned to me, his eyes as white around the irises as the blast of electricity that had just graced some patch of ground within a few hundred feet of us, to judge by how closely that thunderclap had rolled out on its heels. He shouted my deadname - this was years before I came out or changed any of my legal documents - surely adding something about, “Come on!” or, “Let’s go!” in a tone, I am certain, probably not too far off the one he used on his dog. I groaned when the second burst of lightning preceded yet another blast of thunder somewhere above me. Did I really have to get up for this? It wasn’t as if any of the ambient electricity was guaranteed to strike me or any of the boulders or the signpost advertising the trails to Chasm Lake and Longs’ summit right near me, after all, and surely this too would pass, as all things must.

Nevertheless, I reluctantly contorted myself into sitting upright after Jimmy reflexively hurtled another few feet down the trail while calling my deadname with increased franticness. “Coming,” I groaned as audibly as I could while readying my trekking poles to bear as much of my body weight as they could. Standing up was going to suck, my tortured thigh muscles informed me. The first pieces of hail started whizzing through the air and pelting my ear and the side of my face as I winced and minced toward where Jimmy was standing, now a bit farther away still. I paused both because of just how loudly my legs were protesting - loudly enough to just about drown out a third none-too-distant flash-BOOM - and also to pull the hood of my rain jacket around my head with little time to spare before the clouds unleashed the full, unfettered, Old Testament-level fury of the hail they contained at us. I heard Jimmy call the name he knew me by a few more times as he began to run down the trail with no fetters of his own. “I’m coming!” I snarled back a few times as well as I could around lungs that seemed to demand as much strength as they had on the uphill portion of this hike in order to work at all, doing less and less to conceal my irritation with each growl as he disappeared from my view. It wasn’t too long before the hail swallowed up any audible traces of him as well. That was just as well, however; I had plenty of remaining targets for my lingering irritation. The legs, for one, which now seemed to be blatantly ignoring the ibuprofen that I had re-upped a few hours before I was really supposed to. The rain jacket, which was not as waterproof as advertised and so was serving less as a repellant and more as a conduit for the hail smacking into me with a constant spitfire rat-a-tat-tat, some pellets bouncing off but more than enough clinging on, being absorbed into the jacket’s material, then spreading their beneficence inward to the shirt covering my increasingly goosefleshed skin. At least the boots seemed to be holding up their end of the bargain to keep as much water as possible out of my socks, which was good, because by my estimates, it had taken all of thirty seconds for the East Longs Peak Trail to turn into the East Longs Peak River. This wasn’t necessarily a bad thing, though. With my vision compromised by needing to squint in order to protect my eyes from the pieces of hail that would zip past my jacket’s hood as well as my glasses, having any sort of indicator, sloshy as it was, that I was still on trail was something of an advantage. This too shall pass, I reminded myself as the pelting, sloshing, and flash-BOOMing raged on, though with the last thankfully seeming to recede somewhat. Storms in Colorado tend not to persist for very long. Fifteen minutes, I promised myself, and this one would move along to go bother Boulder instead of me. While I can’t entirely trust my own perceptions of time by that point, however, it seemed to become increasingly apparent that this was sticking around longer than the average late-afternoon thunderstorm. The lightning and thunder did seem to be subsiding, but the hail appeared to be quite content where it was. For lack of evidence of my then-best friend to yell at, I began taking my frustration out on the sky. “All right, that’s enough,” I hissed out loud at the clouds continuing to lob mini-ice bombs at me. “You’ve had your little fun. I’ve learned my lesson. I should’ve turned around when my insulin pump quit working however many hours ago that was. I get it. You’ve made your point.” Still the hail kept slamming down into and around me. “Seriously. That’s ENOUGH!” I shouted, never mind the convulsions in my lungs and dehydrated throat from the energy unnecessarily expended at this unstoppable force. I can only conclude my physical afflictions must have affected my mental state as well, because after another few minutes went past with no sign of relief from the constant battering of hail, I came to a standstill in the middle of the rushing river-trail, tilted my head back, and screamed, “IF YOU DON’T CUT IT OUT THIS VERY INSTANT, I’M GONNA RETROACTIVELY CIRCUMCISE YOU!” It was not in fact that very instant, but perhaps those clouds had also been raised Jewish and attended or at least heard about a bris or two, because it wasn’t too terribly long after that little outburst that the hail slowed down to merely one whizz-bang every few seconds, then ceased entirely. I could’ve done without the thick fog - more clam chowder than London’s pea soup, in my assessment of the color scheme - that it left in its wake just as I could have done without my throat protesting the unnecessary use I’d made of it by contracting its muscles in a way that caused me to retch, then lose whatever remaining shreds of dignity I might have had to my name when my bladder decided to register its own protests in turn by voiding its contents onto the front of my pants. This in turn made me cranky in a whole new way - if I’d known I had any liquid at all anywhere in my parched system, I would’ve tried to channel the mountain goats ubiquitous at many of Colorado’s loftiest heights, namely their ardent passion for human liquid waste. Desperate times called for desperate measures; if only I could’ve declared carpe pee-em!

I believe two hikers appeared out of the mist, though even in the moment, I was rather fuzzy on whether they were going up or down. Either way, they paused to watch me continue my zombie-like shuffle-flail down the trail. “Are you okay?” one of them asked as I dragged myself within earshot. I seem to recall pausing myself, both out of a desire to give my beyond-aching muscles a brief break from the agony of movement and also to think really, really hard about my condition. But in the end, what could I say, really? Everything that was happening to me was entirely my fault, I was so resistant to going to the hospital that I’d told Jimmy early on in our friendship that he was not to call emergency services under any circumstances whatsoever, no matter what my blood sugar was doing, and even if I did capitulate on this occasion, most likely a significant portion of my current state was due to sheer exhaustion, and if that was the case and I felt substantially better after a hospital-bed nap, I’d only get a lecture about wasting the emergency room staff’s time. So I gave the only answer I could to the hikers hovering in the mist: “Yeah, sure, everything’s fine!” I then lurched back into motion, trying to hide both a grimace as well as my stained pants as I dragged each leg out in front of me with what felt like the sort of effort an ultramarathoner needs to make that last mile to the finish line. Shortly before I descended into the greater cover of the trees, I passed a sign pointing the way to the Battle Mountain Group campsites, 2.5 miles from the trailhead. Chasm Lake Junction was 3.5 miles from the trailhead. I gritted my teeth; had I really traveled but a mere mile through all that seemingly endless chaos? But at least I’d made some progress, and if the clouds decided to regroup for a Round 2 of their Electric Boogaloo, I’d now have the pine trees of what the NPS calls Goblins Forest to protect me. Better still, I could hear a voice - Jimmy’s voice! Calling my deadname and sounding like he was dead ahead! “Jimmy!” I shouted back, all the irritation at him, I’d decided, having been left behind me at Chasm Lake Junction. “I’m here!” I was in too much pain to put too much pep in my step, but knowing that my friend was somewhere nearby, that he must have taken cover under the shelter of the highest of tall pines while waiting for me to catch up, did entice me to shuffle a little faster. The fog wasn’t going anywhere, which meant there was no sun to dry out the chilled clothing compressed to my skin, and at this rate, I was sure that even July’s elongated daylight wouldn’t be enough to prevent us from reaching my car in the dark of night, but none of that mattered. I’d made it this far, and for the rest of the descent, I wouldn’t be alone. Jimmy called my deadname again as I entered the tall trees where I myself would have taken cover had our situations been reversed and painstakingly moved toward a curve in the trail where I figured he had to be, maybe out of a desire to not be under the most attractive-to-lightning pines when the second-most-attractive would do? He sounded so close. “Jimmy!” I called out. “Where are you?” I heard my deadname again as I shuffled toward the bend in the trail. He had to be nearby, absolutely had to be; yes, mountain acoustics are weird, but his voice was too distinct to be coming from any lower on the mountain… I stopped as I came around the bend. “Jimmy?” I could now see a decent way down the next stretch of trail, a stretch straight enough that anyone standing on it or next to it would have been visible for a couple hundred feet. The voice I’d been hearing was so audible, so clear that it had to have been coming from within that range… …if, that is, that voice had existed outside my head. End Part I |

| Comments or Questions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Caution: The information contained in this report may not be accurate and should not be the only resource used in preparation for your climb. Failure to have the necessary experience, physical conditioning, supplies or equipment can result in injury or death. 14ers.com and the author(s) of this report provide no warranties, either express or implied, that the information provided is accurate or reliable. By using the information provided, you agree to indemnify and hold harmless 14ers.com and the report author(s) with respect to any claims and demands against them, including any attorney fees and expenses. Please read the 14ers.com Safety and Disclaimer pages for more information.

Please respect private property: 14ers.com supports the rights of private landowners to determine how and by whom their land will be used. In Colorado, it is your responsibility to determine if land is private and to obtain the appropriate permission before entering the property.