| Report Type | Full |

| Peak(s) |

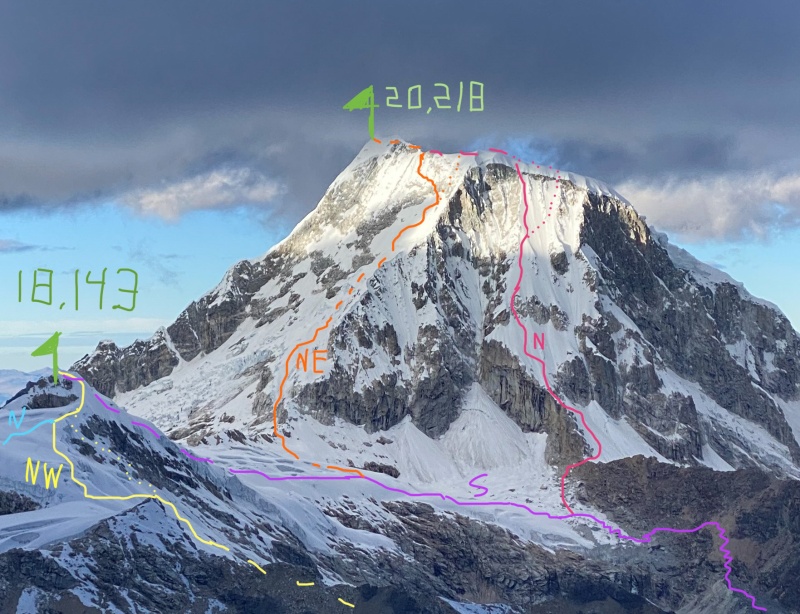

Nevado Ranrapalca 20,218 Nevado Tocllaraju 19,619 |

| Date Posted | 05/25/2023 |

| Modified | 05/26/2023 |

| Date Climbed | 06/20/2022 |

| Author | Camden7 |

| Cordillera Blanca Finale |

|---|

|

At this point the Peru trip reports are old, forgotten as they must one day be. The stories are tired and interests have moved on. But with the recent conflicts there my thoughts have been with the people I met in Huaraz. Each day I would nervously await headlines hoping that the tragedy hadn't crept north. Seems things are a little better now. With these thoughts on my mind I decided it was time to write the last piece of my trip reports. It was the trip of a lifetime and I must see through this written record so I may never forget it. I feel that I have useful beta on Ranrapalca and Tocllaraju. Everything else was written for me. And in part for Edgar and Tito and Julio and all of the others who made our visit so special. If you have not read Peru Part I, Peru Part II, Peru Part III, and Peru Part IV, I would recommend you do so (or at least skim through the photos), otherwise this might not make sense. If you pure goal is route info on Ranrapalca and Tocllaraju, you are in the right spot. For route info only you just need to read the bold sections. Chapter 10: Ranra Monday, June 19th After climbing Ishinca, we returned to camp and enjoyed the sunset, a display of molten ore in the great forge of the sky, a glowing beacon to guide the stars home. Then, as darkness settled on the glacier and our sleeping bags began to pull, a light appeared high above us. Then another. They were recognizable in an instant. "They're alive!" I called to the tent. The previous morning at about 3 AM (~40 hours prior), we had been high on Nevado Urus when we noticed lights on the north face of Ranrapalca, across the valley. As light blossomed into the unsettled sky, the headlamps clicked off, and soon fog obscured Ranra. We went about our day, finishing our ascent of Urus, then moving from 14,350 at Ishinca Base Camp to 16,300 at laguna Ishinca. We thought no more of the lights. The next morning we began our upwards trot. After an hour we reached a sickening sight. At the glaciers edge, just below the grand North Face of Ranra, was a tent. It had been collapsed to protect it from the wind. Nothing amiss here. Surely the owners were off on an ascent of Ishinca. But the evidence was overwhelming. The nights fresh snow was undisturbed and rested atop the flattened tent. Whoever belonged in the tent hadn't made it back the night before. We continued to high camp, climbed Ishinca, and returned to camp where we were joined by a German party. And as the day passed into night and no one returned to that lonely tent a thousand feet below, we began to get worried. So when headlamps flared to life on the towering Northeast face, it was a happy moment. Headlamps mean alive, no matter how bad the situation. But the relief was short lived. the more carefully we looked, the more apparent it became that they were hopelessly off route, way east of the rappel route. As we watched, they crept down the dark, hulking face agonizingly slow. Then their progress stopped. We knew they had reached the huge cliff blocking exit from their route. After a painful half hour the lights began to inch back upwards. then they went out. We talked with the germans about the possibility of a rescue party. It wouldn't work. None of us knew the terrain. it was dark and cold. Nothing good could come of us looking for them. We assumed they would make it down on their own, later, and worst case the germans were heading up in the morning, so they could look. We planned on taking our first rest day. Tuesday, June 20th The next morning came with cobalt skies and a valley-wide sense of optimism.

After a relaxing breakfast we roped up and set out to practice crevasse rescue and get a view of our route for the next morning. We saw a dog running on the glacier. Only in Huaraz...

The views were fantastic and Dad and I were both feeling great.

That was when we looked up and saw some climbers on the crumbling ice cliff splitting Ranra's northeast face. "What are the Germans doing?" we wondered. But with a careful eye the germans could be spotted higher on the face. There was only one conclusion to be drawn. Those headlamps from last night were yet to make it down. They had spent a full second night. Around noon, the two figures reached our camp, their throats too dry to speak, their minds too numb to think. We gave them water and tea. They were two young men from Japan, and their English was poor, but the story seems to go as follows; They had begun climbing the North face when they realized the climbing was much harder than they anticipated. the weather moved in and before they knew it the day was gone. the finally reached the ridge well after dark. Without emergency bivy sack or anything, they had spend an unplanned night at 19,700 feet. They spent the entire next day searching for the rappel route. In the late afternoon they finally found it, or so they thought. After they finished the rappels, instead of traversing to safety, they continued descending straight, delirious in their exhaustion and cold. When the found that their route cliffed out they began back upwards. That is when their headlamps died. And so the spent a second unplanned night on Ranra, this time at 18,300. When finally the sun rose, the began trying to climb directly up the ice cliff separating them from safety. the finally rejoined the standard route, and dropped down to hour camp. The north face route should take about 14-18 hours round trip. They spent over 60 hours on the mountain, all without a sleeping bag, bivy sack, or tent. They were badly frostbitten, scared, exhausted, and dehydrated, but by some miracle, they were alive. This story of close calls left us anxious for the coming climb, but our guide Edgar met us on the glacier that evening, and the mood once again improved.

We set the alarms for midnight and began preparing for bed. Just as sleep neared, the germans returned, loud, hungry, and disruptive. I got up to ask them about conditions and route. They were too tired to pass on anything helpful. It did take them 17 hours after all. After I returned to my bag, they continued to make noise, and when they finally quieted, a rare nervousness for the coming climb filled me. I lay there awake. That was when the alarm went off. Wednesday, June 21st, Shortest day of the year (in Peru) Not a heartbeat of sleep, and it was time to get moving. As we started walking all my apprehension fell away. This is where I belong. The dark glacier, the stars, the mountain. I was soon energetic and excited.

(See Peru Part IV for approach to high camp) From high camp the walk starts with a gradual traverse to the south-southeast, ascending 100 feet over about ten minutes to the Paso Ishinca at 17,500 feet. From here online descriptions tend to be vague, inconsistent, and rarely helpful. The route begins with a 0.15 mile ascending traverse due south along the east side of the ridge, well below the crest. This section gains about 300 feet of vertical. Interestingly, the snow here was shallow and brittle here, and a couple steps on rocks were required even in June. By August I would expect that crampons need to be removed. At the end of this section the nature of the route changes. The traverse places you in the bottom of an ice chute. Climb it! The climbing is easy, almost walking really, mostly around 45 degrees. When we climbed it a couple hard moved were required to breach a ten foot serac band, but it was otherwise technically easy. Angling left yeilded the easiest climbing this year, but that could change. The first 500 feet of climbing is subject to ice and rock fall, so be quick. Luckily avalanche danger is usually low due to the aspect. At 18,300 feet, above the ice chute, the angle relents to perhaps 30 degrees then eventually becoming flat. This is what I call the First Bowl, as it resembles a shallow basin above the ice chute. The route is straightforward and obvious here, until it reaches a stunning grotto at 18,400 (1/3 of the vertical done, woohoo). Here, the northeast ridge soars precipitously to the right, a mass of cracked granite that blocks the stars. On the left a jumble of seracs guards against further passage. It is worth noting that most of the route to here is free of crevasses (or was in June at least), but the First Bowl had at least ten small step-acrosses. They were not large or difficult to negotiate but a broken ankle here would be a lousy way to end the trip. From this beautiful grotto, the introduction is over.

This entire route is super cool, but this next section is one of my favorite bits of climbing I have ever done. The Ice-Fall. The route clambered left through seracs, crossing a maze of crevasses, spiraling around ice sculptures, then turning right and reaching the first technical section of the route. this section is supposedly highly variable from year to year. Most of our mountains were in rough shape this year, but this section was much easier than normal, so we elected not to belay or even simul it, but instead just climbed right through. The technical climbing is about 270 feet long, so if belayed out it is two pitches unless you choose to use a lot of rope. The climbing was probably around 50 to 55 degrees, but the consistency of the snow was great and the climbing felt really easy. Some people have reported this climbing to be over 60 degrees. Depends on the year I guess. Be warned, even in June there were two gaping crevasses that had to be crossed, luckily snow bridges remained. Late season or in a low snow year this could be seriously problematic. Be ready. The steep climbing ends as abruptly as it started, and the route crosses through some serac debris. Afterwords the angle levels out to nearly flat and a safe rest is afforded. Take advantage of it. Welcome to the Second Bowl, a small basin that rests below Ranra's upper ramparts. Take note of your surroundings as upon descent failure to turn left at the correct moment would lead to the same predicament as the Japanese. From here, the the route climbs 0.1 miles up through the basin. It begins as walking and gets imperceptibly steeper until suddenly you will want two tools. The bowl maxes out at 45-50 degrees before dead-ending into a huge bergshrund that slashes all the way across the face. Pull out you belay device. 1,200 feet stand between you and the summit. I don't exactly remember but I believe it took us only 3ish hours to here. Another almost 5 would separate us from the summit. It was cold and dark, but I remember one thing very clearly. When you are at the top of Bowl Two, you are already on steep terrain. When you look up, there is nothing but blackness. No stars. Then if you look up further, so far it hurts your neck, finally, a few stars twinkle at the horizon. There is little in the climbing world as intimidating as being on something steep and the terrain ahead being so much steeper that it blocks out the sky. The first 'shrund was plugged with snow somewhat, but still huge and scary. Once across one of the abundant but sketchy bridges, a 8-10 foot ice step bars further passage. It is close to vertical and feels exposed right above the bergshrund and the mounting exposure below. Once above it, the leading climber will be out of view, not that it matters in the dark. What follows is the Wall of Despair. All pitch lengths assume the use of a 70 m rope. After the 'shrund, the leader should continue the full 70m up the 55-60 degree snow slope. After this pitch, another 70m pitch of gradually steepening snow follows. There is another smaller bergshrund on this pitch that must be handled. It is easier to deal with than the first one, but still a challenge. The Wall of Despair is cold and endless and dark. Don't lose hope.

Above: Taken on descent, this gives perspective of how steep there terrain is even before reaching the rock and the steeper upper pitches. At this point the rock band looms over you like a legacy you can't quite fill. For the last 200 feet it has looked close enough to touch. It remains a specter on the horizon. Our guide (more of a payed climbing partner with route beta) messed this one up a bit. Edgar is a fantastic guide, very safe, fast, and competent. He had never successfully summitted Ranra. The thing is a hard mountain. We ran a single pitch all the way from here through the rock band. DO NOT DO THIS! As Edgar lead, despite his careful movement he knocked numerous large rocks. We found this problem a bit too late, so I move the anchor 30 feet to the right while Dad belayed Edgar on the crux of the entire route. Despite my hasty relocation of the anchor and belay-station, it was too slow. Crunch!

Instead of running a single long pitch up through the rock band, climb a 100 foot half-pitch up the 60 degree snow to the edge of the rock, at least 10-15 feet right of the bottom of the gully. The Wall of Despair is now below you. After the crux pitch, it all gets better from here. It was about right here that the world became light.

From the belay at the bottom of the rock band, climb the narrow gully. I am not a mixed climber so it is probably easier than I thought. I like snow/ice, I like rock, not so much together. The climbing moves were 5.4 at the very least but the dry-tooling and sections of brittle ice were scary AF and the gear was nonexistent. Edgar slung a small icicle and placed one very untrustworthy screw on the entire 120 foot pitch. There was a fixed anchor at the top, which we reinforced with a couple nuts. The rock is rotten and the ice brittle. Even if it is only M3 or M4 it felt really hard and scary. Later in the season more rock will be exposed and this tough pitch will be longer. Come to think of it, late June/early July is the right season to do this route.

Above: My dad topping out the rock pitch Two more pitches lead to the ridge, about 200 feet each of calf-burning 65+ degree snow (and the occasional 4th class rock problem) with heart-stopping exposure and quite literally breath-taking views. These are my two favorite pitches of climbing that I have done anywhere. SO COOL!

When you reach the ridge at 19,900 feet it is something out of a dream. You can take off your pack. Regroup without an anchor. Eat some food. Look at the sweeping view from Chinchey to Huascaran to the Cordillera Negra. Gape at the remaining route to the summit. What, you didn't think you were done, did you?

First order of business: break a trail over to the summit mushroom. The Germans had broken one but it had mostly blown back in. Thankfully the snow was only thigh deep for us but plenty of reports call it chest deep. Sadly, many groups turn around here, unable to push through the heavy snow at such a great altitude. After crossing the plateau, we climbed a direct line across the bergshrund to the saddle between the three "summits". The middle is the highest, but doesn't appear so in the previous picture. It was about 60 degrees, horribly unconsolidated, and the snow bridge was very iffy, to the point that it broke as I stepped off it, but we still didn't belay. Perhaps should have but we were sick of it after coming up 6 pitches.

If you shoulder further along the plateau an easier 45 degree pitch can be ascended instead (we came down this way), although the bergshrund was still challenging to cross.

Above: Dad and I at the top of this final climbing pitch. The great plateau lies below and the spectacular expanse of the Andes spreads in every direction.

From the top of that last section only 40 feet remain. Nevado Ranrapalca, Snowy Mountain of Branching Rock (in Quechua), does not yield. There is still climbing to be done.

When you get past the 'shrund and reach that final 20 feet of ridge, things get wild. On your right is a large cornice, steer clear. On your left is ... well, not a whole lot. A fall here would put you in Laguna Perolcocha, 5,000 feet below, unless a crevasse ate you first.

The descent off of Ranra is long, arduous, and time consuming. Begin by retracing your steps back off the summit mushroom and across the plateau. The initial downclimb is scary. Have your strongest climber go last. We descended the lower angle pitch to the left as I mentioned earlier. If that is blocked by the 'shrund, you may have to descend the more direct route (that we went up) and a rappel may be necessary. Don't plan on an existing anchor or ice for a V-thread/0-thread. Have a picket you are willing to leave.

Once back at the top of the northeast face, things get challenging. There is a tattered rock anchor available for the first rap, but I would back it up with nuts you are willing to leave, or leave a picket. The first rappel is about 200 feet or so. Two 70m ropes are a must. The next anchor is also in rock, this time more solid. We backed it up anyway. Another 200ish foot rappel brings you to the top of the rock band. A third and final rock anchor is available. Back it up. Rappel a full 70m down through the rock band, traversing right once back on snow if you can to get clear of rockfall.

From here you could theoretically downclimb the remainder of the route, but the next 470 feet exceed 60 degrees the entire way and any fall here would be fatal for the whole rope team. Due to these hazards we elected to complete two more very stretched rappels off of pickets. It was sad to leave pickets on the mountain for both economic and ethical reasons, but as the mountain is rarely ascended and no existing anchors are in place, it is the only safe way down. When the final bergrund is cleared, the nature of the terrain relaxes as the Second Bowl is reentered. Cautiously downclimb to the flat area at its base and enjoy a well earned break. The views are spectacular.

Retrace your route back to high camp. The icefall may require 1-2 rappels some years, but for us it was easily downclimbed. Overall the route took us 13.5 hours RT, while it took the Germans around 18. I would say the route could reasonably done in 10-15 hours by a fast party, especially of two climbers instead of three, but for parties that are not well acclimated or don't have their ropework dialed, 16-22 hours is more realistic. In terms of gear:

After returning to camp we napped briefly (about 30 minutes) then began packing up. The walk out is only a few miles long and 3,000 feet down. The lower portion of the glacier is crevassed but we neglected to use ropes, deciding that the danger was limited along the trail. We finally arrived in base camp at 8 PM, an hour and a half past sunset, after 19.5 hours of hiking/climbing, and for me more than 36 hours without sleep. Brutal. We set up camp messily in the dark and piled into our bags after a hurried dinner. This was my second best night of sleep EVER, beat only by the night after our summit attempt on Huascaran. Chapter 16: A Final Chance Thursday, June 22nd The sun illuminated the eastern sky, slowly creeping onto the ridges above then tumbling down to camp. Edgar packed up and began the trip back to Huaraz. Hours later we finally stirred and climbed from our bags, well after eight. The plan was to spend the day relaxing. Do absolutely nothing all day. But the Garmin InReach had other ideas. The weather forecast read something like this; Thursday: Nice in the morning, heavy clouds in afternoon, Friday: stormy and snowing, high wind, bad - but Saturday: Hurricane force wind, deep snow accumulations, wicked storm. It would shut down the peaks for the last few days of our trip. We had a flight to catch out of Lima on Monday night. If we wanted Toclla, we would have to get creative. Oh, and one other thing; the standard route is closed. Guides will take you up it then stop at 19,200 below the summit mushroom, telling their clients they had reached the end of the road. A few days prior, a group of 20 Ecuadorian guides-in-training had set out to aid up the mushroom, armed with pickets, ice screws, charming optimism, and enough confidence to make the glacier rearrange itself to their will. They backed off. At some point gaping bergshrunds with overhanging floofwalls on the other side become a challenging problem. With the weather closing in and our return deadline coming quick, there was only one thing to do; pack up camp and carry it up to Tocllaraju high camp that day and hope for an improbable weather-window the next day. But if you have never tried to convince two people who climbed Ranrapalca yesterday to pack up camp and move, I will tell you that little in life is more difficult. Tired people are stubborn. We refused to move camp. We refused to abandon our chance at another climb. Deadlock. In the end, a compromise was called for. We would carry all of our gear (ropes, harnesses, crampons, helmets, food, pickets, etc.) up to a cache at the edge of the glacier. Then we would return to camp. The next day we would climb Toclla in a single push from base camp, moving fast on the lower slopes since we would have packs full of feathers and clouds. Hindsight 20/20 this was a total waste of energy, but whatever. The route from base camp at 14,350 to Tocllaraju high camp at 16,725 is not super hard, but it takes some effort. Note: Unlike the paths into base camp, and from base camp to Ishinca Moraine Camp, this route is too rough for mules. If you want it up there, you gotta carry it. The route leaves the great meadow of base camp at its northeastern-most point. There is a small braided stream that you may need to cross, but it is easy. Follow the left bank of the stream upwards. The trail here is very faint and braided for the first 0.15 miles past the refugio. Suddenly all of the trails converge and get very close to the creek, traversing along the steep bank where the creek meets the edge of the slope coming down off of the ridge above. The paths then begin switchbacking up through the boulder-strewn ancient moraine, following the small ravine between the ridge on the left and a large moraine on the right. The trail will abruptly stop this "gentle" climb at 15,050 feet, 3/4 mile past camp. Now, the trail begins its steep climb up towards the Paso Urus and the west ridge of Toclla. The trail now ascends due north up very steep, very tight, and somewhat slippery switchbacks to 15,600, until getting less steep, but rockier, and angling more north-northeast. At 16,000 feet the angle relents but the walking has morphed from sandy soil to full on boulder-hopping. Cross the lower angle boulders, passing a series of memorials and crosses that remind you of Toclla's danger that seems so easily hidden within it's beauty.

By 16,200, the trail end almost completely, and an ascending traverse northeast across large boulders and slabs must be completed. It begins with large but stable blocks, soon yielding to a series of slabs and ledges, none exceeding class 2+, but the route was not obvious and verglas plus fresh snow complicated matters. In June, the rocks eventually forced us onto shallow and annoying snow at 16,600, but as we approached high camp dry ground returned. I would guess that this approach should take 2-3 hours from base camp with day packs or 3-5 hours with overnight packs. High camp is a small sandy hollow with flowing water, some protection from the wind, and room for no more than four or five tents. The platforms are a hot commodity. If there is no space you could continue another hour or so to glacier camp at 17,300, but this would require extra fuel to melt snow for water.

We dropped our stuff, the climbed up to the ridge to scout the route for the morning. From High Camp, the broad ridge can be gained with 180 feet of 35 degree snow, or some fun and high quality 3rd class rock on the left side of the snowfield. We hit the pillows pretty early and watched the sunset out the front of out tent.

Friday, June 23rd Wake up at 1. Felt awful. Start walking. Felt worse. Try to eat. Nearly die. We were at about 15,000 when I said, "I am so wrecked and exhausted. We are not getting anywhere near summit today. We need to make it back to high camp to get our gear, but then we should turn around." So that set the tone for the morning. We finally reached high camp an hour behind schedule, having reached it faster the previous day, while carrying all our gear. So much for making this part easy. After collecting our gear, we decided to push up to the ridge, just see how far we got. As we began walking away from the pass, it became evident the slog-like nature of the first part of the route. The first 3/4 mile gain 500 feet on a long false-flat that follows the gradual ridge. Finally a couple crevasses start to but in to make it a bit more interesting, and at 17,400 the route finally begins to steepen a bit.

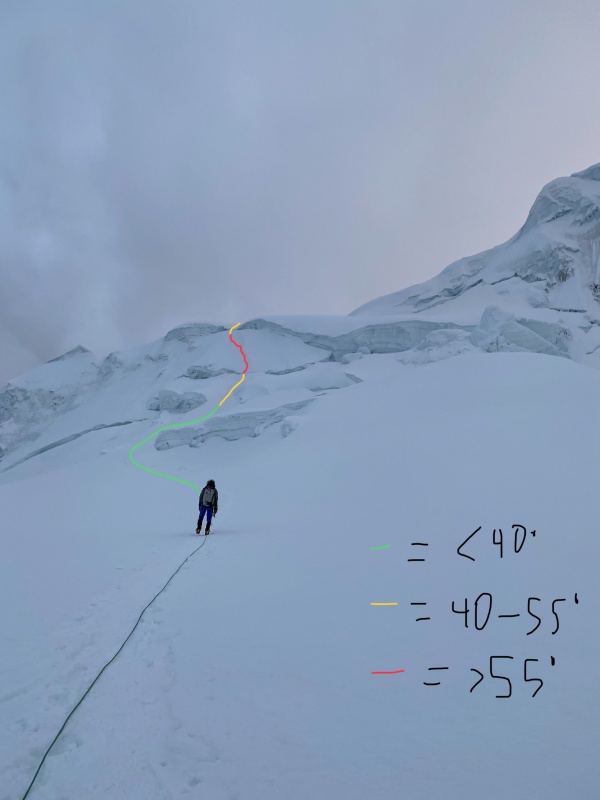

Above Glacier Camp the route becomes "The S Section" Here the slope steepens to a series of 35 degree rollovers separated by flat areas. The whole thing is riddled with long crevasses. Even in June we had to make numerous long end runs and 2+ foot step-acrosses, and I have heard that by August they can be impassable. At 18,100 the terrain mellows but the headwall looms. Miraculously, as exhausted as I was, I found energy to push on.

Traverse briefly left under small seracs. Some parties may choose to start belaying here. We simuled the whole headwall. Start with a section of gradually steepening terrain, I would say 40-50 degrees (perhaps 150 feet?). This will deposit you at the bergshrund.

There was one challenging move across the 'shrund, then steeper climbing immediately followed. Although it realistically only exceeded 55 degrees for a short time, the snow was unconsolidated and slippery, and the pitch does traverse, so I found it a bit spooky to follow on simul, as it was really cold and my hands did not enjoy removing the pickets. The angle relents as you cross through the final serac gate and enter easier terrain above (circa 18,600). Once on the Northwest ridge, the technical climbing is over for anyone who intends to stop at 19,200. As we gained the ridge the forecasted wind and snow ramped up. It became total white out conditions and so humid that rime was accumulating on our harnesses and gear while we climbed. Within 5 minutes we had 3-inch long snow feathers growing off of our leeward sides. The climbing on the ridge is scenic and easy. I bet the views are amazing, but even in fog it was fun to observe the stunning ice sculptures. The 600 feet of climbing along the ridge are probably fluctuating between 30 and 40 degrees. Then suddenly, at 19,200, the casual stroll comes to a sad conclusion. the mushroom rears. The fog and wind scream "TURN AROUND" and the mountain itself almost seems to forbid life from reaching any higher. But then the fog clears and we can see for a second. We begin navagating up the steeper muchroom, just directly up it. It seems too easy. Too good to be true. And so it is. A 20 foot wide crevasse says NOPE!

We try to go right. I throw dad on belay while he leads a gnarly traverse across 70 degree terrain out to a ledge. I follow him out. The east face direct finish looks so close, almost within reach. A huge crevasse blocks access. After a bit more exploring we returns across the traverse. We can't go straight up, we can't go right. That leaves left. We follow a faint set of tracks, a few days old. It leads to a small knoll with a discouraging view of the summit cliffs. The tracks end. Right here, at 19,300, the route ends. And that's that. It has been that way for a few years.

We came from the right, up doesn't work, but what about left?

Outta luck. Unless... what if... do you think... ... ... "Put me on belay, Dad!"

I kept going, crossing bridge after bridge under teetering seracs for 200 yards. At some point the rope pulled tight. Dad pulled out the anchor and began following me. I pushed and pushed through the labyrinth, and to my astonishment, it suddenly ended with a couple steep icy moves onto a spine. There, at 19,450, I had found the North Ridge. I didn't have a camera on me, so no picture documents what I saw from there, and I may be the first to do so in a while. We hollered back and forth. It was late in the day. The storm was getting worse. We were the only people up there. The mountain had tolerated our intrusion, but it was done playing games. It was time to go down. So we did. I could see the summit. A 20 foot tall 70 degree ice step guarded the upper ridge. Then all that remained was 150 feet of 50 degree ridgeline. It was perfect. It was beautiful. The exposure was absurd. The position was legendary. But it wasn't the right decision to go up. So we descended, content to know that the egg had been cracked, and that we had perhaps found a route bypassing the summit mushroom. Had I opened it? We began back across, and soon dad reached the relative safety of the other side of the crevassed icefall. He stopped to adjust something in his pack and have a sip of water. Thats when a bridge collapsed. I was so careful to step just where the footprints were. But I guess it was one set of footsteps to many for the crumbling bridge. I had been standing one moment, and the next I was arrested, hanging from my tools with my feet dangling in empty space. I remember staring past my crampons into the void, the gaping, yawning, stomach of the glacier. I remember noticing the rope ahead of me was slack. "Keep on walking!" I called. He did, and soon the rope was once again tight. I did a pull-up on my tools and scrambled over the edge. For some reason I remember this whole thing in a comical light, and we make many jokes around "Keep on walking!" So maybe it wasn't a good idea to cross that mess. But the route goes and i am proud to have made it higher on the northwest ridge than anyone has for a while. It was a neat experience. And now maybe some of you can get to the summit for me, finish the last leg of my journey.

We return to camp uneventfully, and watch smugly from our tent as the storm hits hard. We don't want to hike out in the weather and our burros are arranged to meet us on Sunday, so we know we can sleep in and take the next day totally off. If the weather was better rock shoes would be fun for bouldering around camp. there is lots to be done. Saturday, June 24 35 mph wind, sideways freezing rain that accumulated ice on everything. All day. Sun up to sundown. The mountains were buried in fog and snow. We cozied into our bags and dug in for the duration. I daydreamed of a plate of Lomo Saltado. Lots of climbers risked the elements to walk over to "The Americans" tent and talk to us about route and conditions on Urus, Ishinca, Toclla, and Ranra. Of course conditions were changing fast, but we had just done them all (sort of). After backing off Huascaran it was a really nice feeling to end the trip with such redemption on such wonderful peaks. The Quebrada Ishinca is off-putting to some people because it is commercialized, but it is a place of magic and dreams coming true so don't overlook it because of it's popularity. The Blanca might not be a secret, but it isn't crowded at all, especially compared to Colorado's mountains. A few other parties in the whole range seems to be pretty standard. I guess people are afraid of how hard the mountains there are. I am, too, now that I know how brutal the conditions, sand-bagged routes, crevasses, and weather are, and how powerful and steep of a range it is. I will be back (maybe 2030?) if the current unrest settles down by then. Very interested in Chopicalqui, and Palcaraju, in addition to some obscure stuff. I hope it can happen for me someday! Chapter 12: Return - Roadblocks and Runways Sunday, June 25 We packed up early and after loading our mules (only 15 minutes late to arrive), we set out down the trail.

The hike out is about seven miles and it goes quick. When the trail gave way to road it was an emotional moment. I was so ready to go home, too tired to continue this. But it was my first international mountaineering trip, something I had planned so much, spent so many hours fantasizing about. It still felt like we were about to set out, as if we had just watched a month-long movie about people cooler than I could ever be. Even now I lie awake some night wondering if it was really real, if I could ever do it again. The adventure was over. Right? After collecting our gear from the burros they disappear up the road. We waited for one of the abundant taxis for quite a while when we realized that there was no traffic on the road at all. No private cars, no taxis. We turned on Verizon for the first time on the trip and tried to call the taxi driver that had helped us a couple times previously. No cell. I spent a few moments mushing together my weak Spanish in my head before asking a local Quechua lady if she knew how to get a taxi or cell. I still remember her smile and response. We must have been quite the sight. "Abajo." Her Spanish seemed little better than mine, and the only word she offered was this. Again and again. "Abajo. Abajo." So with a 50 lb pack on each of our backs, a 20 lb day pack in our outside hands and a 70 lb gear duffel carried between us, with the burdens of the last month pressing us into the ground, with our shoulders slouched, our stomachs empty, and our muscles complaining with every breath, we started walking side-by-side down the road. After an endless 3/4 mile walk the small houses of the tiny pueblo Huillac. Here everything began to make sense. The road into the trailhead had been ripped up for an irrigation project. After a very difficult to understand conversation with a local farmer he offered to drive us back to Huaraz, except we would need to take a long detour over a long pass. Surprisingly his price was fair. He moved a bunch of work tools from his Toyota Carola. The hatch didn't open so we stuffed our gear in from the side doors. He hopped in. It wouldn't start. Eventually we were able to pop the clutch and get it rolling. he began zipping up the narrow switchbacking road through the beautiful subsistence farms. Our driver drifted the car around a few of the downhill switchbacks, and after another hour we returned to Huaraz. We immediately dropped our stuff off at the hotel, then we ordered three entrees at the restaurant across from Olaza's. After 4 scoops of ice cream (each) we started unpacking our stuff, went out for a second dinner, then repacked everything for air travel. We went to bed for the last time in a beautiful country that had treated us so kindly. The next day we would make our final preparations then catch our 11:15 bus back to Lima for our 12:30 flight. Monday, June 26 Once all of our stuff was ready to go we walked around in search of a breakfast place and found this:

This little restaurant in downtown Huaraz has great coffee, refrescos, empanadas, and baked goods. I wish we would have found it earlier in our trip. I will be back here next time I am in Huaraz. After returning to our hotel Tito Olaza (hotel owner) offered to drive us to the bus stop. We walked towards the building to check in. A young American woman paused us. "You're not going to Lima," she said. "Yes, actually we are," I responded stupidly. "No. You're not. There's no bus today." Um. What?!? "But we have a flight!" We hustled inside to get details. All busses were cancelled for the next week due to roadblocks, riots, and protests over gas and fertilizer prices and political disagreements with Pedro Castillo's inability to get pro-agricultural legislature past the elitist and corrupt congress (and the rest is history...). Well that sucks. A week, huh? That isn't gonna work. We approach a man from florida and suggest we split a private driver to Lima. He says "Absolutely not. That is like crossing a picket line. It is so dangerous. I am gonna just wait the week." But we are too tired to do any more climbs, we desperately miss Mom, miss homemade food and our own beds. We are going home and we are doing it today. Tito takes us back to the hotel. He is such an awesome guy. If anyone who reads this ever goes to Huaraz, stay at Olaza's, support Tito. After returning to the hotel, Tito calls his brother, Mauro. He is the third and final of the six Olaza brothers we got to meet. He says he can drive us to Lima. It might be dangerous. It will take a long time. We might miss our flight. There is a good chance the car will have stones thrown at it, the windows broken. But he thinks he can get us there. So we go. The drive up to Conococha Pass is uneventful. The steep switchbacks down through the Negra are beautiful and go smoothly. The long descent from 13,500 feet to sea level goes mostly smoothly. It is amazing the dry, rocky desert dotted with agriculture - sugar cane, maize, bananas, and aji panka chilies.

We stopped to look at the spectacle. A friendly farmhand handed us 6 or 8 to take with us, free of charge. So much kindness down there. Then we reached the Panamerican highway things changed a bit. Armed police with riot shield lined the streets in Patavilca. The blockade there had just been broken. The heavy police presence continued through Barranca and Supe. Things seemed to calm down a bit. That is when we reached the town of Medio Mundo. Middle Earth. From here the story gets weird. "In any... story, but especially a true one, it's difficult to separate what happened from what seemed to happen" –The Things They Carried by Tim O'Brien The many lane highway was completely stopped at Medio Mundo. Gridlock style. Buses and huge semi-trucks were piled up in each lane, dead stopped. on the left side of the road some passenger vehicles were squeezing between the trucks and the guardrail. We followed them, but after a short distance the driver of a collective was shouting to everyone something about turning around. It doesn't go. But Mauro follows a different set of rules. He forges onwards in the ever narrower lane until he cannot possibly go further. I semi is pulled against the guardrail, leaving only four feet of space. I swear Mauro just turns off physics and drives through it. I will never understand. After another few hour-like minutes we suddenly reached the front of the line. It was terrifying. At least 15 impressively muscular farmers were blocking the road with tires, concrete, cones, rocks, and themselves. And now a single fancy little SUV just became the center of attention. And who is in the back but two defenseless Gringos. The situation was rather uncomfortable. One of the rioters placed a large fragment of concrete in front of our front right tire. He makes pointed eye-contact and says silently but perfectly clearly, "Hold it there. This road is closed." But of course Mauro has 4-wheel-drive, so he just drives right over the concrete. It was about then that John's haunting words flooded to our lips and threatened to become our own. "It wasn't funny." and all the rest. Terror. We are now suspended in the midst of the debris blocking the highway, surrounded by rightfully angry men with rocks and we are now a few car lengths ahead of where the semis and buses were stopped. Things are dire. But then something weird happened. it was a whole conversation in a glance between Mauro and a rioter who seemed to have authority. Mauro's eyes seemed to say "C'mon, we're all just trying to make a living. These Gringos paying me big. You let me do my thing, I let you do yours?" And so in wild swing of temperament, the lead protester rolled aside a massive tire, flashed a bright smile, and waved us our way. Not 3 seconds down the road Mauro exhaled and said "Whew! That was exciting!" Indeed. We actually made great time to Lima because the protests had the interstates free of cars. After having a nice Lomo Saltdo dinner together, Mauro dropped as at the airport. We gave him every last dollar we had, three more the we had promised him, paying in mostly in fives and ones, having neared the end of a long trip of ATMs and conversions. And with the Peruvian roads behind us, we dragged our hundred of pounds of stuff through the double doors, and into the glimmering airport. We were more than 4 hours early to our flight. Things seemed to be looking up. But Aeromexico Lima had other ideas. We had payed for three checked bags online ($60 a piece), which had all been charged on my dad's credit card, and Aeromexico said we only had one. I sat patiently on the floor while Dad went through spanglish yelling matches with three different AeroMexico employees, and after more than two hours they so kindly let us purchase our extra checked baggage, that we had already paid for, for the low low airport price of $125 a bag. then when one of them didn't meet the weight requirement by like two pounds, they made us repack a bunch of stuff into our carry-ons, which would still be on the plane adding the same amount of weight... fucking airport bureaucrats. After surviving that mess, security was reasonable, and we boarded our plane before too long. We departed just before 1 am, and landed by 7. On the way down we had been lucky to snag a couple last second, super-sale business class seats, so our baggage was already connected from Denver straight to Lima. On the way back we were not so lucky, so we had to recheck our bags. After clearing customs (even though we weren't even leaving the airport, so that took 45 minutes and we had to carry all our stuff), we went to the rechecking spot, and they were like no your bags are more than 40 lbs we can't do this here. So then we were told to carry all of our 250+ lbs of gear outside the airport, around to the main entrance, check our bags there, go back through security, then go to our gate. Why is air travel like this? So we finally lug all our stuff to the right spot, where we were helped by the single kind hearted person in the air industry. We were pretty flustered at this point, and just exhausted, so she helped us get everything settled. the weight requirements on the bags had dropped 10 lbs or no reason for the next flight, but she turned a blind eye and we were soon on our way back through security to our gate. Two days later we climbed Paiute and Audubon with Mom and we went on to have many great adventures around Colorado, my Dad and I finishing the Centennials on September 16. It was truly sometime in late August, well after school had started, that I woke up and realized I was finally no longer tired from Peru. The month-long trip was a memory that I will always hold close to me. I learned so much about mountaineering, but also so much about Peruvian culture, about team dynamics on expeditions, and mostly about myself. I feel so blessed to have had this opportunity and to have come home safely. If anyone has any question about anything Cordillera Blanca-related, I would be happy to help. Today was the last day of my sophomore year in high school. Now within a week of the trips anniversary, my sights are set mostly on this summer's goals, but a day never goes by without me thinking about the people I met, the memories I made, the air that I breathed. Be safe out there, everyone, and good luck on all your adventures! |

| Comments or Questions | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Caution: The information contained in this report may not be accurate and should not be the only resource used in preparation for your climb. Failure to have the necessary experience, physical conditioning, supplies or equipment can result in injury or death. 14ers.com and the author(s) of this report provide no warranties, either express or implied, that the information provided is accurate or reliable. By using the information provided, you agree to indemnify and hold harmless 14ers.com and the report author(s) with respect to any claims and demands against them, including any attorney fees and expenses. Please read the 14ers.com Safety and Disclaimer pages for more information.

Please respect private property: 14ers.com supports the rights of private landowners to determine how and by whom their land will be used. In Colorado, it is your responsibility to determine if land is private and to obtain the appropriate permission before entering the property.