| Report Type | Full |

| Peak(s) |

Tower One |

| Date Posted | 05/22/2021 |

| Date Climbed | 08/08/2020 |

| Author | dannyg23 |

| Additional Members | BillWright |

| Red Lining the Yellow Spur |

|---|

|

The following is about climbing a route in Eldorado Canyon fast.

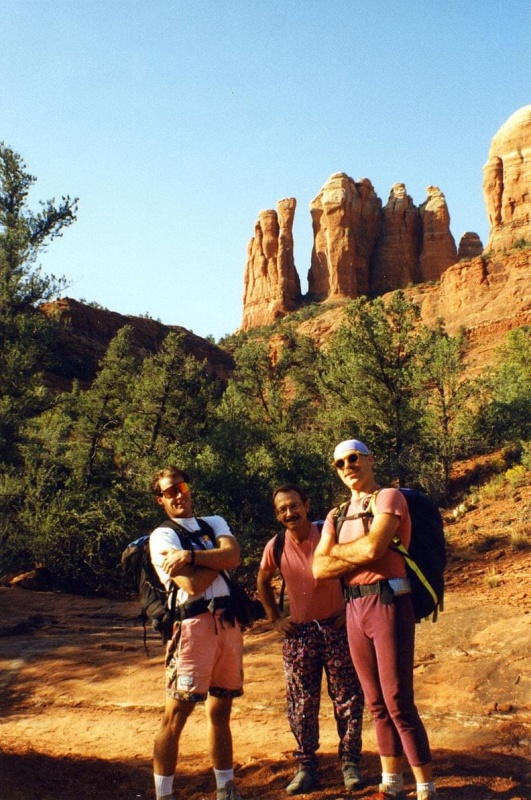

I didn’t sleep well the night before. I had the route and gear so memorized that I saw myself climbing it whenever I wasn’t distracted. The insides of my eyelids like screens showing the same thing on a constant loop. In partial acceptance for the futility of sleep, I transitioned to sitting on the living room couch. When that got to be too much I opted to drive over and wait in the parking lot instead. As I pulled in I saw that Bill was already there waiting for me, way before we planned on meeting, and I guessed that it was the same with him. I sat down on my tailgate and pulled my hood against the biting wind that flows along the Bastille corridor every morning. It was still dark, so we had plenty of time. To fill it, I started loading micro-traxions on our rope. Then I tied an eight on a bite to a locking biner, and clipped them all together in a chain. A strange arrangement to be sure. Bill sorted out our rack, which in those days was 5 cams, and 15 draws. Neither task took much time so we just had to sit on my tailgate, wait for the sun and try to settle our minds. I probably said something like “we’ll get it today for sure”. Bill probably agreed. These are the kinds of conversations you have when you’ve long become incapable of distracting yourself with other topics. Bill had taken me up Yellow Spur the summer prior, leading each of the 6 pitches in his usual efficient way so we could get things wrapped up in time for work. This was in the days before running shorts and trimmed down racks. These types of pre-work adventures are the foundation of our friendship, each of us wholly committed to finding out what sort of audacity can be converted into a morning routine. I loved the route.

Later, friend and local legend Stefan Griebel posted a picture of his Naked Edge rack laid out in order on his tailgate. Stefan—with the late Jason Wells—was at that time holder of the Naked Edge speed record and the rack they used for the entire route as a single pitch wouldn’t have gotten me to the base of the climb.

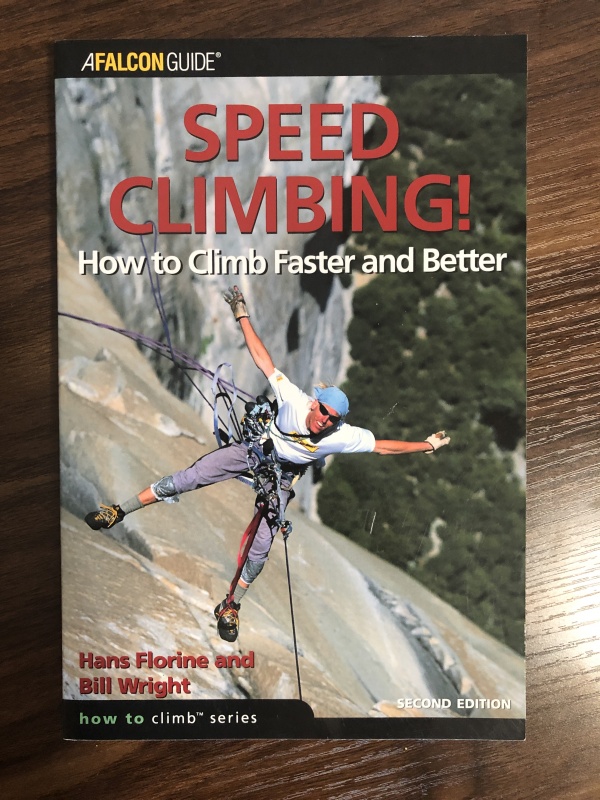

Bill was excited and eager to mimic this on our poor man’s Naked Edge. In hindsight, I had no clue what I was signing up for here. All I brought was an ATC, and when Bill saw this he just told me I would have to avoid climbing faster than he did (not a problem). This information was essentially the only instruction I got, apart from ‘don’t fall’. This is how I remember it anyway, but in reality Bill is never short with words. I’m sure he had plenty for me that morning, but this interaction serves as a great example of how things work between us. Bill has tremendous and unwarranted faith in me, and I do my best to live up to it. Bill brought two microtraxions, which are a little device I had never heard of but was told would keep a fall on my part from ripping Bill to his last piece, and likely death (He was up front, usually very run out). Alright then. The popularity of this strange vertical dance routine we’ve allowed into the Olympics notwithstanding, the most well-known speed climber might be ‘Hollywood’ Hans Fluorine. Between blistering fast lycra clad burns up the Nose, Hans even co-authored a book called ‘Speed Climbing’. His co-author? Well, that’s my friend Bill. So although I had no clue what was going on; Bill did.

Near the top, Bill had opted for the 5.10b finish which I had never done before and as the wind started to rotate my body off the tenuous position at the arête I felt the fear of God. I wasn’t up for finding out what would really happen if I fell on the microtraxion and the desperation I felt was pure. I hung on, but as evidence of my heightened state it would be another four trips up that thing before I managed to lead it clean. What a fucking rush. We climbed the six pitch route in about 52 minutes and went bridge to bridge in 1 hour 31 minutes. The fact I recorded these times is telling. After that initial simul-climb up the Spur, I found the idea that we could go faster pretty hard to avoid thinking about. We had walked to the base of the climb, and back down from the top after all. Plus, that was just my second time on the route and I was all but paralyzed by fear the whole time. In hindsight, I doubt we have ever been so reckless as we were that morning. The chances of a fall on my part were about as high as they would ever be, and we protected the entire 600+ foot climb with two microtraxions on a 130 foot rope. In other words, Bill was protected from my mistakes for less than half of the climb assuming perfect spacing (which we didn't have). I didn’t think about that though, foolishly. I made no mistakes so I didn’t have to. I just thought about how much faster we could go. I had also discovered a goal to shoot for, finding (in Hans & Bill’s book no less) some documentation showing that Josh Wharton and Kevin Cochran had gone bridge to bridge in 58m10s.

That following summer, we set ourselves to the task of shaving time. From the beginning we went relatively fast by forgoing any belays but in reality we were moving at the usual snail pace that makes our sport so boring to watch. The first thing, at least on my part, was to work the individual sections of the route that I slowed down on. On top rope I ran laps on the P3 flares, which are just 5.8 but felt insecure.

I also (this sounds dumb, but it’s true) needed to learn the approach and descent, and screwed both of them up more than one time. Next, we needed to determine our strategy for gear, which of us would lead, who carried what on the approach and descent, and how to most quickly transition between running and climbing. Perhaps more important than those things, was to get a feel for where the other guy was at all times. We needed to know if the other guy was climbing something easy or hard, if he was going to slow down soon or speed up. We purchased a 100’ rope, and found that it was significantly faster to have Bill lead the climb. Learning how to climb and belay at the same time was difficult for me, and I was quite afraid to allow any slack into the system at first (Bill was often very run out above) which was a great hindrance on speed. I also had to learn where on route I could deal with the ever growing mess of cams, slings and micros I collected on my way up. Looking back at my tick’s on Mountain Project I can see that we had started the process in June, and began gunning for it by early July. I thought I was on top of things, but now I’m not so sure, given this data. It is difficult to look back on where you were from the perspective of where you are now. I have such a better understanding of the strategies we were using now. In my mind, I had stopped allowing for the possibility that I could fall.

This is the great paradox of risk assessment. If you logically consider the risk you are taking, you would never take it because the reward component is too hard to square. I’ve solo’d many miles of low risk flatiron rock here in Boulder and I can tell you that I just don’t think I’m going to fall, ever. Of course I know that it is possible to fall. I even know it is possible for me to fall, but I simultaneously hold in my head the idea that I definitely won’t. If I couldn’t perform this Orwellian doublethink, I would never be able to go up there in the first place. I once witnessed a friend, much more capable than me, fall 40’ off the back of the 3rd Flatiron surviving by the grace of whatever God he favors. This is a guy whose skill and competence in that terrain is unimpeachable. I was scrambling around up there just a few days later, certain both that I could fall and that I wouldn’t. Both are true. With complete and total focus on the task, nobody is going to fall on a climb they know well and that is within their limits. Exterior hazards excluded, the main problem is that sometimes that focus gets compromised. Of course, this is not a unique or radical mindset. Everyone who has ever driven a car has it also. The primary difference is that a solo rock climber relies entirely on their own skill and competence, and the person in a car gets at least some assurance from the skill and competence of people that make air bags. Most people do not like to be in situations where they are in charge of their own safety. I was too inexperienced for an honest assessment of the risks up on Yellow Spur to mean anything consequential, however Bill was not. Before it was over, we had increased our quantity of micros from two to four. The portions of the climb in which Bill could pay for my mistakes were reduced to under 1/3 of the route: the final 1½ pitches, and most of pitch four during which I was on easy ground. Bill’s mantra, which he borrowed from Hans, is that he climbs faster when he feels safer. That’s true for me too. If pressed to solo Yellow Spur, I don’t believe I could rip up that thing at anywhere approaching the speed we ended up at, if at all.

Was what we were doing safe? Well… no. The safety of each climb, and each climber exists on a spectrum. No climb is wholly safe. I took exceptional risks when I slithered up my first route, placing brand new cams and tying in with a knot I learned on YouTube in the parking lot. I take almost no risk when fear has me sewing up climbs at my physical limit, cam spacing measured in inches and a fall all but guaranteed. Throughout all the insanity that followed we never had to find out what falling meant with this system, but we had considered that possibility. I am at least confident in my approach to the project, which despite all of the madness associated with climbing at breakneck speed, allowed for humility and error. I began to think about it like a dice roll, and since we planned to roll the dice many times I wanted to make sure I liked the odds. We started out by chasing a time that Josh and Keven likely don’t even remember setting, but on July 11th, my good buddy Jon Oulton blazed the route with his partner Nodin de Saillan in 57m02s. They bested Wharton’s time, and snagged the FKT out from under us. It was awesome. Not exactly out of nowhere, since Jon and I had climbed Yellow Spur plenty of times together while I worked out my kinks, it was still a bit of a surprise. Who the hell is this Nodin guy, anyway? He jumped in from obscurity and crushed! For the next week, our two teams swapped successes, until Jon and Nodin carried the time down to 46m55s. Productivity ground to a halt in all other areas of life. I had separate conversations with Bill and Jon daily to discuss minutia. “oh, we don’t clip that pin”. “No man, twist onto your palm and mantle to that jug, left foot stemmed onto that dimple”. “Hey, you don’t have to tell me, if I could rename my firstborn after that finger lock somehow, I would.”

So there we were, sitting on my tailgate. The sun was up now, and it was time to give it another shot. Jon was on hand too, just to watch and cheer us on. We wandered over toward the plaque at the center of the bridge, which marks the start and finish. My heart was pounding and we hadn’t even started. I hoped against what felt like slim odds to keep my breakfast down. Then we looked at each other, nodded, clicked our watches and took off sprinting. Down the trail, across the concrete pad, up the switchbacks, up the ladder, and scramble up to the base. I get there just ahead of Bill, and flake the rope. Our transition is a well timed symphony of teamwork. As he ties his shoes, I put gear on his harness, and when he stands up he just clips into the locker at the end of the rope and starts climbing. I have my Gri-Gri on by the time he’s at the first pin, then I belay him while I change into climbing shoes and tie in. As soon as my climbing shoes are on, Bill is yelling down “Micro!” and I start up. Focus and madness becomes me.

There is about 6 feet of rope below my Gri-Gri and as I climb the first three pitches I balance the management of slack with the gear I am collecting and the climb itself. Bill is above trying like hell to take all the rope from me and we battle this way; locked in a game of tug-of-war in which no tugging is allowed. I have gained a sense of when he will need rope, and give it out as I climb. Then I collect it back when I can. At the red ledge I clean gear and wander through pitch four. I am on easy terrain but Bill approaches the slowest part of the route, the pin ladder. Soon I’m into the hand traverse, and now the madness creeps back in. I scamper up above the slot, to where I can fully see Bill above me, and he yells down “micro!” one last time signaling safe(er) passage.

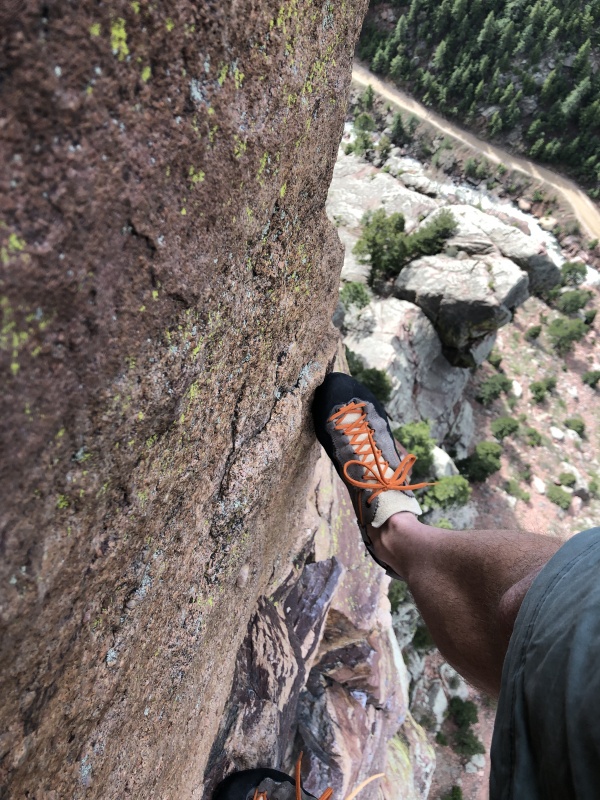

This next pitch remains the one part of the route that I can’t climb fast. But damn, what a rad pitch.

After I clean the last micro I’m aware now that falling would have serious consequences so I take my (relative) time. On to the final pitch 6 arete, and when I top out I yell down to Bill “slack!”. I untie, grab the wad of gear and pull the rope through everything. “Take!” Bill pulls the rope in and by the time I scramble down to him, he’s backpacked the rope and changed shoes. He says the same thing he says every time “be safe, no mistakes” and then takes off running. I frantically change shoes, and follow suit. We sprint down the east slabs, and I do mean sprint. I’ve got cams and slings jingling and swinging all over, sweat dripping from my helmet and fire spewing from my shoes.

Back to the bridge in 42m48s round trip for a new FKT.

Then things go calm. Jon and Nodin lose interest, so Bill and I do too. Sort of. We still love the route, and so we climb it almost weekly for about two years in a pretty similar style to the speed climb. We take turns leading it, and over time I become capable of leading it as fast as Bill just as he becomes adept with the rope management below. We rack up ascent after ascent without looking at our watch, and often just as a fun way to get back to the parking lot after climbing on something else.

Then one morning, Bill asks if I would be up for doing it under an hour again. Of course I am, and Bill leads us through a 50m21s Bridge to Bridge lap without much effort. It might’ve stopped there, if not for those extra 21 seconds at the end. Three days later, I led us through a 43m22s lap. Very nearly the FKT again, and our fastest time ever on the route itself. Now we’re consumed again. We tweak the rack.

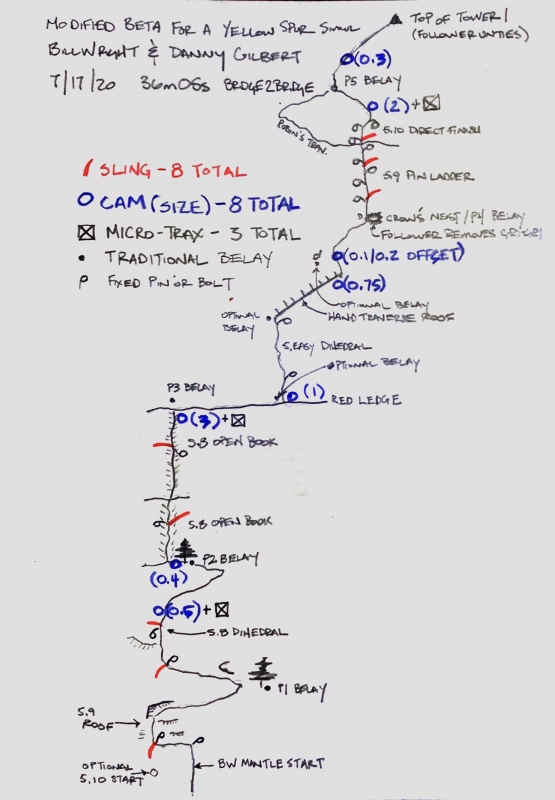

We put me up front, and alter our transition techniques accordingly. After a few more tries, with absolutely no stress or concerns we bring the time down to 36m05s Bridge to Bridge, shattering our old time.

We took additional risks to get it that fast. At some point we began using one less microtraxion (three instead of four). Over time we reduced our protection from 20 pieces to 16 pieces. We adopted a strategy on the first pitch which is best described as “the follower will just deck so it’s cool”. We transitioned from the 5.8 finish to the 5.10 finish. We appear to have grown more and more insane but all of those changes were born out of climbing the route for fun, not for time. An honest assessment of risk needs to consider the most important variable: the climber. We became better at climbing the route. How many times do you need to travel through a climb before you have it figured out? The answer, it has begun to seem, is never and I can’t wait to climb it again. Local legend Max Manson made a short film about our FKT: |

| Comments or Questions | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Caution: The information contained in this report may not be accurate and should not be the only resource used in preparation for your climb. Failure to have the necessary experience, physical conditioning, supplies or equipment can result in injury or death. 14ers.com and the author(s) of this report provide no warranties, either express or implied, that the information provided is accurate or reliable. By using the information provided, you agree to indemnify and hold harmless 14ers.com and the report author(s) with respect to any claims and demands against them, including any attorney fees and expenses. Please read the 14ers.com Safety and Disclaimer pages for more information.

Please respect private property: 14ers.com supports the rights of private landowners to determine how and by whom their land will be used. In Colorado, it is your responsibility to determine if land is private and to obtain the appropriate permission before entering the property.