| Report Type | Full |

| Peak(s) |

Chiefs Head Peak - 13,577 feet |

| Date Posted | 03/17/2019 |

| Date Climbed | 08/15/2002 |

| Author | flyingmagpie |

| Climbing Chief's Head Peak |

|---|

|

Though McHenry’s Peak only offers one difficult Class 3 scramble to its summit, Chief’s Head offers two good Class 2 scrambles, and one Class 3. I have had some experience on all three approaches to Chief’s Head. The Class 3 route is up the Northwest Ridge, which runs from Stone Man Pass just like the McHenry’s route does. I was already familiar with Stone Man Pass because I had just climbed McHenry’s, so I chose that route to first climb Chief’s Head Peak the same month, August 2002. For some reason I no longer remember, maybe because I didn’t think I had taken enough good photographs on my first climb, I turned right around and repeated the Chief’s Head again that August before I moved on to next climbing Copeland, Alice (via Boulder-Grand Pass), Ogallala, and Powell the same month. I think I had just retired in July from the State of Colorado and no longer worked weekdays at my full-time job in the Norlin Library on the CU-Boulder campus. In August I could finally climb and hike any day of the week I felt like it. And, avid hiker and climber that I am at heart, I seem to have felt like doing that often. But to get back to the two Class 2 routes up Chief’s Head, one is via the West Ridge, the ridge that Gerry Roach calls the “Hourglass” because the otherwise broad ridge narrows at one point in the middle. Lynn Prebble and I climbed up to this ridge on a wonderful warm autumn day in October, 2003, and though we did not Climb Chief’s Head from there, we climbed Alice. The second is up the Southeast Ridge of Chief’s Head, which on maps bears the enigmatic name of the “North Ridge,” though it is not such a thing to any mountain whatsoever. It is however, the Northwest Ridge of Mount Orton, a modest 11er, which I have climbed several times simply to take photographs from that beautiful perspective it offers across Wild Basin of the photogenic back side of Longs Peak. Let me share you my favorite photograph of Longs from this perspective, which is not often shared. It is the East side and the dramatic Diamond Face most people call to mind when they think of Longs.

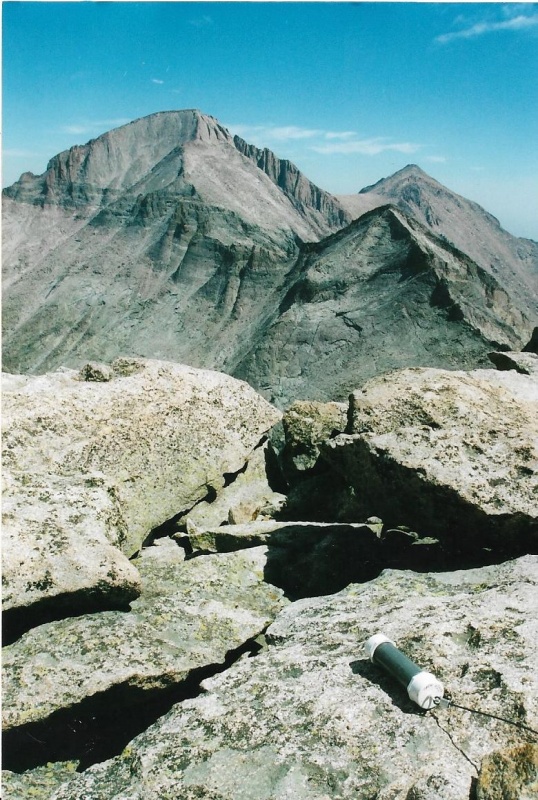

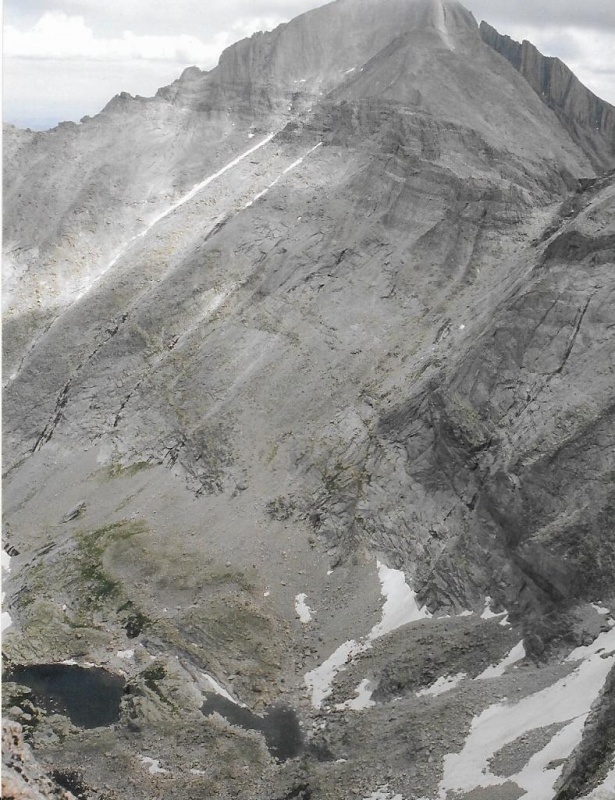

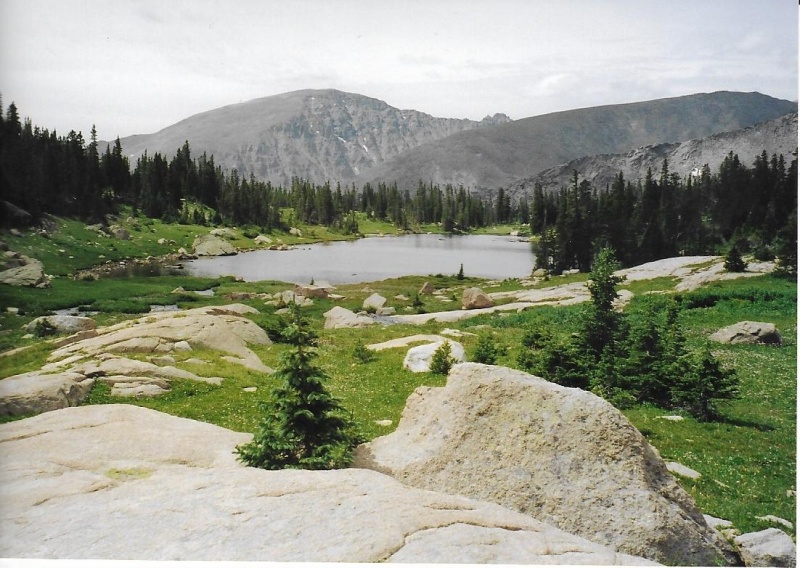

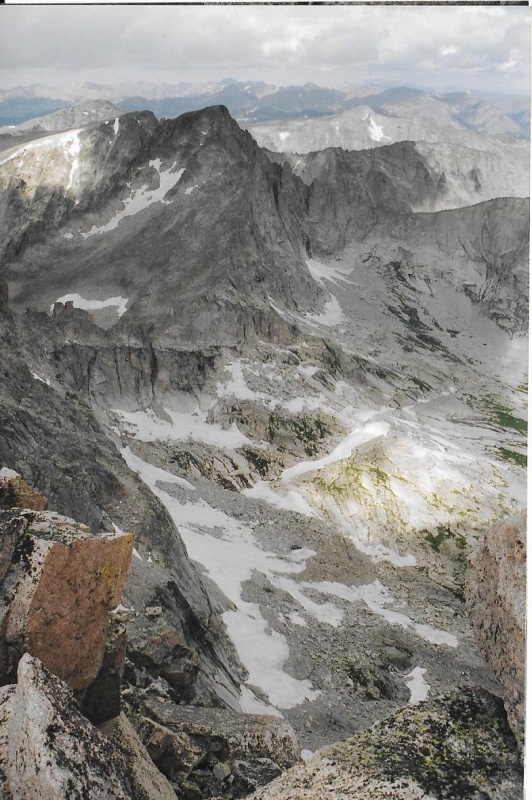

There is quite a history to this back side of Longs, as some of you might not yet know. The couloir clearly visible between the main bulk of Longs itself and the point commonly called the snout of the Beaver is named “Keplinger’s Couloir,” and that is the route by which the first successful climb of Longs in written history was accomplished. Prior summits of the mountain by Native Americans to capture eagles for their feathers were not recorded until later. The first recorded attempt to climb Longs was made by William N. Byers, who had been a prominent Nebraska settler, and who helped found Omaha. After the Colorado Gold Rush and the growth of Denver, Byers realized there was a need for a newspaper in Denver, and moved there and founded Denver’s now unfortunately defunct “Rocky Mountain News.” Byers was an outdoorsman, and fit right into the area well. He traveled and climbed mountains. He and another man made a couple of good attempts to climb Longs using two different routes, but they failed to summit either attempt. Byers used the forum of his newspaper to pronounce Longs Peak unclimbable. Well, you know what usually happens when some reliable prominent citizen claims something simply can’t be done? Some daring, uppity whippersnapper takes that as a personal challenge, and just goes out and does it. On Longs Peak, that daring, uppity whippersnapper was none other than the remarkable John Wesley Powell. John Wesley Powell is well-remembered, and justly so. Powell is a model of determination and true grit. He was handicapped by the loss of one arm. He lost it during a battle in the Civil War, in which he served as a Union officer. At the battle of Shiloh, it is told, he raised his arm to give the order for his soldiers to fire, and when he did so, that arm was immediately shot right off by Confederate fire. Both before and after the war, Powell accomplished a number of remarkable things. I need only mention here that he is given credit for leading the first recorded, civilized boat trip through the entire Grand Canyon, and that he led the first group of climbers to successfully summit Longs Peak. They did so from a high camp believed to have been near Sandbeach Lake. There was a young climber in the group who was pretty darn good at route finding. He scouted the mountain, and discovered the couloir on the back side of Longs and in my photograph. That couloir is now named for him. He returned to camp, and told Powell he thought he had spotted a good route by which Longs could be climbed. And the following day Powell’s party of climbers set out early, and then did just that. Ironically, W.N. Byers, who had said that Longs could not be climbed, got wind of what was up, and joined the Powell party. On this his third attempt to climb Longs, with Powell, he succeeded, and finally stood on the summit himself. Those of us who have climbed Longs by the Clark’s Arrow Route know that the route crosses Keplinger’s Couloir high on the peak. On the far side of the couloir, climbing higher, we are confronted by a dome of rock resembling a bald human forehead. It usually has a band of snow across its top dividing it from the southwest face proper. I think it is likely that Powell’s group, led by Keplinger’s route-finding skills, finished Longs with the same finish we now use—we cross above the dome of rock to what is now called the Home Stretch, and scramble to the summit up those cracks. The dome of rock is one of the Clark’s Arrow Route’s many cruxes. If the dome is icy or wet, it is dangerous, and you must find another way to reach the Home Stretch. If your feet went out from you on the dome, and you began to slide, you would slide down the entirety of it, a fall that would probably break bones or cause other serious injuries. But, to get back to Chief’s Head. I have climbed Chief’s Head by two of its available scrambles, first climbing the Class 3 route across Stone Man Pass twice in August, 2002, and later up the North Ridge in August, 2004 from Wild Basin. I didn’t gain the North Ridge via the shortest, easiest way over Mt. Orton from the Copeland Lake Parking Area. I gained it up a longer approach that began from the regular Wild Basin Trailhead further south. I was photographing the Park’s waterfalls as well as climbing that year. And I wanted to photograph Trio Falls, which is located between the two Lion Lakes. I had never seen Trio before. After photographing the Falls, I climbed above Trio, and gained the North Ridge from there. I descended by retracing the same route I had ascended, following it back out to the Wild Basin Trailhead where I had parked my truck. At any rate, there are two parts to this trip report. The first covers my first and second ascents of Chief’s Head via Stone Man Pass. Photographs from both climbs are included, and the weather and sky were nearly identical on those August climbs. This will be the short first part of report, because I will only go over the route from Stone Man Pass up to the summit. If you want to review the route to Stone Man, you can just refer back to my prior trip report on McHenry’s Peak, which I climbed via Stone Man as well. The second part covers my 2004 ascent of Chief’s Head from Wild Basin via the North Ridge Route. This second part will be much longer than the first. Part One: Chief’s Head via Stone Man Pass As usual, my Introduction to this part will wander way off the subject at hand. I first want to share with you three photos I found of my Chief's Head climb via Stone Man that provide better views of certain specific things I mentioned in my McHenry’s trip report. The first photo I want to share provides a better view of the Class 3 route up Spearhead that I told you was described by Gerry Roach in his RMNP climbing guide. This is a better view of the ascent scree gully over Frozen Lake on the way to Stone Man Pass. And that is Chief’s Head Peak, the subject of this trip report, over Spearhead. Roach writes that the best route to the summit from the ridge line is the west side. That is the side in this photo. He advises to stay “well below” the ridge crest, and to dodge small cliffs along the way to the top.

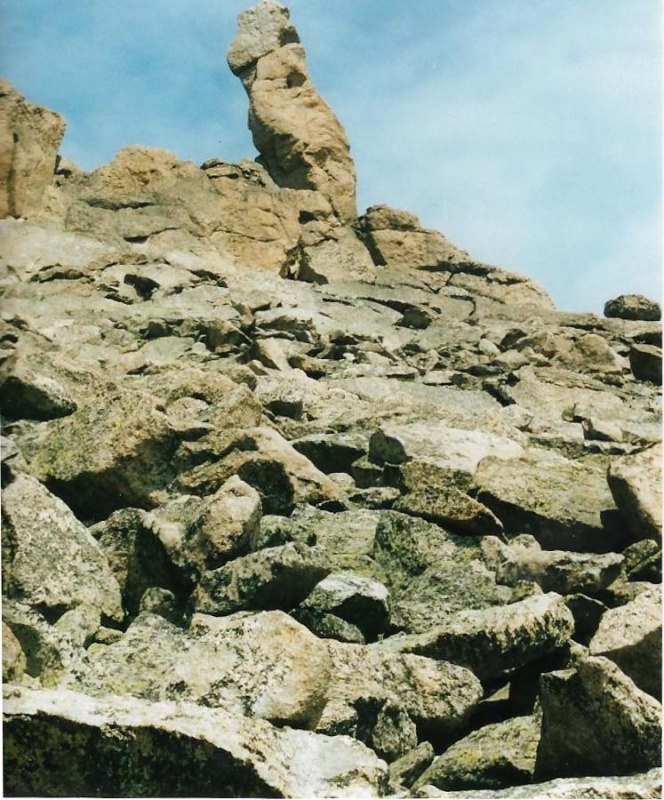

The second photo was taken past Frozen Lake and on the way to Stone Man. It provides a better view of what the Stone Man looks like on the ridge line on your approach to the Pass, which is out of view just below the lowest point on McHenry’s ridge line left of center.

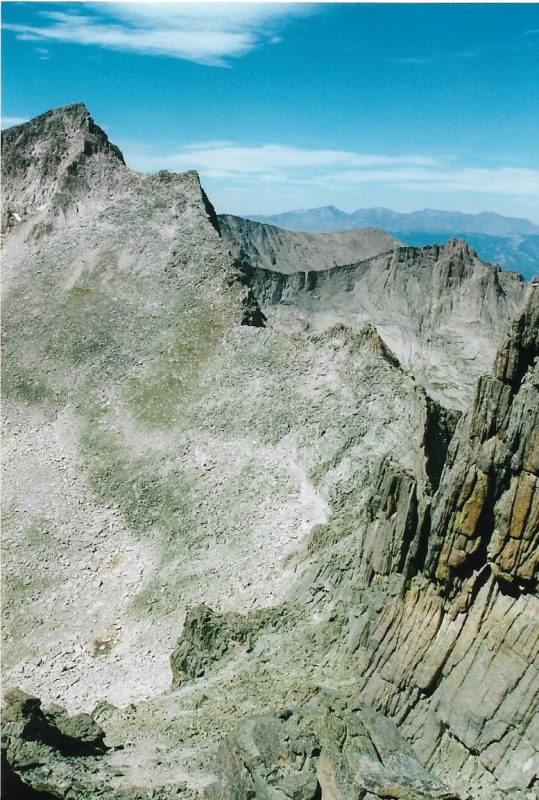

I share the third photo with you because it shows three important things. The first is the great west face of Pagoda Peak and the circling ridges below it, just left of center. Deep at the bottom of this west face, and so not showing in this photo but there just the same, lies Keplinger Lake, another landscape feature named for the skilled route-finder on Powell’s expedition.

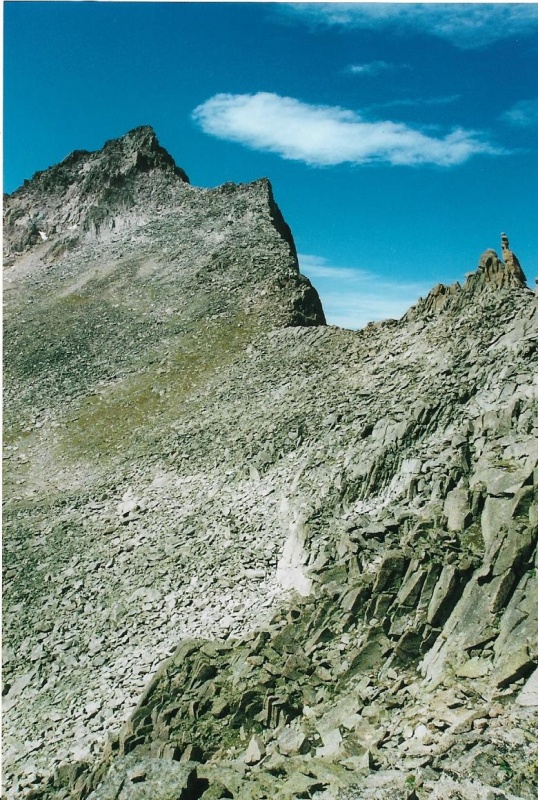

just left of Meeker's southwest ridge was my turnaround point in Wild Basin on my first two attempts to climb Meeker. Aborted the climbs there both times. Meeker seems overwhelmingly huge and as big as the whole world from that little knoll. Now back to climbing Chief’s Head from Stone Man Pass, beginning from the other side of the Pass just below the Stone Man. This is a review of my photo from my McHenry’s trip report which shows you the ascent gully ahead passing through the rock pinnacles to the northwest ridge line of Chief’s Head which is also visible. There is a cliff face in the photo just right of center bottom that you must pass below to then begin to climb toward the ascent gully.

I think I will just let these pictures show you the way without adding text, just using captions to the photos to do so.

Pass in this photo. It is tight up against some cliffs directly below McHenry's summit. The low point on the ridge line is a bit farther right.

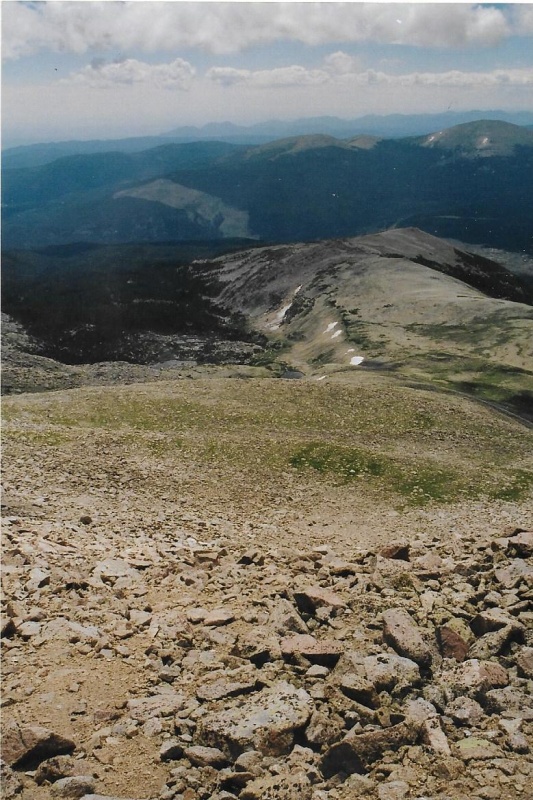

View of The North Ridge Proper, and Orton Itself. Clearly Visible in the Distance is the Burn Scar From the 1978 Ouzel Forest Fire, Which Was Making A Wind-Driven Dash Toward Allenspark before it Was Finally Contained. Significant Regrowth of the Forest Has Occurred Since This Photo Was Taken in 2002.

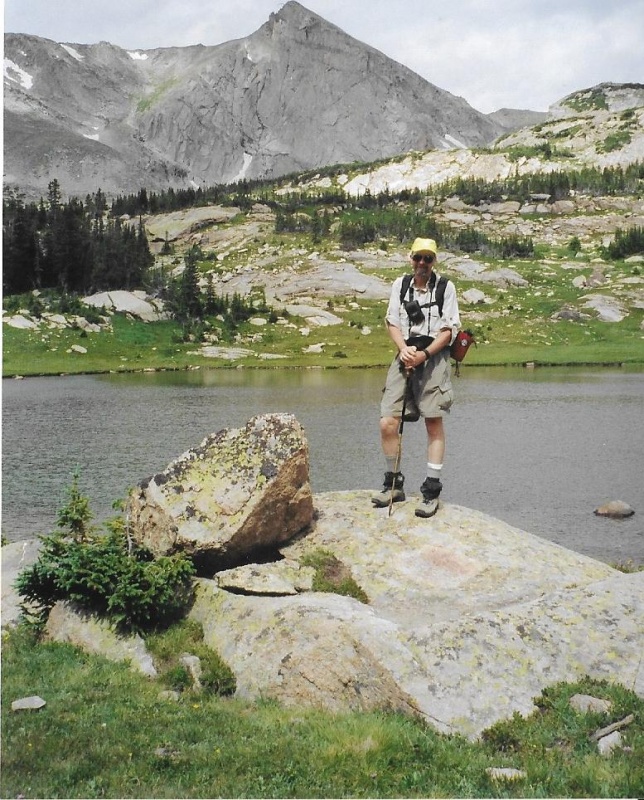

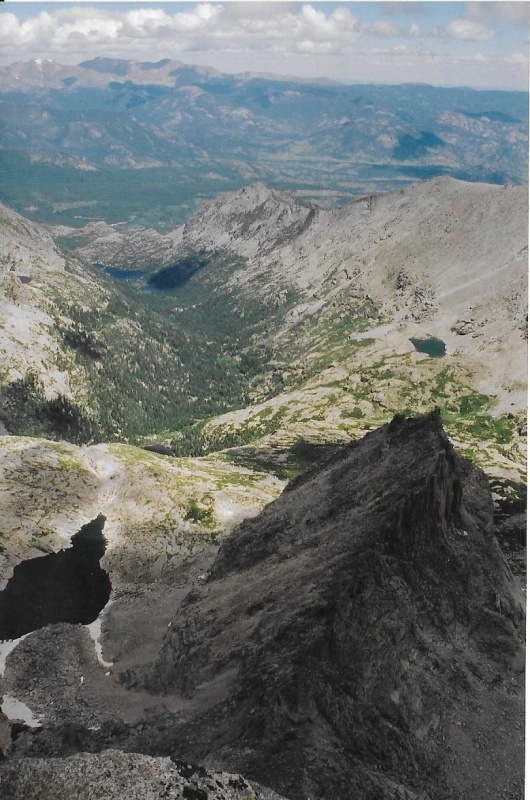

Part Two: Chief’s Head via the North Ridge The closest approach to the North Ridge begins at the Sandbeach Lake trailhead. There is a back country camp site at Sandbeach Lake if you want to break this long hike into two shorter hikes with an overnight. Chief’s Head is about 7 miles from the Sandbeach Lake Trailhead if you want to do this as a day hike, which totals a 14-mile round trip. I have climbed Mt. Orton from this trailhead, but not Chief’s Head. I climbed Chief’s Head via the North Ridge Route from the main Wild Basin Trailhead because I wanted to also photograph Trio Falls, which is between Lion Lakes 1 and 2. The second Lion Lake is about 7 ½ miles from the Wild Basin Trailhead. The climb up from Trio to the Ridge, and then to the summit might add another mile to that, so this is a long 17 mile hike if you want to do it in a day. I will begin this trip report from the Lowest Lion Lake. A Park topo map and trail signs should guide you from the Wild Basin Trailhead to Lion Lakes. Stay on the main Wild Basin Trail. I would advise you not to take the turnoff to Calypso Cascades and Ouzel Falls even if you haven’t seen them. Your hike will be difficult and long enough without adding extra distance to it. If you want to break this down into two hikes, there are 5 back country campsites along the trail on the way by which you can do so. After the last campsite there is a significant trail junction. You don’t want to take the left turn to Thunder Lake. The trail to the right takes you to Lion Lakes. Lion Lakes are surrounded by beautiful meadows. This is a great wildflower hike.

Guard Prior to This Hike. Note the Graying Goatee.

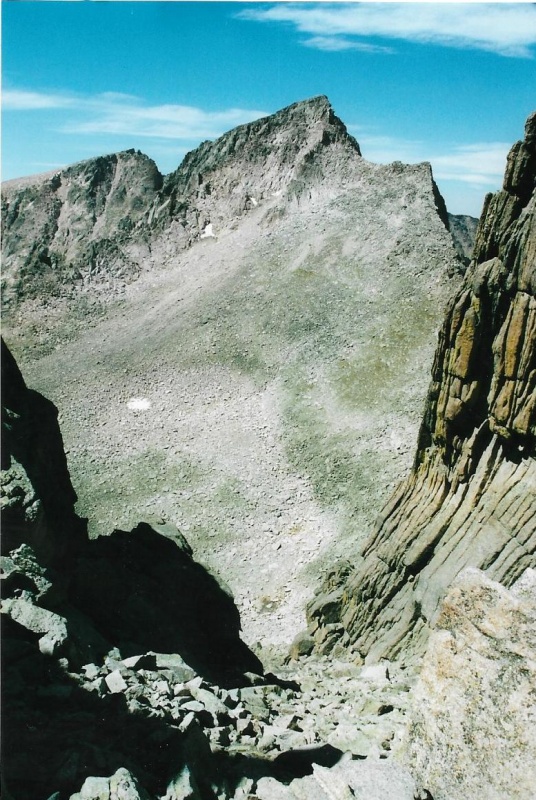

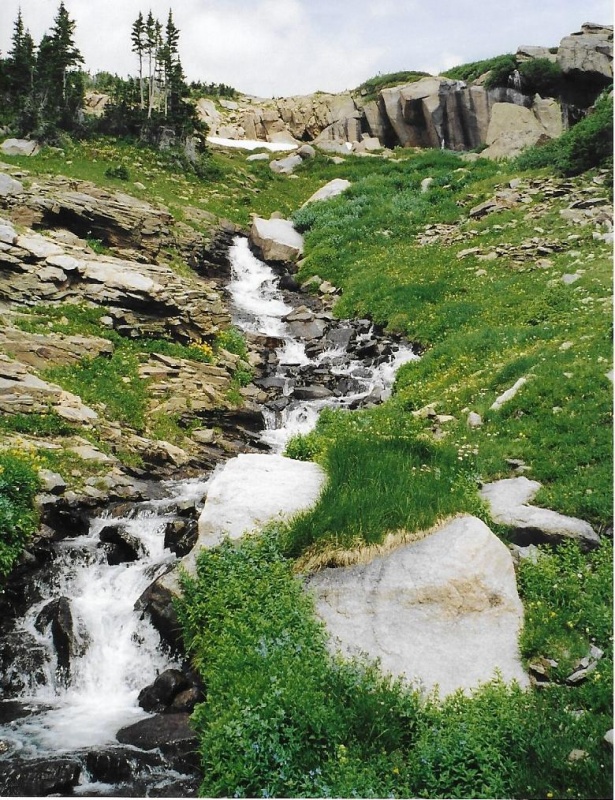

Trio Falls is a bit above the trail. I followed the creek that flows from it on up to the Falls. The cliffs of the Falls break the creek above into three separate plunges of water. Hike above the cliffs and study them for a moment to pick what seems to you the best route by which to gain the ridge. There are many choices. Then begin climbing the north ridge to the summit of Chief’s Head. It is not a steep climb, but it is a long one! You should be able to gain the summit without a significant obstacle or problem. The summit offers terrific views in all directions. The summit is a bit unnerving, however, because to get to the edge with the best views, you have to step over a narrow crack that runs along and parallel to the great stone face of the peak. The crack goes very deep, and you can’t see any end to it. I always wonder, “What if the weight of my body is just enough to widen this crack and then break this huge granite flake from the face?” For some reason, I always worry, even though I have stepped across the crack three times now without any such thing happening. The flake seems pretty firmly attached, and has survived untold centuries of freeze-thaw cycles.

Ridge Would Be the Best Side to Use to Climb Spearhead. Just Look at That Summit! Whoowee! Mummy Range Peaks Upper Left are Fairchild, Hague's, and Mummy.

Since this is a wildflower climb past Lion Lake Number 1, I thought I would end this trip report with a close-up of red Indian Paintbrush, and one of my favorite photos of Mt. Alice in the fall, and Lion Lake Number 1.

Scanner's Glass. |

| Comments or Questions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Caution: The information contained in this report may not be accurate and should not be the only resource used in preparation for your climb. Failure to have the necessary experience, physical conditioning, supplies or equipment can result in injury or death. 14ers.com and the author(s) of this report provide no warranties, either express or implied, that the information provided is accurate or reliable. By using the information provided, you agree to indemnify and hold harmless 14ers.com and the report author(s) with respect to any claims and demands against them, including any attorney fees and expenses. Please read the 14ers.com Safety and Disclaimer pages for more information.

Please respect private property: 14ers.com supports the rights of private landowners to determine how and by whom their land will be used. In Colorado, it is your responsibility to determine if land is private and to obtain the appropriate permission before entering the property.