| Report Type | Full |

| Peak(s) |

Storm Peak - 13,323 feet |

| Date Posted | 02/18/2019 |

| Modified | 02/22/2019 |

| Date Climbed | 07/15/2001 |

| Author | flyingmagpie |

| Climbing Mount Lady Washington and Storm Peak |

|---|

|

For me, 2001 was a year of accomplishment, and learning. For example, I had recently bought a pair of crampons and an ice axe, and I was learning to use them. In June that year, I carried both in my pack up to the Boulder Field, and then to the Keyhole, though I didn’t climb through it. My goal was actually the “Dove,” a long narrow snowfield beneath Longs’ great North Face. In certain snow conditions and times of year, the snowfield resembles a flying dove, its tail near the Keyhole and its body and beak reaching south below cliffs toward Chasm View. One of its wings is raised above, the other dropped below its body. This photo was taken on a climb of Longs in July or August of 2002, and I include it here just to show you that the snowfield does indeed sometimes resemble a dove.

On this day very early in the climbing season, the first week of June, a lot of snow was still left up high. Snowmelt was going on, and a lot of icy water was running down the North Face, and funneling down the crack systems that broke through a steep cliff-like face that barred easy access to its gentler terrain above. The Dove was much larger than it is in the summer photo above. In fact, the Dove looked nothing like a dove at all, and stretched all the way from the Keyhole to Chasm view.

To make a long story short, when I reached the long, broad snowfield near the Keyhole that didn’t really resemble anything at all, I sat down on a bare rock, took off my pack, and removed my new crampons and ice axe from it. I put my crampons onto my boots, and, re-shouldering my pack, picked up my ice axe and walked across the Dove from its Keyhole beginning to its Chasm view ending. After doing that, I turned around and looked back at my tracks. Wow. My first use of crampons! It felt clumsy and awkward, but I hadn’t fallen or slipped. After I looked at my tracks, I turned again and stood there for a while longer, studying the great the North Face directly above me. Another climber I hadn’t even noticed nearby came up behind my back and startled me with his sudden voice. “I think we can do it,” he said. I turned around to face him. “Do what?” I asked innocently. “Climb the North Face,” he said. “I think enough snow has melted now that we can do it.” This was Sam Crater. I would only learn his name later on our climb together. I looked back up at the Face. “Sure, why not?” I answered, happy to have some company on yet another experience that would be new to me. The last time I had climbed the North Face, in 1969, I had only done so via the cables, which were now gone. This would have to be a free-climb. I didn’t have a clue what I was getting into. I was completely ignorant. That is the only reason I agreed so easily. “Pick your crack,” Sam said. All the cracks were running icy snowmelt water. I already knew which crack I wanted. I wanted the one that wasn’t just a crack. It was wide in places. I had climbed up that broad channel over thirty years before, in 1969, with the aid of the lowest cable. I remembered that, though the cable was now gone, the eyebolts were still there, and could certainly be a help to me. “You go ahead and start up,” Sam said. “I’ll catch up with you as soon as I get my climbing shoes on.” I should have realized right then what I was getting myself into. He dropped his pack, took out a pair of soft-rubber soled climbing shoes, and started taking off his boots. “Go ahead,” he urged. “I’ll choose another crack.” So, I started up, all right. I was still wearing my new crampons. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was using an actual climbing technique called “dry-pointing.” I was using crampons not on snow, but on hard rock. Soon, I was high enough that I knew I couldn’t turn back. I was wedging my boot and knee between opposite sides of that broad channel. I was holding onto to any handhold I could grope with my free hand. My other hand, somewhat comically, still grasped the ice axe. I found a use for that, too. I guess you would call my climbing technique unconventional. Every once in a while, I would find myself stuck in a certain precarious situation where I could not find another secure hold on rock, or places to wedge my boot and knee. I was just stuck there. I would look up, and see an eyebolt above. The ice axe, tethered securely to my hand by a strap, added another three feet to the reach of my arm, so I would extend the axe to my furthest reach, hook the blade of the axe around that eyebolt, and with only that one secure point of contact (I should have had three), pull myself up to the eyebolt, wedge one boot against it, and from that one-booted stance, stand and rest for a bit. I could watch Sam below me, climbing up an adjacent nearby crack off to one side. We were both getting soaked by chilling snowmelt water. Getting soaked or not, we couldn’t let go of any secure hold or stance we were lucky to find. We just had to hold on for dear life, and let the cold water soak us. By this time, in my climbing development, I was wearing synthetic clothing, not cotton, and I knew it would dry quickly. That first 60 feet of steep bald-faced rock, broken only by cracks and my channel, was the worst part. I beat Sam to the top of that steep face. At the top, I found a little knob that was nearly level, and gladly stood on it. I took off my crampons, and put them into my pack. I put my ice axe through loops on the side of my pack. Sam was close behind. He looked up at me, from his holds, and called out. “Is that place where you are safe to stand?” he asked. “It is safe.” I answered. He finished his crack, and moved over carefully to my stance. We were on a pretty steep slope. I guess that is an understatement. Sam took off his climbing shoes, and put his boots back on. “Have you ever been up here before?” he asked. “Yes,” I answered. “Over thirty years ago, and I had cables to help me then. I’ll try to remember the way.” And we moved on carefully from there, and the route got easier, and soon it was Class 2, and after that we were on the summit pretty quickly. I couldn’t believe how suddenly glad and relieved I was. I had survived. Just lucky, I guess.

Lots of snow. We were the only ones up there. Rare. Longs was still technical. We opted to descend the standard Keyhole route, and did. That was our climb, that day, Sam Crater’s and mine. And I guess I would call it certainly memorable. That, too, I guess is an understatement. As I said, 2001 was a year of accomplishment and learning for me. I never repeated that all-too-lucky free-climb of the North Face. That was one thing I learned. Never to take that kind of a chance again.

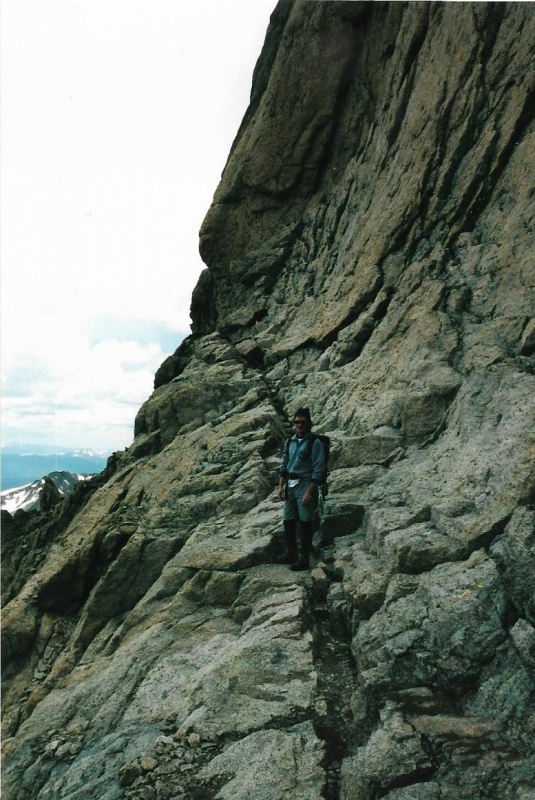

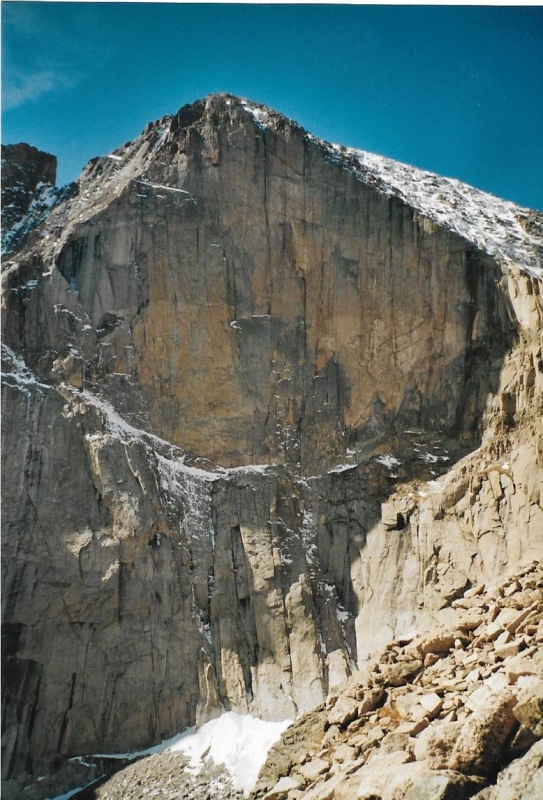

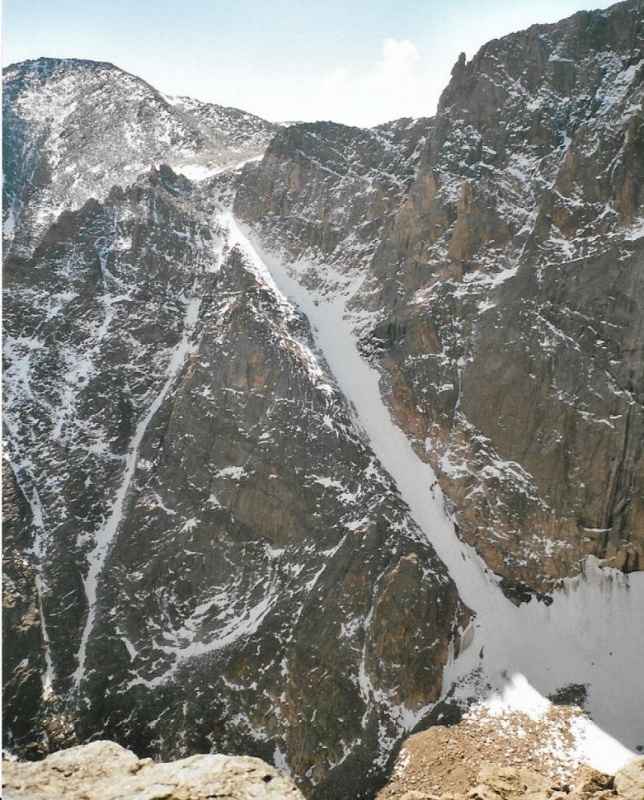

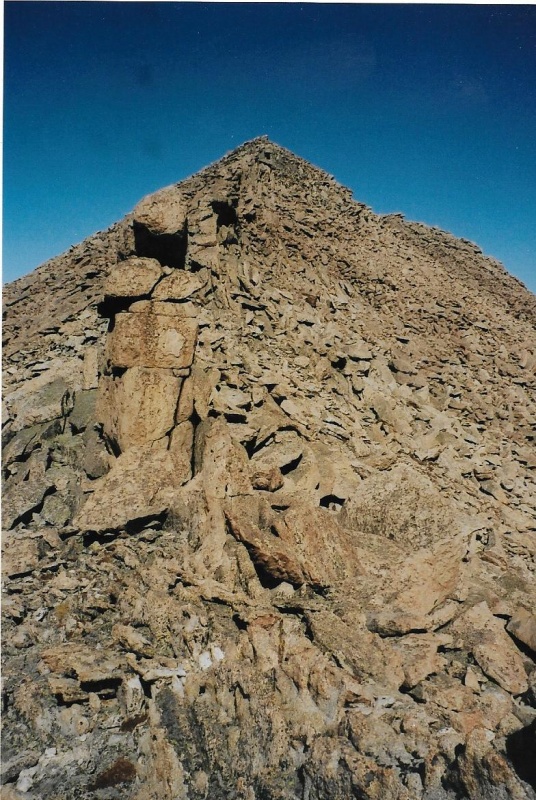

Sam--I hope you are still out there, somewhere, and if you are, I would like to offer you my thanks, much deserved but belated, for all that I gained from your quiet company on this climb, and our subsequent safe descent, especially the confidence I gained in my own climbing ability through climbing with you. That confidence has gotten me safely through all my subsequent years of climbing, so far, anyway. I hope I continue to climb, and to you I offer the climber's salute: "Climb on!" I wanted to climb the North Face of Longs. But I didn't have the courage to do it alone, solo. Climb on, climb on, Sam, wherever you journey. Another accomplishment and learning experience for me in 2001 was climbing Mount Lady Washington and Storm Peak, the mountains that rise up to the southeast and northwest, respectively, from the Boulder Field. I had climbed to the Boulder Field many times already on my climbs of Longs. I wanted to climb these two peaks a different way, via the Kneeling Camel Route. I had heard about this route from Rangers whom I knew. They said they used the route as a shortcut from Chasm Lake to the Boulder field, and vice versa. I knew the route was there. I just had to find it. The key to the route was finding the ascent couloir that climbed from Chasm Lake to the shoulder of Lady Washington. I had taken a photo of Lady Washington below when I had crossed high on the North Face on my climb with Sam Crater. I thought I could see the top part of this couloir on the photo. I showed the photo to a Ranger I knew, and asked him if it showed the top of the couloir. “That’s it!” he had said. Now that I knew where the couloir ended on Lady Washington, I just had to find out where it started near Chasm Lake. One early morning in July of 2001 I set out to do just that, and to climb the two 13ers.   The two photos above were taken from the North Face high above the Boulder Field. The top photo is of Mount Lady Washington. The end of the ascent couloir from Chasm Lake is at lower right, near the corner. The bottom photo is of Storm Peak. The ridge-line routes you must climb on each peak, and the false summits of each, are clearly visible. The true summit of each peak is its easternmost point. To get to Chasm Lake, I first hiked up the Longs Peak trail to Chasm Junction, and then Chasm Meadow. From the Old Chasm Meadow Patrol Cabin, I hiked up a band of easy cliffs polished smooth by glaciers centuries ago.. There is a nice little cascade below the lake. I am going to combine photographs from four or five of my climbs during different seasons up the Kneeling Camel Route. I have climbed the route many times, because it saves miles.

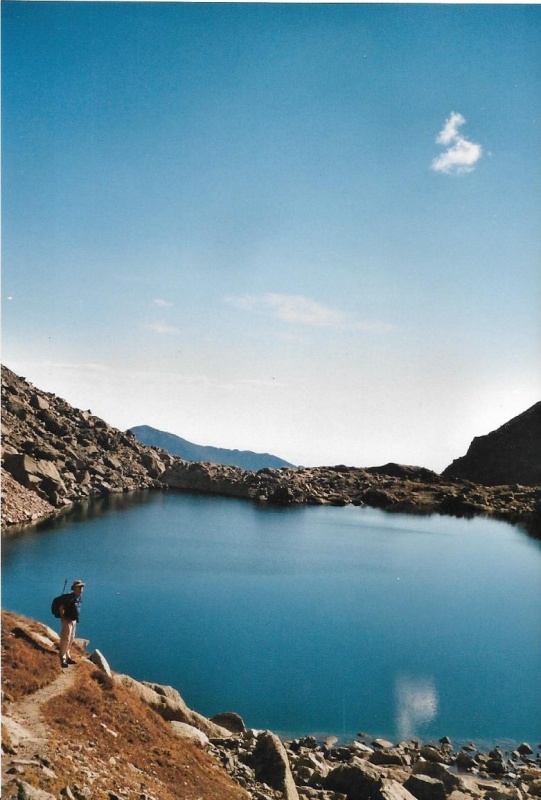

There is a trail that passes around the right, or northern, side of Chasm Lake. Above this side, the slopes of Lady Washington rise. Mount Meeker’s slopes rise above the left, or southern side of the lake. The trail is rocky, and in many places only marked by cairns.

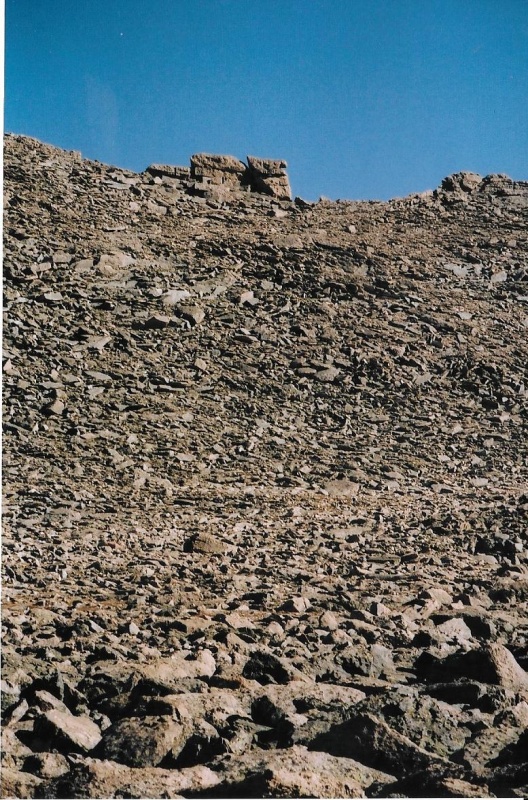

I had to hike all the way around the lake, until further passage was blocked by some cliffs. I had to hike up a little grassy slope to reach the bottom of the couloir I wanted to climb, and only then, below the cliffs could I look up and see the entirety of the couloir. Find the couloir, and the rest of the route follows routinely. There are some landmarks to help you recognize the couloir. One of the landmarks is a persistent snowfield that lingers all summer, most years. Another give-away is the broadness of the couloir. It is a rocky highway to the sky, really. Earlier couloirs that might have fooled you are not so wide. Thirdly, the couloir reaches all the way to blue sky. From its bottom, you can see up all the way almost to its end.

When you get to the end, you need to turn left, and keep climbing up talus. The rocks gradually get bigger. To locate the couloir again on your descent (if you want to descend the way you came up), aim toward Chasm Lake from the formation called the Kneeling Camel, which gives its name to the route.

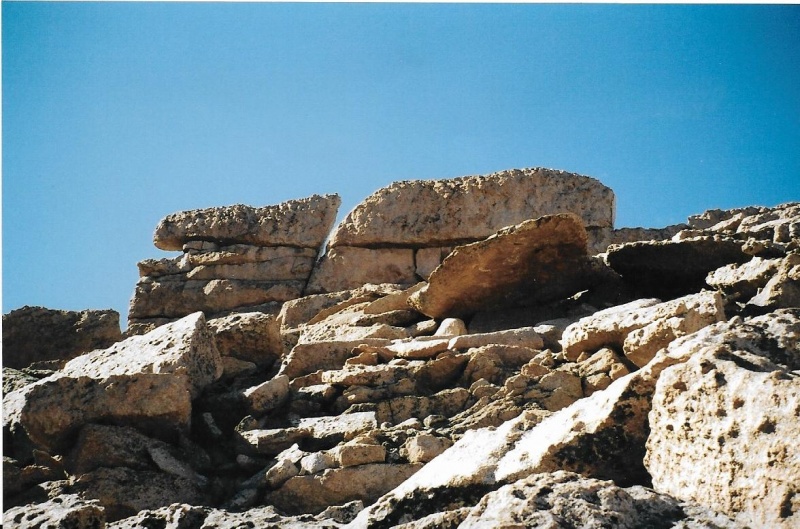

As you continue to climb left, you are looking for a pair of cliffs, one above the other, with an easy talus field passing between them. At this point you can see the very top of the Camel above, silhouetted against the skyline. Hike the talus field between the cliffs, and then just rock-hop up big boulders to the ridgeline near the Camel. There are some awesome views along this way—the Diamond Face and Broadway on Longs, and Lamb’s Slide, a broad snow-filled couloir which has to be climbed with crampons to reach Broadway.

The head and the hump of the Kneeling Camel sre at skyline, center.

Lamb’s slide, if you haven’t heard the story, is named after Elkanah Lamb, a preacher who was one of the earliest homesteaders who settled in the Tahosa Valley, on a beautiful piece of land at the very northern end of the valley, with a fine view looking down at the Estes Valley below. “Mountain Home,” he named it. Lamb was the first to climb the couloir named after him, and slipped at the very top, beginning an unplanned and perilous ever-accelerating glissade that would have killed him if he hadn’t miraculously managed to self -arrest with the blade of his pocket knife.

After quite a bit of rock-hopping, you come to the Camel, and the ridgeline.

From the ridgeline, you must turn right, and start climbing up a steep slope, picking whichever side of the slope you think would go easiest. Some pinnacles along the way block easy passage along the ridgeline itself.

After that first steep slope, the climb begins to ease. There is one false summit near the very top, separated by a little saddle from the true summit furthest east. Though my climbing buddy Randy and I found a register on the summit in our climb of the route in 2005, I didn’t find one this climb, though it was probably there. There is a rock on which you can stand on the southern slope of Lady Washington that appears to be a teeter-totter with a bit of air beneath. The rock provides a fine view of the Diamond Face. Just like many others, I have had my photo taken on the teeter-totter, which is actually quite stable. It doesn’t teeter at all.

From its summit, Lady Washington provides a fine view of Storm Peak across the way. The summit of Storm, just like Lady Washington, is the very easternmost high point of the mountain. The best way to get there, I believe, is not to cross summit to summit, but to return to the Camel and cross the Boulder Field where it is narrowest and highest near Chasm View, aiming straight for the Keyhole.

The true summit of Storm is far right.

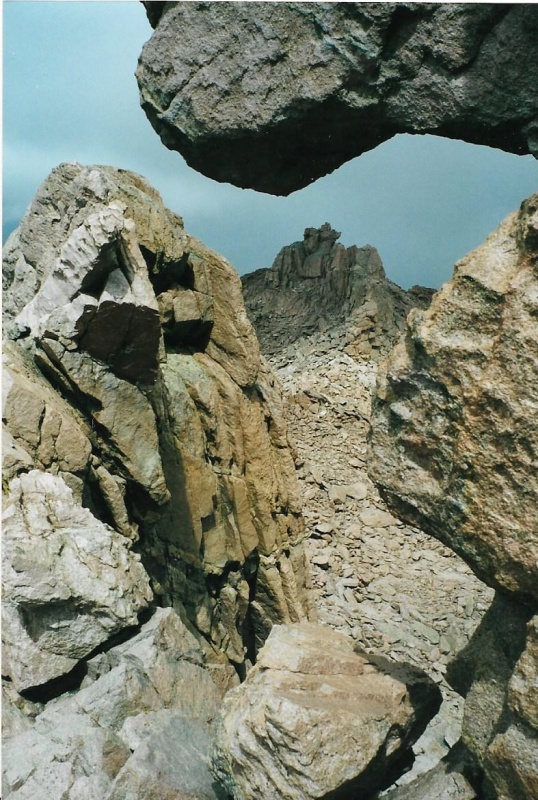

On this, my first climb of the two peaks together, when I reached the Keyhole, I stepped through it to take a photo of Storm’s ridgeline through the opening.

Only then did I cross back, and begin to climb the ridge. It is a long ridge, but I eventually reached the summit.

Late in the season on my second climb of Storm, the Dove has mostly melted. I don’t remember if I found the summit register on Storm that day, but I sure found one on my second climb of Storm another year, and later in the climbing season. After I had topped out on Storm, I definitely didn’t want to do any more rock-hopping than I absolutely needed to do to get down. I chose to descend via the longer and gentler standard trail from the Boulder Field. I wanted tundra and grass, no more rocks. The descending trail turns right at Granite Pass and then descends the East Longs Peak Trail, then turns left before Chasm Junction and takes the short-cut through Jim’s Grove, eventually (and that is a lengthy eventually) returning to the Longs Peak Trailhead and Parking Lot. I had climbed two of the Park’s 13ers for the first time that day! That was certainly an accomplishment! But on this particular day, with many miles hiked on the trails both in and out, and all the climbing of the peaks themselves, with much elevation first gained, then lost, then regained again, I was bone-tired. To be honest, I was dragging butt. My descent down the Longs Peak Trail was a weary road home for my beat-up body, though it was definitely also a soaring one for my soul. |

| Comments or Questions | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Caution: The information contained in this report may not be accurate and should not be the only resource used in preparation for your climb. Failure to have the necessary experience, physical conditioning, supplies or equipment can result in injury or death. 14ers.com and the author(s) of this report provide no warranties, either express or implied, that the information provided is accurate or reliable. By using the information provided, you agree to indemnify and hold harmless 14ers.com and the report author(s) with respect to any claims and demands against them, including any attorney fees and expenses. Please read the 14ers.com Safety and Disclaimer pages for more information.

Please respect private property: 14ers.com supports the rights of private landowners to determine how and by whom their land will be used. In Colorado, it is your responsibility to determine if land is private and to obtain the appropriate permission before entering the property.