| Report Type | Full |

| Peak(s) |

Mummy Mountain - 13,420 feet |

| Date Posted | 01/31/2019 |

| Modified | 02/09/2019 |

| Date Climbed | 11/15/1999 |

| Author | flyingmagpie |

| Climbing Mummy Mountain |

|---|

|

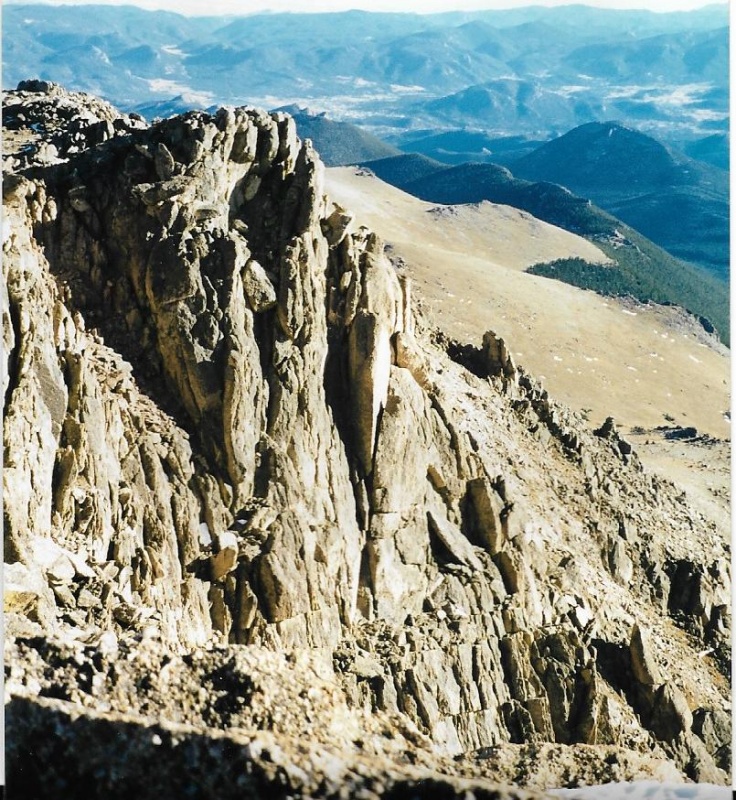

The weather held warm and almost snowless in Rocky Mountain National Park through the fall of 1999. After I had summitted Mount Meeker in September, I had continued to hike and explore trails in the Park, but I didn’t climb another Park 13er for over a month. Then, when November came and the mountains were still not snow-packed, I realized I should probably try to climb my second Park 13er. I chose Mummy Mountain in the range that bears the same name. It would be a very different climb than my climb of Meeker, I anticipated. Mummy is mostly a gentle, tundra-sloped mountain, except for its southwest side above Lawn Lake. The southwest side is rocky, steep and cliffy. I was not going to climb Mummy from that side. I told myself the easiest way to climb this mountain was to take the Lawn Lake Trail to the Black Canyon turnoff, then follow the turnoff until I thought Mummy Mountain’s southeast ridge had lost enough elevation to be easy to ascend. I would bushwhack through some timber, emerge from the trees at the base of the ridge, and try to spot a good place to cross the ridgeline to the grassy slope I expected to find on top. The most difficult thing about this climb, I believed, would be the elevation gain and the long approach, and that turned out to be the case. The Lawn Lake Trail’s intersection with the Black Canyon Trail looked to be a little less than 6 miles of steady elevation gain from the trailhead. Then, after the turnoff, I would be descending gradually for another 1 ½ or so miles, mostly losing elevation. The bushwhack and climb to the ridgeline would be a little less than a mile, gaining elevation again. Then I would have to regain over 2000 feet of elevation on the ridgeline climbing another maybe 1 ½ miles to the summit. So I was looking at a 10 mile hike with over 5000 feet of net elevation gain. I would be climbing a mountain nearly 13,500 feet high from a trailhead located at about 8500 feet. This would not be a short, easy hike. It would be my first 20 mile round-trip as a day-hike.I thought I was well-trained enough and had the endurance to pull it off, though. I had trained for and run a couple of marathons, 26.2 miles, earlier in the 1990’s, and had finished well. I had run many 5K’s, 10K’s and half-marathons. I could do this. Gerry Roach, in his book Rocky Mountain National Park:Classic Hikes and Climbs” suggests a shorter approach. He suggests engaging the mountain without descending at all on the Black Canyon Trail. He calls the climb the “South Slopes” climb, and says it is the shortest of any route for climbing the mountain and the best for a day hike. He suggests leaving the Black Canyon Trail shortly after it leaves the Lawn Lake Trail, at its highest point, before it begins to descend into Black Canyon and, ultimately, terminate at the McGraw Ranch Trailhead. His route engages the south slopes right at the very edge of Mummy’s steep, rocky, cliffy southwest side. It sure would provide a dramatic view of Lawn Lake below for the entire last mile of the climb. He calculates the distance of the South Slopes Route at 7.3 miles total, a little less than 15 miles round-trip, with 4,895 feet of gain. After my first ascent of Mummy in November of 1999, the one I describe here, I climbed Mummy for a second time in July of 2003. I think I climbed then by this shorter route Gerry Roach suggests, because when, even later than that, I inked in on my Park topo map the best route up Mummy for a friend (Lynn Prebble) who was headed off to climb Mummy and a few other Park 13ers, I inked in Gerry’s South Slopes Route. For my first ascent that I describe here, I wanted that south ridge to lose some elevation before I climbed up it to gain the crest of the ridge. Both routes go. My first route might be a little easier. South Slopes is definitely shorter.

Unlike my climb of Meeker, I did not think I needed to start hiking in the dark for this climb, and didn’t. I waited for first light and drove to the Lawn Lake trailhead, located off the very beginning of the old Fall River Road on the east side of the Park. The forecast was for a good, cool but not cold fall day in that lingering Indian Summer that year. There was little danger of sudden thunderstorms developing, or lightning. The days were growing shorter, but I thought the dawn start gave me plenty of time for both a successful ascent and descent before it got dark. The Lawn Lake trailhead was clearly marked, the trail well-traveled, well maintained and definite. I went through the usual ritual of sunscreen, and hydrating with fluid not carried within the water bottles in their pockets on my pack. I wanted to keep my bottles full until later on the trail. Then, layering up for the morning cold and shouldering my pack, I got going. The trail starts up through dense pine woods, but soon intersects the more open expanses of the Roaring River valley, and follows along the river. The results of a significant event that took place in the valley in 1982 and will probably remain dramatically evident for a long time became immediately and eminently apparent to me.

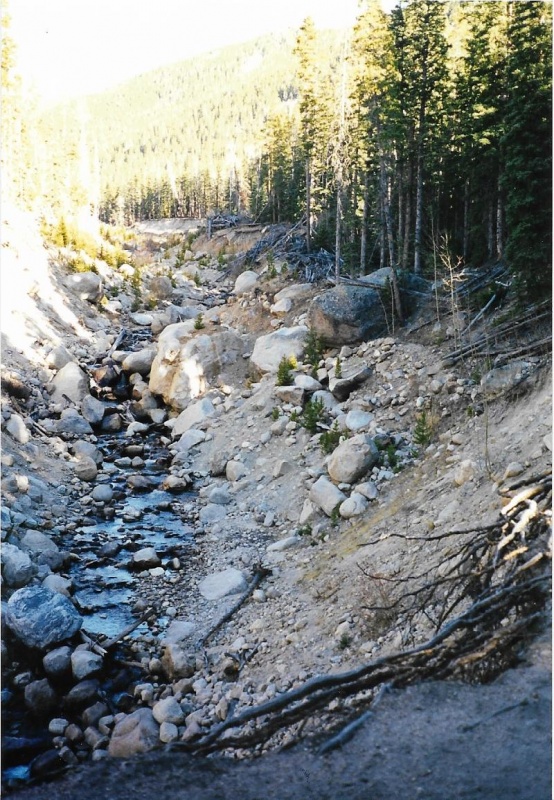

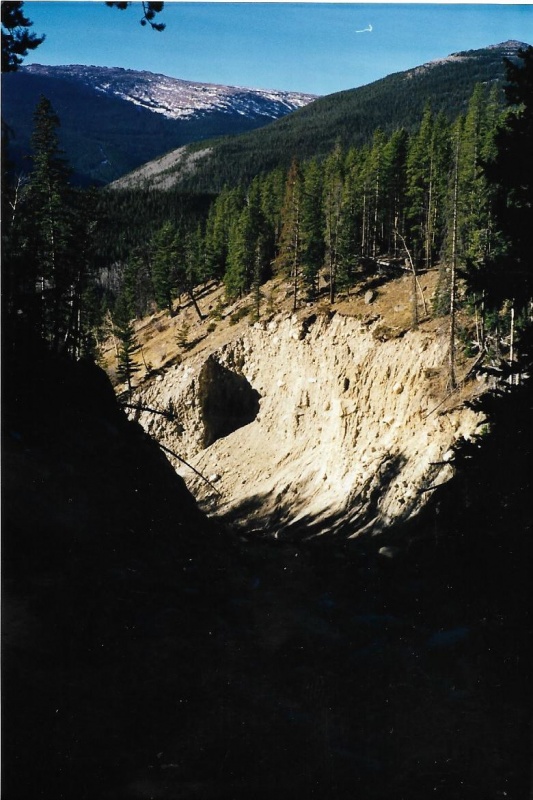

Since long before Rocky officially became a Park in 1915, farmers of the rich soils of the piedmont below the Front Range became dependent upon irrigation water that began as snowmelt high in these mountains above. The snowmelt flowed into streams that fed into and collected in natural, high mountain lakes. The lakes fed rivers, and the farmers had acquired legal water rights through productive agricultural use of the river water they themselves collected by building irrigation canals and ditches. The flow of this water was not constant through the growing season. It was a torrent in spring, but dried to a trickle or became nonexistent by fall. Farmers tried to make the river flow more constant by building dams and creating man-made reservoirs, or, as was the case at Lawn Lake, building a dam to increase the storage capacity and size of a natural lake. Then they managed a more constant flow of water by releasing controlled amounts through gateways and flumes. As time passed the dams got older and began to deteriorate. Many were not inspected or maintained properly. Leaks began, and once begun, they only enlarged through time. On what had started out as a fine, nondescript summer morning in July 1982, the Lawn Lake dam suddenly and catastrophically failed and gave way. A surge of violently churning water seethed over the exposed soil of the dam, eroding it and enlarging the immediate rupture even more. Thirty million cubic feet of water that had been contained by the dam only seconds before was released and sent plunging down the Roaring River canyon. At that moment, the river did truly roar. Very loudly. That early morning, a trash collector working down below and outside his truck was the first to hear that terrible roar, recognized it for what it was, and somehow made it to a telephone he could use. He called authorities, and explained as quickly as he could that he thought the Lawn Lake dam had just failed, and that Park Rangers, police, firemen, and all available first responders needed to take action immediately. That quick phone call undoubtedly saved many lives. First responders tried to warn and get everyone out of the way of the flood as fast as they could. There were a lot of people to warn. Most of the town of Estes Park, which had grown and developed around the intersection of the Big Thompson and Fall Rivers, was at risk, and in the path of the flood. The flood would first inundate Horseshoe Park in Rocky, enter the Fall River drainage, and only then reach the main streets of Estes, joining the Big Thompson. Those who knew that all that water would eventually end up in Lake Estes wondered if the lake’s huge concrete Olympus Dam would be able to hold up under the resultant sudden strain. They began releasing water from Lake Estes to get ready, and prayed the dam would hold. First responders took their jobs that day very seriously. Estes Park was no stranger to floods. Just a few years before, in 1976, on the last day in July, a massive, stationary thundercloud had dumped over twelve inches of rain in four hours on already rain-soaked mountainsides surrounding the Big Thompson and its North Fork, mostly below Estes Park. Most of that sudden rain ran off the mountains and into the Big Thompson. Then, similar runoff from the North Fork joined that in the Big Thompson. Early after midnight on the first morning of August, a wall of water nearly three times as tall as a big man swept down the narrow canyon below. Nothing could stop it. The water was powerful enough to lift houses off their foundations and crumple them. It tumbled rocks bigger than refrigerators along with the current, swept cars with people inside them from the highway. It tore through campgrounds. It ripped bridges from their pilings and destroyed large sections of the highway itself. Along its way, it drowned and killed over 140 people. Bodies of some of the missing were never recovered, and presumed to be buried too deeply to ever find. Only a few small bits and pieces of an entire ambulance that had raced into the canyon to try to help were ever found. Yes, first responders took their jobs that day in 1982 very seriously. This time, because of the early warning, only three people were killed by the Lawn Lake flood in 1982. The first was killed at a backcountry campsite along the Roaring Fork River midway down its canyon. That morning, he had slept in a bit, and the flood caught him still in his sleeping bag. The few others unlucky enough to be in the camp that morning had risen earlier. Already up and dressed, with their boots on, they had first heard the roar, and then had suddenly seen the deep water surging rapidly toward them. They were given the gift of maybe a split second to decide, and they made the right decision. They abandoned their gear, and instantly turned and quickly ran for their lives uphill, anywhere uphill, each alone and terrified, to try to get higher than the oncoming water before it hit them. They all made it. They lived. The other two campers killed had already evacuated the Aspenglen Campground near Fall River. Maybe thinking the evacuation was a false alarm, they had gone back into the campground to try to recover their gear. They didn’t make it back out alive. Much of the village of Estes Park was then flooded. There was extensive damage, especially to businesses along the main streets and homes that had been built too close to the river. Floodwater eventually reached Lake Estes, and swelled its level even more than expected. But Olympus Dam held, luckily, and no one else was killed. So that was the Lawn Lake flood. And the flood was amply evident throughout the entire length of the Roaring Fork valley as I hiked up it from the beginning of my Mummy Mountain climb, steadily gaining elevation. My photographs should tell the story.What can I say that can add to the photos? It is a long hike up a deeply eroded and damaged canyon.You gain a great respect for the forces of nature, and your own relative insignificance, when you hike this canyon. And you think, the whole time, about the three people who died here, and also about the people who must have cared for them and mourned their loss.

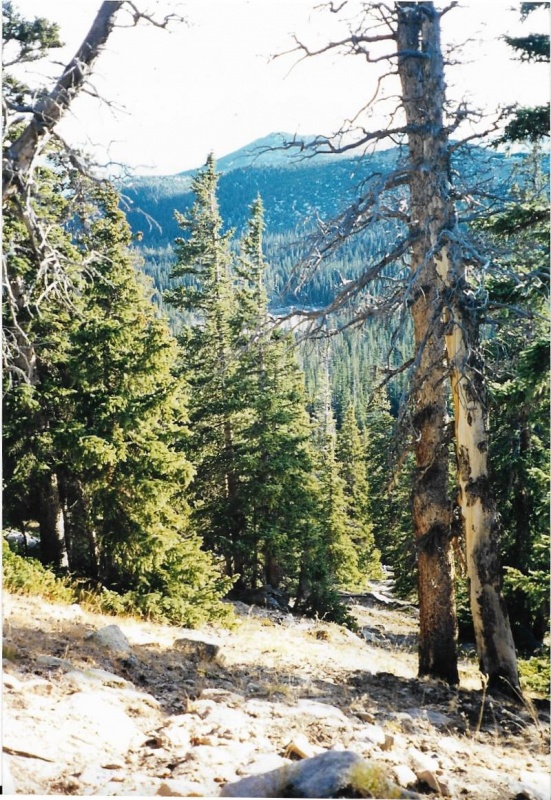

So. As I hiked up the flood-damaged canyon, I gained elevation, and pine forests eventually yielded to fir and spruce. The Montane Zone ended, Sub-Alpine began.

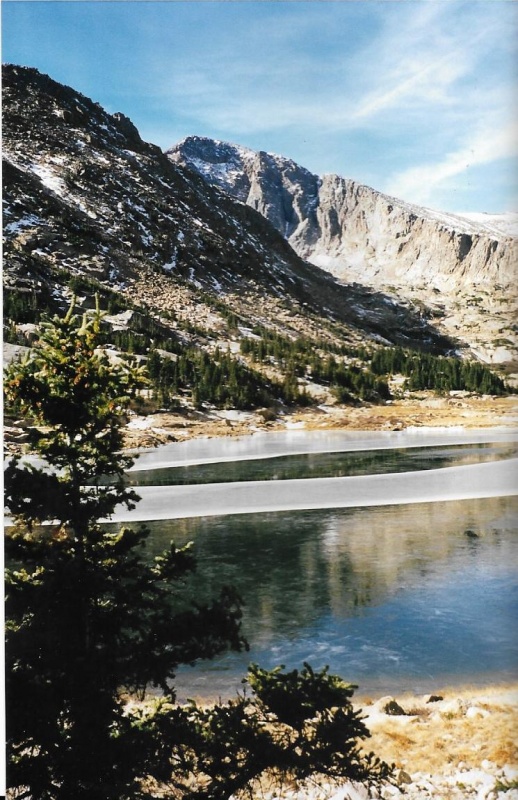

Before tree line, I came to the Black Canyon trail. Instead of turning onto it, I decided to hike on up to Lawn Lake and take a good look at it, and snap some photos. I did.

The lake was still open, but skimmed with ice in places.

The "Saddle," from which I would later climb Fairchild, Hagues, Rowe Peak and Rowe Mountain is right above the lake.

I took my photos, turned around, and hiked back to the Black Canyon turnoff, and turned onto it. I passed its high point, and began to descend. I wondered when that southeast ridge would lose enough elevation that it would be easy to ascend. I caught glimpses of it through the trees, and tried to judge.

I really don’t remember where exactly I decided to bushwhack through the trees and finally engage the ridge and begin the climb. One photo offers a clue, and a landmark. I know it is below both Tileston Meadows backcountry campsites, because I remember seeing them both. I wanted to look at them. Or perhaps I did that on a completely different hike than this one. The Black Canyon trail is long, without anything of real interest. It is a trail through a lengthy wooded valley best traveled fast as you can go on horseback. The place I chose to bushwhack, I think, was just below a rock formation that resembles a lion lying down, paws stretched ahead, with his head raised. I call it the Lying Lion.

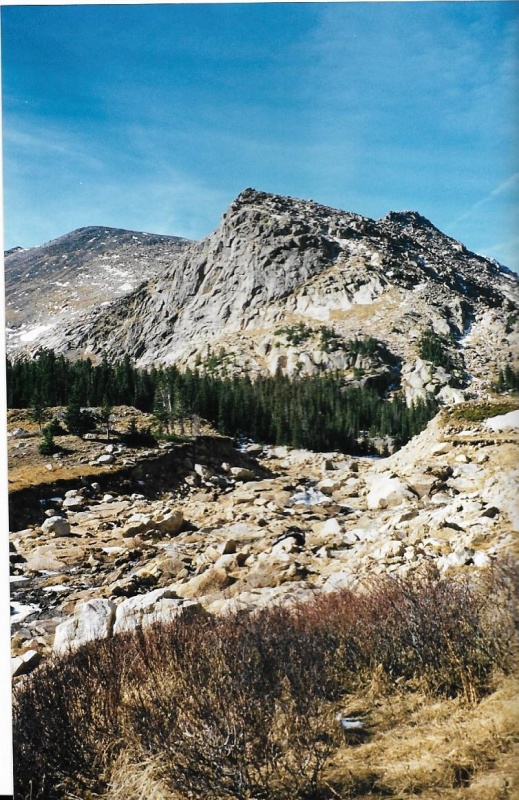

While I was still in the timber below the ridge, I picked up a stout stick I thought might serve as a trekking pole.I hadn’t yet bought a pair of collapsible trekking poles, but soon would do so. I engaged and gained the ridgeline probably just below the Lying Lion rock, because my note on the photo says to “hike behind this formation,” in other words, on the gentle tundra slope I found behind. Once I had gained the ridge, I climbed up the gentle tundra slope, passing behind the Lying Lion rock.

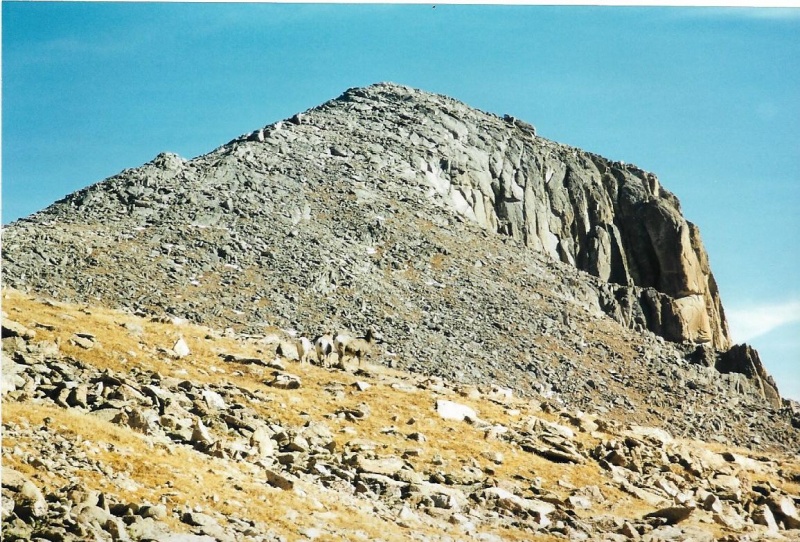

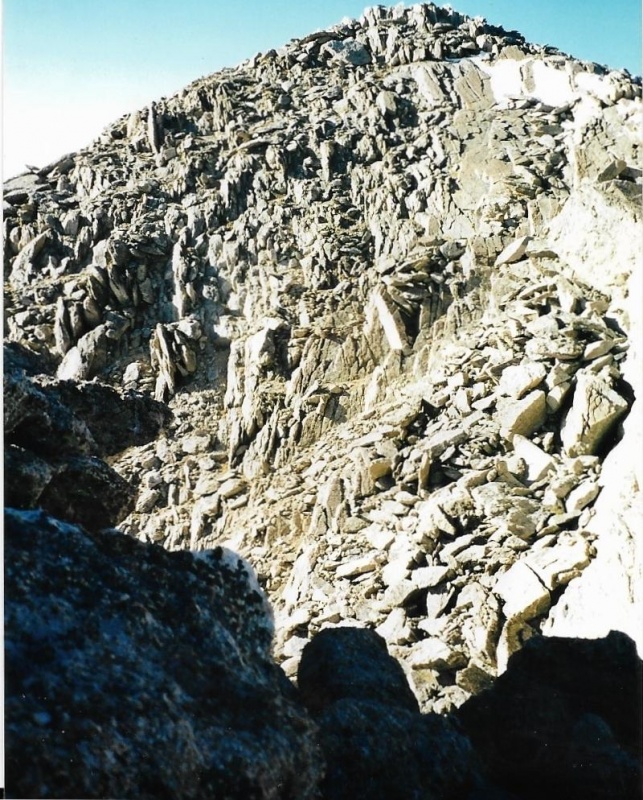

It was dropped there by a retreating glacier. The formal name for this is an "erratic." Up ahead, I could see the final summit pyramid of Mummy Mountain. The summit itself wasn’t grassy. It was rocky. Right before the summit was a gentle saddle, which connected the rocky pyramid and the ridgeline. When I got there, I photographed some bighorn sheep grazing in the saddle.They slowly moved off a bit when I passed them, but weren’t alarmed.

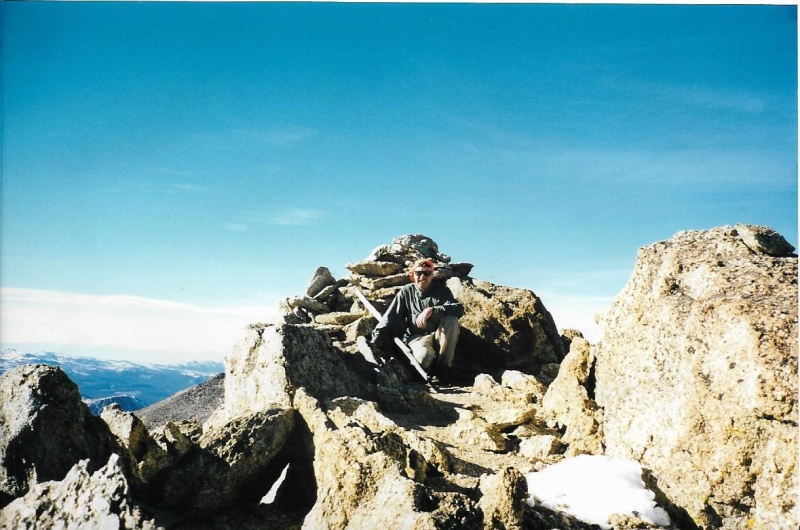

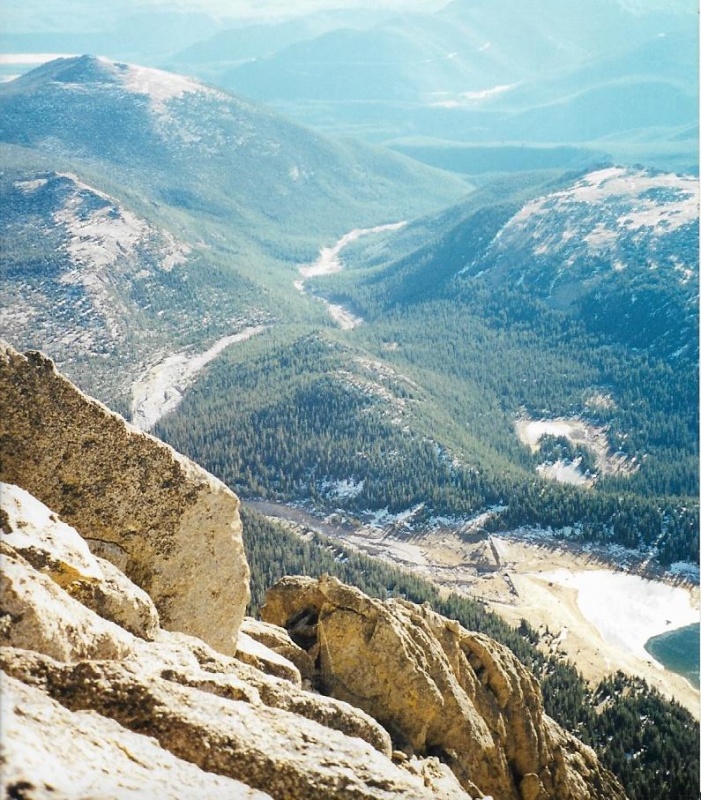

To the northeast, I could see a long way out over the flat plains that stretched out below the lower mountains.  My final push to the summit up the rocky slope was not difficult, and went quickly.  I found a small wind shelter of rocks on the summit, and a register. Using the automatic shutter timer of the small 35mm camera I carried, I sat it on rocks, and it took a few photos of myself alone on the summit, with my make-shift trekking pole.   I ate an energy bar and drank some electrolyte fluid, then some water, from my bottles.  I took a few photos of Lawn Lake with its failed dam far below. It had been a long hike, and I knew I was going to have to cover all that distance again on the way down, so I did not linger. I took a few more photos as I descended. This time I hiked closer to the ridge which drops off to the Roaring River valley below. The views were more dramatic from there.   I snapped a photo of Hague's and Rowe Peaks to the west. I hoped I would come back to climb them, as well as Rowe Mountain, sometime in the next year or two.  I think I must have passed the place where I had originally gained the ridgeline, because this time I encountered a trail that did seem to head down to the Black Canyon trail, but seemed to be heading straight down too far to the southeast to be suitable for my purposes.  I did not want to head toward the McGraw Ranch. I wanted to head toward Lawn Lake, so once again I bushwhacked through the trees below until I intersected the main, Black Canyon trail. Then I headed uphill toward its intersection with the Lawn Lake trail, retracing the path of my bootsteps that morning. I turned left onto the Lawn Lake trail, and started losing elevation toward the trailhead and the parking lot below. I knew I had been lucky. Indian Summer had held into November and I had been able to climb my second Park 13er! With that second success in 1999, I headed home, knowing I would begin climbing 13ers in earnest after snowmelt in the first summer of a new millennium! |

| Comments or Questions | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Caution: The information contained in this report may not be accurate and should not be the only resource used in preparation for your climb. Failure to have the necessary experience, physical conditioning, supplies or equipment can result in injury or death. 14ers.com and the author(s) of this report provide no warranties, either express or implied, that the information provided is accurate or reliable. By using the information provided, you agree to indemnify and hold harmless 14ers.com and the report author(s) with respect to any claims and demands against them, including any attorney fees and expenses. Please read the 14ers.com Safety and Disclaimer pages for more information.

Please respect private property: 14ers.com supports the rights of private landowners to determine how and by whom their land will be used. In Colorado, it is your responsibility to determine if land is private and to obtain the appropriate permission before entering the property.