| Report Type | Full |

| Peak(s) |

Mt Rainier - 14410 |

| Date Posted | 03/31/2015 |

| Date Climbed | 07/12/2014 |

| Author | MonGoose |

| Additional Members | RyGuy, GregMiller |

| Mt Rainier - Sea to Summit |

|---|

|

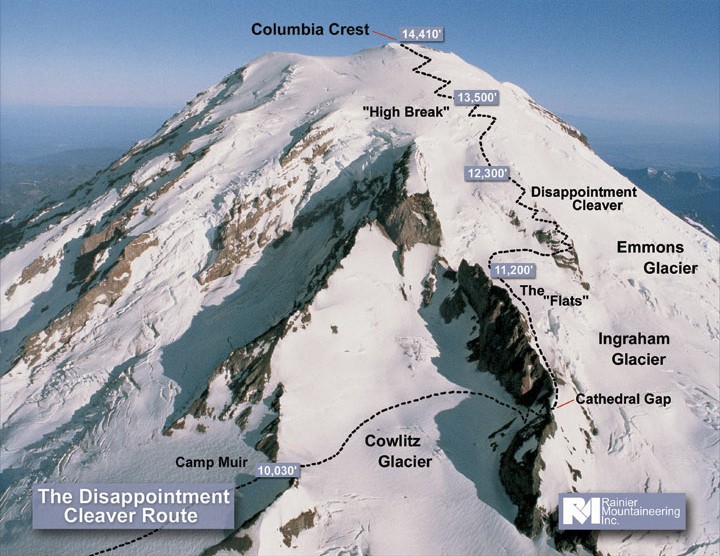

Mountain: Mt Rainier, Columbia Crest 14,410' Route: Disappointment Cleaver (7/11-13/2014) Day 1: Paradise to Camp Muir 6am to noon, rest in camp, leave for summit at 11pm Day 2: Climb overnight and summit at sunrise, return to Camp Muir Day 3: Descend from Camp Muir to Paradise RT Elevation: ~9,000' RT Distance: ~14 miles Preface: Life at Sea 2006-2007NOAA Ship Rainier S221 In January of 2006, I accepted a job with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to work as a Hydrographic Survey Technician mapping the ocean floor. I was assigned to NOAA Ship Rainier - a ship named after a mountain that towered over the land and the sea. The ship was stationed in Seattle, WA for the winter months until we would sail in the spring up the coast of Alaska to survey for the summer before returning once again to Seattle in the fall. I served for two field seasons on NOAA Ship Rainier working off the coast of Washington state and Alaska, and experienced many adventures along the way.  Working out in Puget Sound and looking up at the mountain, whose name we donned, was a great source of pride. It was here I developed dreams of climbing Mt Rainier as I routinely watched the evening alpenglow on the mountain. I began to research what it would take to accomplish such a feat but despite my burning desire, a few problems stood in my way: 1) I lived at sea level. It's hard to get acclimated while living on the ocean. 2) I wasn't in climbing shape. You don't get a lot of exercise, especially hiking, when you live on a boat year round. 3) We sailed to Alaska for the summer months, which meant I would have to fly back to Seattle to make the trip. I soon accepted the fact that climbing Mount Rainier was out of reach but I never gave up on the dream that one day I would stand on top of the mountain and look out to my ship at sea.  Life as a sailor was one never ending adventure but sailing for 200+ days a year began to take its toll. The field season in Alaska is short and as a result we were always sailing further north when the weather got nice in the spring. Then in the fall when the weather began to deteriorate, we would work our way back down to Seattle. Despite two field seasons consisting of many great survey areas, I was ready to return to land permanently. I accepted a job with the U.S. Geological Survey and moved to Denver, CO.  Rocky Mountain High, Colorado 2007 - presentShortly after moving to Denver, I climbed my very first mountain - Mt Bierstadt (14,060'). Over the next few years I continued to climb 14ers and I set my sights on completing the coveted list of 58, which I managed to accomplish in September of 2013. As I neared completion of Colorado's 14ers, the thought of Mt Rainier crept back into my mind. The three limitations I had faced in Seattle were no longer an issue. I was also adjusted to elevation and had climbed 3 Colorado peaks that were actually higher than Rainier. Originally I had planned to take a guided trip but I knew it would be a bigger challenge to go unguided. The only hurdle that remained was acquiring the necessary skills for glacier travel and assembling a strong team of climbing partners. I thought about all the friends I had climbed with in Colorado over the years and found two men with similar skill sets who were up for the challenge. The Three Amigos Ryan Richardson (aka RyGuy) Ryan is a nerd, there's no question about it. He's an IT guy with a love for gadgetry and is always playing with some new technology. Ryan is a problem solver. He has an app on his phone for every single problem imaginable. One evening while camping at 12,600' on Mt Sherman in a January snowstorm, we got into a discussion about hearing loss as men age. Ryan pulled out his phone and tried to give me a hearing test by playing a number of annoying tones at various frequencies on his phone. Another time on Atlantic Peak, a Colorado Centennial, I voiced my concern about a dark cloud that was quickly moving toward the summit at 9:30am on late June morning. Ryan pulled out his phone and got an instant weather forecast with a doplar radar for our location and commented where that storm was heading, just south of us. "I wouldn't want to be in that direction, something fierce is building". That evening I watched as the local news reported a tornado had touched down near the town of Fairplay in the direction where Ryan had pointed. Riding in Ryan's jeep is a cultural experience. His playlist consists of a mix of movie soundtracks and every song ever recorded by Daft Punk. When it comes to climbing, he likes to bring stuff... and by stuff, I mean frickin' everything. His nickname back home is "kitchen sink" because, well... he has every accessory known to western civilzation. He's prepared, no over prepared for any situation that arises. Ryan is the last boy scout and a grown up Eagle Scout. He continuously earns the merit badge for the heaviest pack. However, whatever problem you manage to get yourself into, Ryan will find a way to get out of it. He's also a chatter box and will talk with you about any subject for extended amounts of time. In addition, he's a very caring person with a big heart and healthy dose of confidence. I've never seen him angry at another person, only himself when he gets frustrated while setting up a 3-to-1 z-pulley system. But we've worked through that over these past 3 months. He has deep christian beliefs that he doesn't spring on others and won't even bring up unless asked directly. Sometimes I need to talk through my problems. With Ryan, I usually solve them twice and then find new ones before the conversation ends. Ryan lived in Bellingham, WA during the same time I was on NOAA Ship Rainier and had similar thoughts of climbing the mountain. After a failed attempt on the mountain last year, he's ready for redemption.  Greg Miller (aka GregMiller) Greg's personality is often the exact opposite of Ryan's. He's quiet, introspective, humble and extremely loyal. He despises loud music, attention whores like myself and just about anything that draws attention to himself (including this paragraph). When asked to pick a username for this website he chose: GregMiller. How's that for creativity? It will come as no surprise that Greg is an engineer as well as a technical climber. Unlike Ryan, who deserves every ounce of crap that I give him, I tend to go easy on Greg because he's such a nice guy. He brought us to the Southern Sun brewery on a week night to practice tying knots with parachute cord which Ryan and I hadn't fully grasped during our one-day training course. Greg's bright red hair and goatee coupled with a genuine smile give him a unique look that blends well with a healthy dose of sarcasm. I've always believed that gingers are good luck. He likes bluegrass and a healthy dose of the Lumineers. He's less concerned about lists and checkboxes and instead focuses his time on improving his skills. Everything he does, he takes the time to do correctly. He weighs every decision carefully and when he speaks up, it's because he has something meaningful to say. I remind myself to ask his opinion more frequently. Greg has looked up at this mountain many times while traveling to and from his hometown in Fairbanks, Alaska. Like a true Alaskan, he's mentally prepared for anything. He takes life as it comes and has a very calming personality. I need that, especially in the middle of this trip when we learn that the Disappointment Cleaver (DC) route has been re-routed to the west making our ascent longer than anticipated. Greg comes from a family of climbers and a brother who has successfully summited Denali. This trip is a right of passage for him and I want him to reach the summit as much as I do.  Both of these men are two of my closest friends and we have spent many hours together exploring Colorado. They would do anything to help me in a bad situation. They would also be willing to put down there dreams to help someone else because they're not afraid to turn around if the need be. They're both humble, hard working, loyal and are the kind of guys you want to be tied to on a rope on a glacier full of crevasses. And then there's me. Somehow I managed to talk them guys into this crazy adventure.  Contact with NOAA Ship Rainier I contacted CDR Rick Brennan who was currently serving as the captain of NOAA Ship Rainier and told him of my plans to climb the mountain. I asked if he could send me a flag from the ship that I could take to the summit. He sent me a NOAA flag that had flown over Rainier and I aspired to take it to the summit. I packed the flag into my pack, hoping it would bring good weather and safe travels. Sailors are superstitious people and having a ship named after a mountain is a source of pride. Having a flag on the ship that had been on the summit would surely bring good luck. Preparation & Logistics for Mt RainierClimbing extensively in Colorado prepared us for Rainier's elevation, while climbing in the winter and spring seasons went a long way to prepare us for glacier travel. Technically, Colorado does not have any glaciers (sorry, St. Marys "Glacier" is just a snowfield) meaning there are no crevasses, the primary concern of glacier travel. In order to prepare for a Crevasse Rescue, we took a 1-day course through the Colorado Mountain School in Estes Park, although many other local classes are also offered. To hone our skills, we spent a few weekends at St Mary's Glacier and Loveland Pass practicing rope travel, testing out our gear and working on crevasse rescue skills. I found the following resources to be very helpful in preparing for Rainier. The book Glacier Mountaineering: An Illustrated Guide to Glacier Travel and Crevasse Rescue by Andy Tyson provided everything we needed to know (and more) about glacier travel. The book Mt Rainier: A Climbing Guide by Mike Gauthier contains all the details about the park, the routes and logistics for most climbs. I also recommend Cairn Mountain Company's map of Mt Rainier. The Park Service requires each individual to acquire an Individual Climbing Permit which are readily available and cost $45 during the 2014 season. The Park Service also requires permits to camp in the backcountry which can be harder to attain. If you know your dates and route ahead of time, it's not a bad idea to call the Longmire Wilderness Information Center (360-569-6650) and reserve your spots for a $20 fee. If your plans change, you can change permits but it's good to know that your permits are already reserved. Camp Muir will occasionally fill up during the busiest weekends in August but the rest of the year, permitting is not much of an issue. Although, I suspect the mountain will only become busier in the future. We called ahead and reservations for Camp Muir were already booked for our planned dates. Fortunately, the Park Service withholds 30% of the permits to be picked up on a first-come first-served basis available the day before you start your climb. This system protects the individual climbers like ourselves from having their permits snatched up in advance by guided groups. The few times a year when they do run out of permits, overflow spots are available on the Muir Snowfield as well as Ingraham Flats. Logistically flying into Seattle is straightforward and Southwest is the most economical choice offering two free bags. The only item we were not able to bring on the airplane was fuel for our stoves, which we purchased at one of the local REI's. We spent the night at the Paradise Inn, a nearly 100 year old hotel inside the park with a rich, historic feel. Although the hotel room was slightly larger than my tent, the location was ideal. The weather forecast for our trip was optimal with no chance of storms and unseasonably warm temperatures. Day 1: Paradise (5,400') to Camp Muir (10,080')When we arrived in Paradise the evening before our climb, the Henry M. Jackson Visitor Center was chaos as hordes of summer tourists mulled around taking photos of the mountain. By 6:00am the next morning, the walkway was empty as the three of us stood looking up at the mountain. Despite the late night partying of our hotel neighbors, the morning was quiet and calm. From the Visitor Center, the journey begins with a quote by John Muir etched into the stone staircase: "... the most luxuriant and the most extravagantly beautiful of all the alpine gardens I ever beheld in all my mountain-top wanderings." -John Muir, conservationist, 1889 The trail to Camp Muir begins with a maintained summer trail that wonders through the meadows, before fading out at the base of the Muir Snowfield.   The route felt very symbolic of the journey into the wilderness. Annually 1.5 million people visit the national park of which only 10,000 climbers attempt to summit the mountain. And just over 50% of those are successful. Hiking up the trail you'll see dozens of tourists wandering about with their cameras. Once you hit solid snow, the tourists fade but recreational hikers and skiers enjoy the Muir Snowfield. Camp Muir consists mostly of climbers attempting the summit with a few hikers camping for just an evening and skiers looking for mid-summer turns. The farther up the mountain you climb, the less people you see. Each step is farther from civilization, farther into the clutches of the mountain. I've always felt the best reason to go into the mountains was to get away from everything for a few hours or days or maybe even weeks and on Rainier, this journey is highlighted. Each step is deeper into the unknown.  As the path fades out around 7,200', the Muir Snowfield comes into view. The Muir Snowfield is very similar to Colorado's own St Marys Glacier, with the exception of being surrounded by active glaciers. We hiked the 4,500' of elevation in just under 6 hours with our 50 lb packs. While most climbers on Rainier travel with lighter loads, we had brought all the luxuries for our stay at Camp Muir. Our morning hike was uneventful and felt like a spring snow climb on a mellow slope with 4,500' of elevation gain. As we climbed, large avalanches thundered down the Nisqually Glacier to our left. It was an amazing feeling every time the mountain shook. We enjoyed the cool morning air because we knew the afternoon heat was on its way.   Our Route to Camp Muir Historic Camp Muir Camp Muir is a bustling tent city with constant turnover of climbers, guided groups and Park Rangers. When we arrived at Camp Muir we found a large dug out shelf for our tent that we stole from a group that was leaving. The midday sun was already blaring down and there was no wind. Temperatures in Camp Muir hovered in the low 60's. After setting up the tent and making lunch, we explored Camp Muir. There is a public shelter made out of stone that was built in 1921 and is open to the public. Some folks spend the night in the shelter but I wouldn't recommend it. The hut is crowded, noisy and often over packed. If all else fails, it's a great backup plan for the evening but I'd much rather sleep in a tent. There's also an actively staffed ranger cabin and another permanent structure for guided trips. And of course, the infamous Camp Muir public restrooms with a smell you won't soon forget. When you check in at the ranger station in Paradise, they give you "blue bags" to collect and pack out your own excrement. Since most people don't like carrying bags of feces around, the Camp Muir facilities provides the only place to relieve yourself free of attachment. During the day, the glaciers melt causing instability. Overnight as the temperatures drop, the glaciers freeze and stabilize. A typical start time from Camp Muir to the summit would be around 2am but due to the extremely warm temperatures we were experiencing, the Rangers and guides we talked with were advising an earlier start time. We climbed into our tent around 4:00 in the afternoon to get some sleep before our all night climb.  The Camp Muir Webcam The Camp Muir Weather Station Drugs, No Sex and Rock & RollRyan and Greg popped some melatonin, their secret weapon sleep hormone to help them snooze in the noisy, brightly lit environment of Camp Muir. It was hot, there was a lot of activity happening around camp as new groups of people were coming in waves. I had no trouble falling asleep but unfortunately, only slept for about an hour and a half. I lay in my tent wide awake for the rest of the afternoon listening to my tent mates snoring. I tried to convince my body it would need the rest for the night climb but after a nice nap, I was wide awake. By early evening, the tent felt like an opium den as my junky tent mates slept deeply with a euphoric high from the melatonin. As for myself, I was experiencing the tell-tale signs of classic insomnia, you know, the type you get on a warm sunny afternoon in a noisy, hot and crowded environment at altitude. I decided it was time to enter the gateway drug of melatonin. Surely this would be my fall into the dark underworld of addiction. I envisioned the junky I would become, shooting black tar heroin on the crowded streets of Tijuana begging for just one more hit. I popped the little yellow pill of melatonin and I waited to see how my body would react. Hours later, nothing had happened. I was still wide awake. I rested in my sleeping bag listening to music and trying not to notice my watch slowly counting towards our 10PM wake up time. I knew I was in for a very long night of climbing and I didn't want to think about it. When the time finally arrived, a fury of alarms went off as I watched as Greg and Ryan sit up from their sleeping bags and wipe the sleep from their eyes. "Maybe they won't feel well and we'll decide to try for tomorrow evening instead?", I thought to myself. Greg: "How'd you guys sleep". Ryan: "Man, I slept I great. I feel really good." Greg: "Me too, I feel rested. Nick?" Me: "Dammit, looks like we're going to climb Rainier tonight." Although I felt okay, I knew I was in trouble. In a few hours my body would be expecting to go to bed instead of an all night attempt of Mt Rainier. I explained the situation to Greg and Ryan. They both offered to postpone the climb for another night which was a very generous offer. I thought hard about it for a minute. Here we were 4,300' below Rainier's summit, with good weather and I had two healthy team mates. If we waited another night, who knows what might happen? I remembered reading the final chapter of Gauthier's book where he said even if you don't feel well, get out and hike a little bit to experience the mountain. I figured even if we only gained 1,000', it would help prepare us for the next attempt. "Okay", I said. "I'm willing to give it a shot but I'm going to bonk at some point." It was still warm outside from the afternoon heat as we threw on our crampons, harnesses, backpacks and roped up in the darkness. Ascending to the Summit - Whatever is in the Way, Is the WayThere are a few factors which go into determining the order of the members on a rope team, which include: weight of the climber, experience and skills in rope handling. I took the lead on the 3-person rope team because, in my opinion, I possess superior route finding skills. Greg and Ryan will tell they put me in the lead because 1) I'm the slowest member of the group and 2) the most expendable. We agree to disagree on this point. The one thing we can all agree on is that the lead man on the rope is the most likely to fall into a crevasse. Greg, having the most technical climbing experience and rope handling skills, was the anchor in the back. If we got into trouble, he would oversee the entire rescue operation of removing a climber (most likely me) from the crevasse. Ryan took the middle, which tests the patience of the individual through constantly being pulled forward, back and sometimes both directions at once. The challenge in rope travel is to move at a pace as a team, without adding additional slack in the rope or tugging at your partners. This was our chance to apply all the skills we had practiced over the past months.  As we left Camp Muir at 11pm, I wished longingly for our usual 4am Colorado start time. This was an entirely new experience for all of us. The climb started off slow as we made our way across the upper Cowlitz glacier towards Ingraham Flats. I noticed the giant boulders on top of the snow we were walking past and I kept looking upslope wondering if another was going to let loose at any moment. We were struggling to settle in as a group. Traversing the bowl, there was a fair amount of small up and down hills as Ryan, in the middle, was getting pulled in both directions. Ryan: Hey, find a consistent speed, will you? Me: I'm trying, it's hard. Greg: I think that's just how it's going to be. Ryan: He keeps varying his speed. Me: Ryan, You're just going to have to deal with it. Ryan mumbled something under his breath that I didn't need to hear. We had practiced going uphill and coming down but didn't really work on rolling terrain. We also did all of our training in the daylight. Here we were in the middle of the night trudging along in the darkness. As we made it to the base of Cathedral Gap, we stepped off the snow of the glacier onto the dirt and rocks to take in strands of rope. The volcanic dust had a strong sulfur smell as we started ascending the Class 2 talus with our crampons still attached. I felt a little bit guilty as I had always taken good care of my crampons by avoiding walking on rocks. Now we were just pushing upward into the darkness. As we reached the top of Cathedral Gap, we took a water break and glanced back at Camp Muir which had exploded with activity. The entire "tent city" had come alive as an army of headlamps was making its way towards us. We were definitely ahead of the pack but there was an overall sense of urgency. When we arrived at Ingraham Flats, a few more groups were joining the super highway that was the DC Route. A guided group of 6 people was coming out of Ingraham Flats and I pushed to stay ahead of them. We met at the intersection at the same time, the guide looked at my team of 3 and his team of 6 and said, "you go ahead". I'll admit, I was a little out of my element. We had practiced rope travel a handful of times in Colorado, but never in the dark and not in the rat race of varying groups comprised of different abilities. Just above Ingraham Flats, we came to the largest crevasse on the route over which the guides had placed a 6' ladder. A traffic jam was piling up as one group after another crossed in the darkness. We waited our turn. I walked up to the ladder and glanced down into the darkness of my very first crevasse. I looked back at Greg and Ryan who were holding their ice axes in position ready to save me from my imminent fall. I always said I trusted them, but I was about to demonstrate it. Walking across a ladder isn't that difficult but throw on some crampons, in the middle of the night with some ice, snow and a few dozen observers; and psychologically, it becomes a bit more challenging. I ventured halfway across the ladder and peered down into the abyss. I couldn't see the bottom from the light of my 130-lumen headlamp. I continued across the ladder and prepared for Ryan and Greg. One crevasse down, many more to go.  As we approached the Disappointment Cleaver (DC), the prominent feature on the route, we were stacked behind a number of other parties. We traversed the ledge below the Cleaver and began ascending. The Disappointment Cleaver is often characterized as the toughest and potentially the most dangerous part of the route consisting of steeper snow climbing intermixed with loose talus. We discovered our group was quite prepared for this section given our Colorado experience. Our speed, however, was limited by the number of groups in front of us. Occasionally groups would let us pass but it was sort of like "playing through" on a golf course, only to discover that the slow group you had been waiting on was simply waiting on a slower group ahead of them. As we made our way higher on the DC, the moon came out and we began to see some of our surroundings for the first time. The eerie glow of the mountain shined in the soft moonlight. We made our way to the top of the DC and took a break on a rock section where we were able to group up. Our petty rope team problems early on had resolved and we were starting to get the hang of everything. We shared a moment of celebration acknowledging that we were really climbing Mt Rainier. Now that we were a few hours out of Camp Muir, it was getting colder. Ryan and Greg inquired about my condition. "I've got some more in me", I said "but I'm not going to make any promises". I was starting to feel tired and we still had a lot of climbing to do. I informed my teammates that turning around at some point was a real option. Although I didn't think I would have to, I wanted to give myself the flexibility to do so. After the Cleaver, I continued on at a slow but steady pace. We were in the midst of an army marching towards the summit in the full moon light as we worked our way in and out of the guided groups. The guides themselves were respectful, accommodating and communicated well with us and we showed respect to them in return. Some guides were talkative while others were focused on their clients. A few groups had as many as 8 people on a rope team, which were moving like molasses. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw a flash of red, glinting in the faint moonlight. It appeared as though something was running across the rope of the group in front of us, almost like a ghost. I shouted to my teammates and pointed at the mysterious object. "I don't see anything", Ryan shouted. Was I hallucinating? "There it is!!!", I yelled. We flooded the illusive being with our headlamps and saw the unthinkable. A fox!?!?! What was a fox doing at 12,000' on a glacier? Stealing lunches, I suppose. I wondered how he handles crevasses or has he ever reached the summit? The fox continued on his way out of site into the moonlight. "You saw that, right?", I inquired of Ryan. "Yeah, I saw the fox". Good, I wasn't delirious, yet. As we continued on with our slow and steady pace, our strength at elevation became apparent. We were flying past other climbers like they were standing still, and many of them were. The guided groups were assessing their clients condition before determining who would be sent back and who would continue on for the summit. Above 13,000' the winds picked up, the temperature dropped and my eyes began to water. My lack of sleep was taking its toll and I had run out of energy. I signaled to my partners that we were taking our final break before the summit. The group stepped a few feet off the route and I put on my puffy jacket. It was cold now. We were so close to the summit but I didn't know if I had any energy left in me. I forced food into my mouth even though I didn't feel like eating and rested for a few moments. The winds increased and there was no place to hide from the brutal gusts. "Nick, we can't sit here much longer. We're losing too much heat. We need to keep moving!", yelled one of my teammates. He was right. I glanced around searching for any place to get out of the wind. Nothing. We were completely exposed. This was the moment when I most needed a break, but we were doing more damage than good. I glanced down at my watch and noticed that my altimeter had gone haywire. It read we were at 30,000'. Although that felt accurate, I knew we weren't in the Himalayas and that position was about 17,000' too high. I was exhausted and it was time to make a decision. "How are you guys doing?", I yelled over the winds. "Good, let's keep going", they responded. I knew we were less than 1,000' below the summit. Could I go for one more hour? I looked downslope at my partners, I was so proud of these guys. They were encouraging me each step of the way. I pulled the folded NOAA flag out of my backpack and held it in my hand. "I need you now, please be with me". After cutting the break short, we continued on towards the summit. It felt like driving down the highway in the middle of the night, just trying to keep my eyes open after a long day. The route kept weaving to the west as we crossed a few snow bridges. Small cracks appeared in the snow, almost like little shadows across the route. I focused on taking just a few steps at a time. I was pushing my limits and running on empty. In my exhaustion, I failed to notice the faint light of morning starting to appear in the east. I glanced to my left and saw something in the distance: Point Success at 14,158', one of the lower summits of Mt Rainier was nearly at eye level. We were really close now. As we approached the rocks overhead we veered right and someone from another group yelled out, "That's the crater!". We had arrived.  Upon reaching the edge of the crater, we untied from the rope. As we crossed the crater towards Columbia Crest, Mt Rainier's true summit, I became full of emotion. We had climbed 9,000' of elevation in less than 24 hours and I did it on 2 hours of sleep. I felt relieved. Our Route to the Summit The SummitIt all starts with a vision of yourself standing on the summit of a mountain. When you start the months of planning, preparation and training you put that dream into action. When you actually begin to climb the mountain, you realize the reality of the cold, the exhaustion and the uncertainty involved. By the time you reach the summit, you may be in a daze or even feel that you are in an alternate reality. This wasn't the summit you dreamed of, possibly for years, from the warmth of your living room. But this is the reality, because when you dreamed, you dreamed of something you knew nothing about. And at the moment when you reach the pinnacle of everything you've wanted to so badly, you take a picture, soak it all in for an hour and then climb down the mountain to return home; where you will dream another dream and start the process over.     Me: "I'm really proud of you guys. I couldn't have done it without you". Ryan: "Same here, chief." Greg: "We all did it together." Seattle's own, Jimi Hendrix.   As I looked out over Puget Sound, I thought about NOAA Ship Rainier and the many times I had admired this mountain. First as a sailor looking up at Mt Rainier and now, as a mountaineer looking down at the ocean 14,000 feet below. The view was more beautiful than I had imagined. I thought about the lonely days we had spent in the Gulf of Alaska as the rain fell for days straight and the gray sky touched the gray sea in an almost seamless over the horizon. It was hard. Then I thought about the hour I had just spent in the darkness and the cold searching for a few more steps of energy to make it to right here. That also felt difficult. Both have been incredible journeys.  I pulled out the flag from NOAA Ship Rainier that I had carried all the way to the summit and clipped it to my ice axe. It certainly had brought us good fortune. The ship, commissioned in 1968, spans five decades and the lives of thousands of people who have sailed. This if for all the deck hands, officers, engineers and scientists who have contributed to her beauty over these past five decades. We are bound by this ship that has brought our lives together. I know how difficult the rigors of life at sea can be and trust me, mountaineering isn't any easier.  "The NOAA flag which flies over all NOAA ships traces its origins to the Coast and Geodetic Survey ships. The symbol of a triangle represents the triangulation methodology of geodetic survey. The NOAA logo was added to the flag in 1970 when NOAA was formed. The seagull symbolizes the mission of NOAA representing life that exists and interacts within the areas of NOAA's primary concern: the sea, the land, the air and, more specifically, life's dependence on the interface of these elements." -Source  Rainier has an area of hot rocks on the summit where you can warm yourself. We sat down and enjoyed a nice warm and relaxing break. Ryan discovers steam is hot.  The DescentI felt energized by the summit experience: the celebration of climbers reaching the peak, the warm morning sunlight on my face and getting the break I desperately needed. After finally finding a warm spot to sit, eat and rest on the summit, my strength returned. After an hour enjoying this special place, it was time to descend. We roped up and began the 2.7 mile trek back to Camp Muir. I was very grateful to be hiking on the downhill and for the daylight to show us where we were heading.    The morning views were absolutely incredible and it felt like climbing an entirely different mountain. For the first time we could actually see where we were going. The terrain we had stumbled through and the small cracks we stumbled across were actually 80' deep crevasses.   The morning warmed quickly and the snow softened up. By the time we were descending Disappointment Cleaver it was getting pretty sloppy.   R & R: Camp MuirUpon returning to Camp Muir, I quickly cooked a Mountain House meal and then it was time for my favorite post climb activity: taking a nap. I'm not sure what my tent mates were doing, I really didn't care. I dropped straight into a deep stage of REM sleep. We all slept for a good part of the afternoon as I had no trouble staying asleep this time. I felt like a new person when I woke a few hours later. The Hibernating MonGoose  We could have hiked down the Muir Snowfield that evening which would have required us to find a hotel. Instead we chose to spend an extra night in Camp Muir and enjoy the mountain for the rest of the evening. We hiked up to Muir Rock overlooking the tent and explored Camp Muir, checking out every nook and cranny. It was a lot of fun that evening at camp as we were glowing from our morning ascent. New waves of climbers were coming into Camp Muir and when questions arose someone would say, "go talk to those guys, they summitted this morning". "Those guys" were us. Heading Home"If you play that Macklemore song one more time, I'm going to smash your stupid speaker." -Greg After a good nights rest and a lazy morning, we said goodbye to Camp Muir, packed up our gear and began the hike to Paradise via the Muir Snowfield.  Halfway down the snowfield we ran into some familiar faces from back home. Zach Smith, Lynn Hall (LynnKH) and Corey Babb (theVagabond) were on their way up the mountain. We gave them solid advice which ultimately lead to their successful climb the following morning. Then we hurried down the mountain so we could get our pictures on Facebook before they did.  The glissading was definitely the best part.     If your climb is successful, you'll visit the gift shop and buy just about everything that says "Mount Rainier" on it. I bought a replica benchmark, two coloring books for my nephews and a bunch of postcards. Analysis from a Colorado ClimberLiving in Colorado, we reside at a higher elevation than the folks in the Pacific Northwest and have easy access to our highest peaks which include three mountains that are taller than Mt. Rainier. Paradise (5,400') is roughly the same elevation as Denver and Camp Muir (10,080') is about the elevation of your typical CO 14er trailhead. There is absolutely no reason a Colorado climber should not be acclimated. When it comes to elevation, we hold an advantage over people who live in Washington State. One unique feature of Mt Rainier compared to Colorado 14ers is the vertical relief of the mountain. Starting from Paradise, the mountain towers 9,000' above the landscape, the result of a dormant volcano. Nowhere in Colorado can you find this type of relief. Mt Rainier and Mt Shasta in California are the only two 14ers with active glaciers that require rope travel. The greatest disadvantage of climbing in Colorado is our lack of glaciers. We practice crevasse rescue by jumping of off cornices and cliffs to stimulate crevasses. Glacier travel is truly a team effort so pick partners whose company you enjoy and level of risk you can tolerate. Unlike a Colorado 14er where you can turn around and head back to the car, turning around on a glacier means multiple members must go back. Since we only had 3 members of our group, any person having to turn back meant the entire group was going home. Despite all of our training and practice for this trip, we expected to be less prepared than the other groups on the DC route. We were surprised to discover that we were a lot more prepared than a good majority of people on this route, many of whom were engaging in their first mountain climbing experience. Lastly, I can't stress the importance of getting more than 2 hours of sleep during the ascent. Hopefully you'll rest better than I did on that hot and sunny afternoon and maybe you'll even get to enjoy at 2AM start. I think you'll be glad you did.  Concluding ThoughtsThank you for reading about our journey to Mount Rainier, the highest volcano and largest glaciated mountain in the contiguous U.S. It was a an experience of a lifetime and I hope it inspires you to pursue the dreams that you have always felt were out of reach. I also hope this trip report provides insight for others researching the Disappointment Cleaver route. If you have any questions, please feel free to ask. And if you happen to see some Colorado schmucks on a distant 14er, please say hello. I also want to say thank you to the great folks I served with on NOAA Ship Rainier during the 2006 and 2007 field seasons. I miss you guys and I love following your continuing adventures on social media. Keep up the good work. Sincerely, Nick Gianoutsos aka MonGoose Special thanks to Ryan Kushner, Bill Wood, Rob Miller, Jeff Golden and Sam Sala for their advice on this trip. Thank you to the folks at Black Diamond whose amazing customer service allowed me make a few last minute equipment adjustments before this trip. Your customer service is the best. |

| Comments or Questions | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Caution: The information contained in this report may not be accurate and should not be the only resource used in preparation for your climb. Failure to have the necessary experience, physical conditioning, supplies or equipment can result in injury or death. 14ers.com and the author(s) of this report provide no warranties, either express or implied, that the information provided is accurate or reliable. By using the information provided, you agree to indemnify and hold harmless 14ers.com and the report author(s) with respect to any claims and demands against them, including any attorney fees and expenses. Please read the 14ers.com Safety and Disclaimer pages for more information.

Please respect private property: 14ers.com supports the rights of private landowners to determine how and by whom their land will be used. In Colorado, it is your responsibility to determine if land is private and to obtain the appropriate permission before entering the property.